Autoimmune rheumatic diseases (AIRDs) are known for their systemic presentations and multi-organ involvement. Numerous infectious diseases, particularly mycobacterial, fungal and indolent bacterial infections endemic to specific geographic regions, present with varied signs and symptoms of multi-system involvement and can mimic AIRDs. Thus, differentiating infection from an AIRD is critical to resolve competing treatment approaches. This case report demonstrates the need for clinicians to actively look for, and rule out, infections in patients with systemic manifestations and/or suspected AIRD.

Case Presentation

A 23-year-old man presented to our clinic in India with a three-year history of numbness and paresthesia in both feet and his left forearm without any motor weakness; a 1.5-year history of intermittent, moderate-grade fever (101°F) associated with chills; symmetrical, additive, inflammatory polyarthritis involving both the large and small joints of his arms and legs; early morning stiffness of around 30 minutes’ duration; and a six-month history of recurrent episodes of reddish painful swelling of his ears, nose and periorbital region (see Figure 1).

On an outpatient basis, he was initially diagnosed with relapsing polychondritis on the basis of recurrent episodes of auricular chondritis; nasal chondritis; seronegative, non-erosive, inflammatory polyarthritis; and peripheral neuropathy, with a nerve conduction study suggestive of bilateral tibial nerve axonopathy. No erosions were detectable on hand X-rays; power Doppler ultrasound of his hands and wrists revealed synovial proliferation and vascularity, but no erosions.

The patient was prescribed low-dose glucocorticoids and methotrexate, to which he had partial response. Eventually, his symptoms worsened and fevers became more frequent. He was admitted for evaluation.

On admission, the patient reported a history of painful lumps in his left inguinal region; weight loss of around 8 kg in a year-and-a-half, with a loss of appetite; episodic, painful erythematous nodular lesions over his legs; and episodic redness and pain in his right scrotum.

Examination revealed tender nerve thickening involving the ulnar, common peroneal and right greater auricular nerves on both sides (see Figure 2), with loss of pain, touch and temperature sensations in the distribution of ulnar and common peroneal nerves on both sides, and an absent left supinator jerk, right knee jerk and left ankle jerk. Joint position sense was preserved.

He also had multiple hypopigmented, normoaesthetic macules over his neck, trunk and both upper arms (see Figures 3 & 4); tender inguinal lymphadenopathy (2 cm, firm, mobile); erythematous tender nodules over his left shin and left antecubital fossa suggestive of erythema nodosum; and a tender joint count of 36/68 and a swollen joint count of 4/66 in both his knees and ankles.

Differential diagnoses of lepromatous leprosy, tuberculosis, relapsing polychondritis and medium vessel vasculitis were entertained.

The patient’s complete blood count (CBC), RF, liver function, urine routine/microscopy (R/M), post-anterior chest X-ray, whole abdomen ultrasound and two-dimensional echocardiogram tests were within normal limits. He had raised inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein [CRP]: 5.32 mg/dL [upper limit of normal (ULN): 0.3] and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]: 49 mm/hour [ULN: 15]). Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody and anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) screening were negative. An infectious workup, consisting of blood culture, urine culture, viral markers and Mantoux tuberculin skin test, was negative.

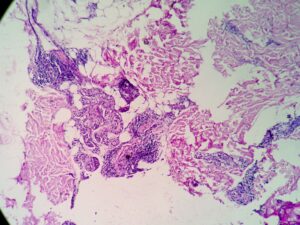

A skin biopsy of the hypopigmented macules revealed septal panniculitis without vasculitis (see Figure 5), but Fite-Faraco staining for acid fast organisms was negative, as was a slit skin smear from the ear lobule.

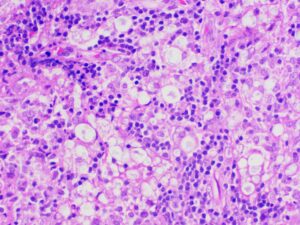

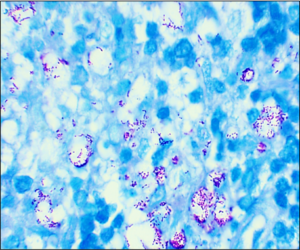

An inguinal ultrasound suggested necrotic inguinal lymph nodes, with excisional biopsy revealing collections of foamy histiocytes (i.e., lepra or Virchow cells) interspersed with lymphocytic infiltrates. Fite-Faraco staining highlighted globi of acid fast bacilli (Mycobacterium leprae) within and around the foamy histiocytes (see Figures 6 & 7). Lymph node cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test (CBNAAT) didn’t detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli, ruling out tuberculosis, which is a close differential of leprosy.

A diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy with type 2 lepra reaction was made, with components including neuritis/nerve thickening, normoaesthetic hypopigmented macules, erythema nodosum, inflammatory polyarthritis, cartilage inflammation, episodic orchitis and tender lymphadenopathy.

The patient was started on multidrug therapy for multi-bacillary leprosy (MDT-MB) because he had more than five skin lesions and more than one nerve thickening. MDT-MB comprises dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimine. The treatment duration was planned for one year. High-dose glucocorticoids (i.e., 1 mg/kg of prednisolone) for type 2 lepra reaction was also prescribed.

At one month follow-up, the patient had recurrence of erythema nodosum lesions and auricular and nasal chondritis due to rapid tapering of glucocorticoids, so prednisolone and clofazimine doses were increased and MDT-MB was continued. His symptoms completely resolved and didn’t recur on further follow-up visits.

Discussion

This case report describes a case of lepromatous leprosy masquerading as relapsing polychondritis.

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is a chronic granulomatous disease caused by M. leprae, which primarily affects the skin and peripheral nerves.1 However, it can affect nearly all organs and organ systems, with long-term complications and significant morbidity and mortality, thus requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment. Leprosy still occurs in over 120 countries but remains particularly endemic to Southeast Asia, with more than 10,000 cases reported in 2019 in each of India and Indonesia.2

Figure 6: Lymph node biopsy shows foamy macrophages interspersed with lymphocytic infiltrates (lepra or Virchow cells).

Autoimmune diseases are characterized by multi-system manifestations, so it is important to rule out chronic infections, such as tuberculosis, leprosy and fungal infections, because the treatments for infections and autoimmune diseases are opposing, with the latter requiring glucocorticoids and immunosuppression and the former requiring antibiotics (and worsening with immunosuppressants). Particularly given the low sensitivity of many diagnostic tests for indolent infections, a high level of suspicion is needed when environmental or occupational histories suggest a higher risk for certain infections.

Our case highlights the importance of looking for chronic infections, such as leprosy, as mimics of AIRDs, such as relapsing polychondritis in this particular scenario.

Complete ear involvement occurs in leprosy in the form of painless, infiltrative nodular lesions of the pinna, with characteristic involvement of the ear lobule because the M. leprae has a predilection for involvement of cooler body sites.3 However, our case presented as painful auricular chondritis, sparing the lobule, which is a characteristic feature of relapsing polychondritis, and leading to the initial incorrect diagnosis.

Tender lymphadenopathy, nerve thickening and skin lesions were oddities in our case, which hinted at leprosy, an age-old mimic of autoimmune disease. The skin biopsy revealed septal panniculitis without vasculitis, with negative Fite-Faraco staining and slit skin smear. Despite that, a high suspicion of leprosy remained. Hence, the tender inguinal lymph node was targeted, which revealed the foamy histiocytes and globi of M. leprae on Fite-Faraco staining, clinching the diagnosis.

Figure 7: Lymph node biopsy Fite-Faraco staining shows globi of M. leprae bacilli. (Click to enlarge.)

Skin biopsy and slit skin smear have a low sensitivity of around 49–70% and 50%, respectively, for a diagnosis of leprosy.4 Gupta et al. did a histopathological study of lymph nodes in 43 cases of leprosy and showed that lymph nodes, if present, can show M. leprae in 92.2% of cases.5 Thus, a clinician should try to get a tissue or microbiological diagnosis, which at times may require repeated attempts at tissue sampling, as in our case.

A thorough history and systemic examination are crucial even in the modern world of advanced diagnostics. Appropriate tissue biopsy should be targeted for definitive diagnosis. One should actively rule out infection before diagnosing an AIRD because the treatments are diametrically opposite.

Rohan Goel, MBBS, MD, is a resident at the Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research and Seth Sukhlal Karnani Memorial Hospital, Kolkata, India.

Rashmi Roongta, MBBS, MD, DM, is the senior resident at the Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research and Seth Sukhlal Karnani Memorial Hospital, Kolkata, India.

Dipendranath Ghosh, MBBS, MD, DM, is a rheumatologist at the Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research and Seth Sukhlal Karnani Memorial Hospital, Kolkata, India.

Parasar Ghosh, MD, DM, is a rheumatologist and head of the department of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research and Seth Sukhlal Karnani Memorial Hospital, Kolkata, India.

References

- Srivastav Y, Prajapati A, Jaiswal A, et al. Overview of leprosy, including the diagnosis and current available treatments. J Innov Appl Pharm. 2023 Oct;8(3):24–33.

- Leprosy [fact sheet]. World Health Organization. 2023 Jan. 27. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leprosy.

- Sharma A, Chattopadhyay A, Narang T, et al. Looking at the lobule-importance of ears and years in rheumatology. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Jan;60(1):477–478.

- Chen KH, Lin CY, Su SB, et al. Leprosy: A review of epidemiology, clinical diagnosis, and management. J Trop Med. 2022 Jul 4; 2022:8652062.

- Gupta JC, Panda PK, Shrivastava KK, et al. A histopathological study of lymph nodes in 43 cases of leprosy. Lepr India. 1978 Apr; 50(2):196–203.