Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a primary, necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis, involving small- to medium-sized arteries, that causes systemic disease. Almost any organ can be affected, but the most affected systems are the upper airways, lungs, kidneys, eyes and peripheral nerves. Migratory polyarthritis is reported in approximately 25% of patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis (AAV); however, it’s rarely reported as the initial presenting symptom.1,2

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a primary, necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis, involving small- to medium-sized arteries, that causes systemic disease. Almost any organ can be affected, but the most affected systems are the upper airways, lungs, kidneys, eyes and peripheral nerves. Migratory polyarthritis is reported in approximately 25% of patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis (AAV); however, it’s rarely reported as the initial presenting symptom.1,2

Here, we present a case of GPA with migratory polyarthritis as the initial manifestation.

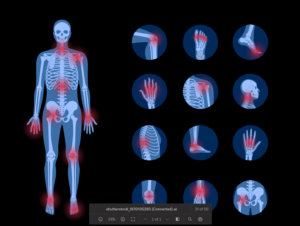

History of present illness: A 49-year-old man without significant medical history presented to the rheumatology clinic for evaluation of polyarthritis that had started eight months before. He reported three episodes of migratory polyarthritis, involving different joints each time (i.e., shoulders; elbows and wrists; knees, and ankles). During each episode, he noted joint swelling, redness (see Figures 1A and 1B), stiffness and pain; his symptoms lasted for five days and then resolved after he received a course of glucocorticoids.

During the second flare, he experienced redness, pain and floaters in both eyes, which also improved with glucocorticoids. He was subsequently seen by an ophthalmologist, who diagnosed him with bilateral iritis.

Additionally, he described chronic low back pain that worsened with exercise and prolonged morning stiffness that he’d experienced for a few years.

Three weeks before his rheumatology visit, he visited the emergency department for evaluation during an inflammatory flare. Plain X-ray films of his ankles showed mild to moderate soft tissue swelling without evidence of acute fracture or osseous abnormalities.

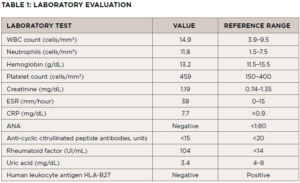

Laboratory tests are summarized in Table 1.

He was discharged on a glucocorticoid regimen and was referred to a rheumatology clinic.

Past medical history & medications: The patient had no pertinent, previous medical history or surgery. The patient’s medications were 10 mg of prednisone daily and 800 mg of ibuprofen twice daily as needed. He denied any recent antibiotic or other medication use, herbal use or vaccination.

Social & family history: He reported no family history of psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or other autoimmune conditions. He has been smoking one pack per day for 10 years. He consumes alcohol socially and denies using any recreational drugs, such as cocaine or heroin. He has lived in Ohio with the same female partner for many years, with no recent travel.

Review of systems: He reported migratory polyarthritis, recent ocular pain and redness, and chronic low back pain and stiffness. The patient denied any skin rash, such as psoriasis; constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, weight loss and night sweats; dactylitis; gastrointestinal or genitourinary symptoms; nasal discharge, crusting or bleeding; nasal or auricular chondritis; sinus or respiratory symptoms, such as cough, hemoptysis or shortness of breath; sore throat; numbness or tingling sensation in his extremities; recent infection, including sexually transmitted disease; or tick bite preceding his symptoms.

Physical examination & laboratory evaluation: Upon evaluation, the patient was afebrile (98ºF), had a blood pressure of 123/83 mmHg, a heart rate of 90 beats per minute and a normal respiratory rate.

He was well appearing and not in acute distress. He had clear sclera, without focal sinus tenderness, nasal crusting or deformity. His skin examination was normal, without evidence of psoriasis, nodules or purpuric rash. The lung auscultation was clear. The patient didn’t have any pitting edema in his lower extremities.

The musculoskeletal examination revealed no active synovitis in his joints, except for focal tenderness in both ankles without apparent effusion, and a Schober’s test was limited (i.e., 10–13 cm), without focal tenderness over his sacroiliac joints or the rest of his spine.

Differential Diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for migratory polyarthritis includes palindromic rheumatism, infectious processes, such as Lyme disease and viral infections, spondyloarthropathy, sarcoidosis, connective tissue disorders and vasculitides and paraneoplastic polyarthritis.3

Palindromic rheumatism: A rare inflammatory arthritis, palindromic rheumatism is characterized by recurrent attacks, manifesting as joint pain and swelling without chronic joint damage. Episodes are self-limited, resolving within a few hours to days. Patients with anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies are at increased risk to progress into rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in up to 50% of cases.

Our patient presented with migratory polyarthritis without constitutional symptoms and had a positive rheumatoid factor (RF) test, which would put palindromic rheumatism high on the list of possible diagnoses. However, whereas episcleritis and scleritis are both reported in RA, a history of iritis is not usually a common symptom.4,5

Infectious causes: Viral and bacterial infections, such as parvovirus B19, may cause migratory polyarthritis by a reactive process. It may present as asymmetric oligoarthritis in children; in adults it tends to manifest as symmetrical polyarthritis.6 Hepatitis B can present prodromal symptoms, symmetrical polyarthritis and a positive RF test in up to 80% of cases.7

Alphavirus and chikungunya infections may manifest with fever associated with conjunctivitis and symmetrical polyarthritis involving small, medium and large joints with a relapsing and remising course, as in rheumatic fever and reactive arthritis.

Infections can cause direct joint infections as well, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Borrelia burgdorferi and Tropheryma whipplei infections, which can present early as asymmetrical, intermittent polyarthritis without gastrointestinal symptoms, then turn into a symmetrical polyarthritis, mimicking seronegative RA.8,9

Recognizing an infectious cause of migratory rheumatism is vital because the management differs from an autoimmune cause.

Spondyloarthropathy: The spondyloarthritides constitute a group of heterogeneous entities (e.g., psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, IBD-associated arthritis, ankylosing spondylarthritis) sharing common characteristics. Psoriatic arthritis and IBD-associated arthritis often present as asymmetric polyarthritis favoring lower extremity joints. However, our patient denied any personal or family history of psoriasis, Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

Reactive arthritis was high on the differential diagnosis for our patient because of his history of migratory polyarthritis and iritis, as well as his chronic low back pain, but given the lack of preceding infection, gastrointestinal and genitourinary symptoms, and the presence of RF, it was considered less likely.

Ankylosing spondylitis generally presents in young men with long-standing, chronic back pain and prolonged morning stiffness, peripheral polyarthritis and iritis, which were all present in our patient, but the presence of high-titer of RF made it less likely.

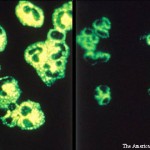

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) & other autoimmune conditions: Arthritis in SLE is a very common symptom and typically tends to be migratory, symmetric and non-erosive. It rarely causes joint deformity, but is associated with minor joint effusion, and usually affects the small joints of the fingers and knees.10 Our patient had no skin rash, photosensitive rash, pleuritis or other features to suggest SLE. In addition, anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) were absent, and patients with SLE rarely get uveitis.

Sarcoidosis: As a heterogeneous, multisystem granulomatous disease that primarily affects the lungs and lymphatic system, arthritis can be found in 15–25% of patients with sarcoidosis.11 Two major types of arthritis have been classically distinguished: acute transient, and persistent or chronic.11

The acute form is more frequent and often the presenting symptom of sarcoidosis. Uveitis, generally in both eyes, is a frequent (20–50%) and early feature of the disease.12

Sarcoidosis was also high in the differential diagnosis with the presence of acute arthritis and uveitis; further diagnostic evaluation, such as chest imaging, would be needed for further investigation.

Paraneoplastic polyarthritis: A rare entity that has been described most in adenocarcinomas of the lungs and breasts, and as a hematological malignancy, paraneoplastic polyarthritis is characterized by migratory polyarthritis affecting primarily joints in the lower extremities, with the presence of RF and ANA in rare cases (20%).

Our patient was relatively young and had no constitutional symptoms or other symptoms concerning for indolent malignancy.13

Diagnosis & Clinical Course

Plain films of our patient’s sacroiliac joints and lumbar spine were unremarkable. Hepatitis, tuberculosis, Lyme disease and parvovirus tests were negative. His uric acid level was within normal limits at 3.4 mg/dL (reference range: 4–8 mg/dL).

Based on his symptoms and the presence of RF, the leading diagnosis was palindromic rheumatism. The patient was scheduled for a follow-up visit in two weeks to discuss his diagnosis and start treatment.

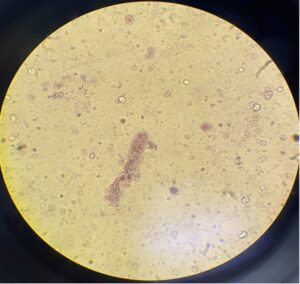

FIGURE 2. Microscopic examination of the patient’s urine sample shows one red blood cell cast. (Click to enlarge.)

Repeat laboratory tests prior to initiation of methotrexate revealed acute elevation of creatinine at 3.4 mg/dL, compared with his previous baseline of 1.19 mg/dL. A urinalysis showed +3 hemoglobin and +3 protein. Urine sedimentation showed many red blood cell casts (see Figure 2).

He was admitted for evaluation of acute kidney failure. Laboratory tests during admission revealed the presence of C-ANCA and proteinase-3 antigen >8 (normal range < 1) and negative cryoglobulin and anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibodies.

Chest radiography was unrevealing, without hilar adenopathy. Computed tomography (CT) showed small subpleural nodules in the right lower and left upper lobes. CT of his sinus without contrast showed a clear mastoid and minimal mucosal thickening of the maxillary sinuses without acute sinusitis.

His ophthalmologic exam was consistent with episcleritis and possible mild anterior scleritis.

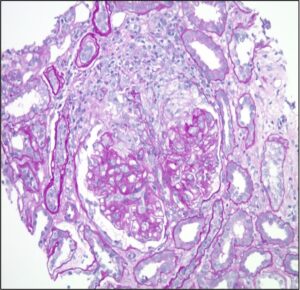

FIGURE 3. Kidney biopsy reveals pauci-immune necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis. (Click to enlarge.)

He underwent right-sided kidney biopsy, and the pathology was consistent with pauci-immune necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis with mild interstitial fibrosis (see Figure 3).

The patient was diagnosed with GPA and was administered pulse-dose methylprednisolone and four weekly infusions of rituximab in a dosage of 375 mg/m2 of body surface area.

Discussion

This case emphasizes the difficulties of early systemic vasculitides diagnosis and detection, which are always essential to avert serious morbidity and mortality.

AAV has a wide range of clinical manifestations, from single-organ limited to fulminant multi-system disease. Almost any organ can be affected, although the upper airways, lungs, kidneys, eyes and peripheral nerves are the most-often involved organs.

Clinical manifestations of AAV may develop over the course of weeks or months and may vary in frequency and order of presentation. The frequency of organ involvement at the onset of GPA includes upper respiratory tract (93%), lower respiratory tract (55%), musculoskeletal (54%), kidney (61%), ocular (40%), skin (23%) and nervous system (21%), and may reach up to 99%, 85%, 75%, 77%, 61%, 46% and 40%, respectively, during the disease course.1

Patients with AAV may exhibit organ-specific manifestations, in addition to non-specific constitutional symptoms, such fatigue, fever, weight loss, myalgias and polyarthritis, which could be mistaken for cancer, infections or other autoimmune diseases.1

Our patient presented with migratory polyarthritis, which is reported in approximately 25% of patients with AAV; however, it is not pathognomonic and is rarely the initial presenting symptom.2

As a result of the various presentations of AAV and a broad differential diagnosis due to its multi-systemic nature, a delay in diagnosis frequently occurs and may lead to significant morbidity and mortality.

In one large study among patients with various systemic vasculitides, the median time to diagnosis of vasculitis was seven months and approximately 73% of patients were initially misdiagnosed.14

Common disorders that share clinical symptoms with AAV include other forms of systemic vasculitides; autoimmune disorders, such as RA, SLE, sarcoidosis, and IgG-4 related disease; various malignancies, including, but not limited to, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and lymphomas; and infections, particularly infective endocarditis, mycobacterial or fungal disease.

Our patient was misdiagnosed with palindromic rheumatism and possible early RA, which shares clinical features with AAV, such as episcleritis/scleritis, lung nodules/cavitary lesions, interstitial lung disease and subcutaneous nodules, in addition to polyarthritis.

Leukocytosis and/or thrombocytosis on complete blood counts (CBCs) are not uncommon. The presence of anemia can be due to chronic inflammation, renal disease or acute blood loss due to alveolar hemorrhage. Nonetheless, all these studies are not characteristic of AAV and may be found in many other conditions. Further, the presence of RF and ANA occur in 40% and 50% respectively of patients with AAV and other connective tissue disorders, infections, and malignancies, which may create confusion during evaluation and establishing diagnosis.15-17

Similar to a false positive RF test, a positive ANCA test must be carefully interpreted because, aside from AAV, it can also be caused by drugs (e.g., hydralazine, propylthiouracil, cocaine), infective endocarditis, IBD, autoimmune hepatitis, SLE, Sjögren’s disease and RA.18

This case highlights the importance of adding AAV to potential causes of migratory polyarthritis and a false positive RF test because early recognition is vital. Screening for renal disease by obtaining a routine urinalysis is important in patients with AAV because early renal involvement is typically asymptomatic.

Adil Vural, MD, is a third-year internal medicine resident at Cleveland Clinic Fairview Hospital. He is going to start a rheumatology fellowship at Cleveland Clinic after his graduation.

Kinanah Yaseen, MD, is a staff rheumatologist at Cleveland Clinic. She completed her rheumatology fellowship, then a vasculitis fellowship at Cleveland Clinic.

References

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: An analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992 Mar 15;116(6):488–498.

- Kitching AR, Anders HJ, Basu N, et al. ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020 Aug 27;6(1):71.

- Ruddy S, Harris ED, Sledge CB, et al. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology (sixth ed.) Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2001.

- Koskinen E, Hannonen P, Sokka T. Palindromic rheumatism: Long-term outcomes of 60 patients diagnosed in 1967–1984. J Rheumatol. 2009 Sep;36:1873–1875.

- Katz SJ, Russell AS. Palindromic rheumatism: A pre-rheumatoid arthritis state? J Rheumatol. 2012 Oct;39:1912–1913.

- Moore TL. Parvovirus-associated arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000 Jul;12(4):289–294.

- Inman RD. Rheumatic manifestations of hepatitis B virus infection. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1982 May;11(4):406–420.

- Moro ML, Grilli E, Corvetta A, et al. Long-term chikungunya infection clinical manifestations after an outbreak in Italy: A prognostic cohort study. J Infect. 2012 Aug;65(2):165–172.

- Glaser C, Rieg S, Wiech T, et al. Whipple’s disease mimicking rheumatoid arthritis can cause misdiagnosis and treatment failure. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017 May 25;12(1):99.

- Zoma A. Musculoskeletal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2004;13:851–853.

- Visser H, Vos K, Zanelli E, et al. Sarcoid arthritis: Clinical characteristics, diagnostic aspects, and risk factors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002 Jun;61(6):499–504.

- Jamilloux Y, Kodjikian L, Broussolle C, et al. Sarcoidosis and uveitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014 Aug;13(8):840–849.

- Zupancic M, Annamalai A, Brenneman J, et al. Migratory polyarthritis as a paraneoplastic syndrome. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Dec;23(12):2136–2139.

- Sreih AG, Cronin K, Shaw DG, et al. Diagnostic delays in vasculitis and factors associated with time to diagnosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021 Apr 21;16(1):184.

- Moon JS, Lee DDH, Park YB, et al. Rheumatoid factor false positivity in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis not having medical conditions producing rheumatoid factor. Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Oct;37(10):2771–2779.

- Zhao X, Wen Q, Qiu Y, Huang F. Clinical and pathological characteristics of ANA/anti-dsDNA positive patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated vasculitis. Rheumatol Int. 2021 Feb;41(2):455–462.

- Ingegnoli F, Castelli R, Gualtierotti R. Rheumatoid factors: Clinical applications. Dis Markers. 2013;35:727–734.

- Hagen EC, Daha MR, Hermans JO, et al. Diagnostic value of standardized assays for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in idiopathic systemic vasculitis. Kidney Int. 1998 Mar;53(3):743–753.