Syphilis, an ancient disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, has been historically referred to as the great mimicker given its heterogenous presentation. Both systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and syphilis can have multi-systemic involvement. Both parvovirus B19 and syphilis have been reported to cause histologic features similar to those seen in lupus nephritis.

We present a case in which co-infection with syphilis and parvovirus B19 could have been mistaken for lupus nephritis. We highlight clinical features to help differentiate between lupus nephritis and nephrotic syndrome caused by co-infection with syphilis and parvovirus B19. Making the correct diagnosis has important implications: Nephrotic syndrome associated with parvovirus B19 often improves spontaneously and that with syphilis improves with penicillin, whereas lupus nephritis requires systemic immunosuppression.

Case Presentation

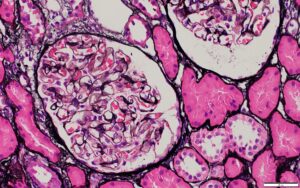

A 34-year-old Angolese man presented with lower extremity edema, headache, malaise, arthralgias, rash, diarrhea and chest pain of six weeks’ duration. He previously was evaluated at an urgent care clinic and was prescribed an oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug for chest pain and myalgias, with symptomatic improvement. Renal biopsy was concerning for classes II and V lupus nephritis, for which a rheumatologist was consulted.

His creatinine was 1.4 mg/dL (reference range [RR] 0.75–1.20 mg/dL for men) on admission. Liver function tests were normal, except for an isolated elevation in alkaline phosphatase confirmed to be of hepatic etiology, with a corresponding elevation in gamma-glutamyl transferase.

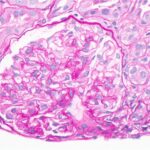

FIGURE 2: ELECTRON MICROSCOPY

Rare subepithelial and mesangial immune complex mediated type electron dense deposits present. Moderate podocyte epithelial foot process effacement is shown.

(Click to enlarge.)

The patient had recently been diagnosed with syphilis and treated with intramuscular penicillin a few weeks prior to his admission. His medical history included a prior diagnosis of COVID-19 and a remote history of malaria. Neither he nor his family had any history of autoimmune disease. He had not been taking any regular medications prior to admission. He denied use of illicit substances and had no travel outside the U.S. in several years. He reported being sexually active with male partners.

On admission to our hospital, his exam revealed prominent bilateral axillary and bilateral inguinal lymph nodes, soft tissue swelling in both ankles and pretibial pitting edema. Examination found no appreciable rashes on the skin, including a normal genital exam with no ulcerative lesions. The patient denied malar rash, photosensitivity, Raynaud’s phenomenon, history of venous thromboembolic events, dry mouth, dry eye, history of seizure or stroke, history of cytopenias, nasal or oral ulcers, or hair loss.

Initial urinalysis several weeks prior to admission showed 2–3+ protein, 2+ blood, and no casts. Proteinuria was quantified with random urine-to-protein-creatinine ratio, which was elevated at 5.65 g/g Cr. The ANA titer was 1:640 in nuclear coarse speckled pattern; tests for anti-Smith and double-stranded DNA antibodies were negative.

Serum complements were not low. A test for phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) antibody was negative. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antigen and antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody, and hepatitis C antibody were negative. A test for RPR was positive (1:256), with a positive confirmatory syphilis total antibody test. Chlamydia and gonorrhea polymerase chain reaction testing returned negative. Tests for anti-phospholipid antibodies were negative.

The complete blood count test with differential was normal. Ferritin (408 ng/mL; RR: 12–300 ng/mL for men) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (56 mm/Hr; RR: 0–15 mm/Hr) were elevated; C-reactive protein (CRP) was just above the upper limit of normal (0.6 mg/dL; RR: <0.5 mg/dL).

Liver function tests revealed hypoalbuminemia (1.9 g/dL) and elevated alkaline phosphatase (413 U/L; RR: <129 U/L) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (872 U/L; RR: <61 U/L). Serum parvovirus B19 IgG (1.16 IV; RR: <0.90 IV) and IgM (1.97 IV; RR: <0.90 IV) were consistent with recently acquired infection.

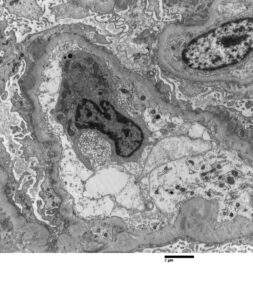

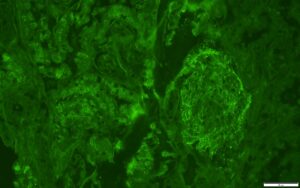

A renal biopsy was suggestive of classes II and V lupus nephritis; however, no crescents were identified (see Figure 1, opposite). Renal biopsy showed a combined (segmental) membranous and minimal mesangial pattern of glomerulonephritis with negative PLA2R antibody stain (see Figure 2, opposite). On immunofluorescence, glomeruli showed segmental, capillary loop and full-house pattern (positive for IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q) co-staining (see Figures 3 and 4, this page). Spirochete stain was negative on immunohistochemistry.

Given the presence of persistent headache, along with neck tenderness and positive syphilis testing, a lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis was performed, which revealed normal cell count, negative gram stain, normal glucose and negative venereal disease research laboratory test.

Patient presented with nephrotic syndrome (i.e., nephrotic range: proteinuria, elevated cholesterol and edema), which improved during his hospitalization. He was treated with 30 mg of lisinopril daily and 40 mg of atorvastatin daily.

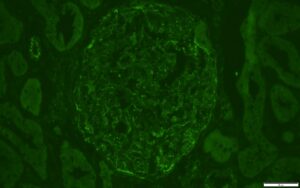

FIGURE 3: IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE IgG STAIN

IgG stain is positive in a granular pattern along capillary loop and rare mesangial areas.

(Click to enlarge.)

At his one-month outpatient follow-

up, his edema, headache, arthralgias, malaise, rash and diarrhea had all resolved. His cholesterol had normalized with statin therapy. Repeat urinalysis showed no blood and no protein, and the random urine-to-protein-creatine ratio had completely normalized (0.08 g/g Cr). His serum creatine declined to 1.2 mg/dL. His inflammatory markers had also completely normalized (ESR 1 and CRP <0.5 mg/dL), as had his alkaline phosphatase and albumin.

Discussion

Searching PubMed, we identified only one case of co-infection with syphilis and parvovirus B19 mimicking lupus nephropathy, as in our patient.1 Parvovirus B19 and especially syphilis have been reported to cause the same histologic features of lupus nephritis—or so-called pseudo-lupus nephritis. Although the presence of C1q deposits is nearly pathognomonic for lupus nephritis, it can also be seen when parvovirus B19 causes kidney disease.1

Our patient’s positive ANA and full-house pattern on renal biopsy pointed toward lupus nephritis; however, the discordant findings of negative double-stranded DNA and anti-Smith antibodies, lack of cytopenias, normal complements and lack of other clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus made us question the diagnosis.

Syphilis fit the clinical schema well—and it should be noted that our patient’s mild hepatitis, with isolated elevation of alkaline phosphatase, is very characteristic of syphilitic hepatitis.2 The presence of C1q deposition in the kidney prompted us to check for parvovirus B19 antibodies, which came back suggestive of acute infection. This likely explained his symptoms of malaise and arthralgias, as well as skin redness/rash (which was not appreciated on admission when we evaluated the patient, several weeks after symptom onset). Other masqueraders of lupus nephritis include HIV and infective endocarditis.

Syphilis has been historically referred to as the great mimicker given its heterogenous presentation.3,4 The three stages of infection are: primary, secondary and tertiary. Our patient likely had secondary infection, with rash and lymphadenopathy. Renal involvement can occur at any stage, from secondary to latent and tertiary. Both SLE and syphilis can have multi-system involvement.

FIGURE 4: IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE C1Q STAIN

Trace staining also noted for C1q in similar distribution as IgG stain.

(Click to enlarge.)

This case illustrates the importance of thinking about infectious etiologies for glomerulonephritis and completing a thorough sexual history. Further, the diagnosis of lupus nephritis should be questioned when serologic and other laboratory markers (e.g., anti-Smith and double-stranded DNA antibodies, low complement levels, cytopenias) and clinical manifestations of lupus are absent, despite suggestive renal histology findings. The presence of C1q is nearly pathognomonic for lupus nephritis, but can also be seen when parvovirus B19 causes kidney disease.1 Parvovirus B19 and syphilis have been reported to cause the same histologic features of lupus nephritis. 1,3,4-6

In Sum

It’s important to recognize the above etiologies of membranous nephropathy because the correct diagnosis has treatment implications. The nephrotic syndrome associated with parvovirus B19 infection may improve spontaneously and that with syphilis improves with penicillin.3,5-7 A similar case of co-infection with both parvovirus B19 and syphilis improved with antibiotic treatment for syphilis.1

Matthew J. Mandell, DO, is a staff rheumatologist at Cleveland Clinic. He completed his rheumatology fellowship training at the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics, Iowa City.

Yishui Chen, MD, is a second-year neurology resident at the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics.

Prerna Rastogi, MD, PhD,is clinical associate professor of pathology and medical director of electron microscopy and outlying urgent care and hematology/oncology laboratories at the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics.

Rebecca Tuetken, MD, PhD, is a clinical professor of internal medicine (immunology), medical director of the Medical Specialty Clinic, and director of the rheumatology fellowship program at the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics.

References

- Jaunin E, Kissling S, Rotman S, et al. Syphilis and parvovirus B19 co-infection imitating a lupus nephropathy: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Sep;98(36):e17040.

- Young MF, Sanowski RA, Manne RA. Syphilitic hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992 Sep;15(2):174–6.

- Scaperotti MM, Kwon D, Kallakury BV, Steen V. Not all that is ‘full house’ is systemic lupus erythematosus: A case of membranous nephropathy due to syphilis infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 Aug 19;14(8):e244466.

- Hook EW 3rd. Syphilis. Lancet. 2017 Apr 15;389(10078):1550–1557. Erratum in: Lancet. 2019 Mar 9;393(10175):986.

- Georges E, Rihova Z, Cmejla R, et al. Parvovirus B19 induced lupus-like syndrome with nephritis. Acta Clin Belg. 2016 Dec;71(6):423–425.

- Hannawi B, Raghavan R. Syphilis and kidney disease: A case report and review of literature. Nephrology Research & Reviews. 2012;4(2):45–47.

- Ohtomo Y, Kawamura R, Kaneko K, et al. Nephrotic syndrome associated with human parvovirus B19 infection. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003 Mar;18(3):280–282.