The patient was admitted to the intermediate level of care but rapidly declined, requiring transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU). At that point, despite the initial negative test, the working diagnosis was of severe COVID-19 pneumonia due to the epidemiological considerations, his initial presentation with loss of taste and smell, and respiratory failure with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates.

In the ICU, he went on to develop severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and required intubation. Following intubation, he was noted to have a substantial quantity of bloody secretions in the endotracheal tube and underwent bronchoscopy, which showed significant blood in the airways. This blood did not clear with sequential lavage.

For his acute renal failure, continuous venovenous hemofiltration was started. Given the patient’s persistent bloody secretions, pulmonary-renal syndrome due to underlying vasculitis was suspected. He was started on plasmapheresis and pulse-dose glucocorticoids with 1 g methylprednisolone daily for five days.

He remained in the ICU for a total of 12 days. HIs ICU course was further complicated by worsening acute blood loss anemia and associated coagulopathy, requiring multiple transfusions with packed red blood cells, platelets, fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate. He had refractory hypoxemia, requiring high-fraction inspired oxygen (FiO2) up to 80–90%, as well as inhaled nitric oxide.

An evaluation for rheumatic disease was pursued (see Table 1). His serologies were positive for perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (P-ANCA) at a titer of 1:320 and anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO) antibodies at 41 units. His complement levels were low: C3 of 43 mg/dL and C4 of 13 mg/dL. Of note, cytoplasmic (C) ANCA, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-cardiolipin antibody, lupus anticoagulant, double-stranded DNA antibody and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody tests were negative. A second nasopharyngeal swab was performed on the second day of hospitalization, which again did not detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA.

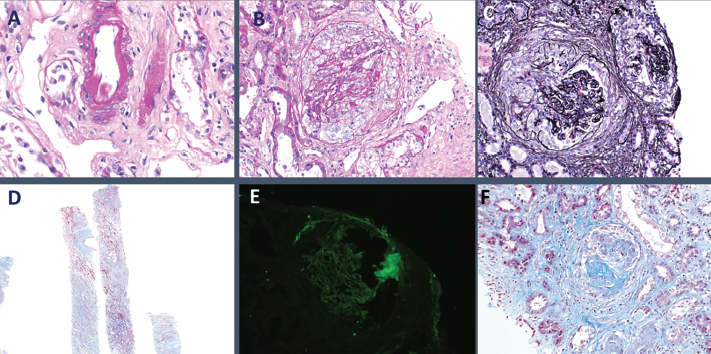

The patient received a total of seven daily sessions of plasmapheresis. Given worsening renal failure and ARDS, a renal biopsy was performed on hospital day 7, which revealed pauci-immune glomerulonephritis with crescent formation in 9 of 10 non-sclerotic glomeruli, consistent with microscopic polyangiitis with crescentic glomerulonephritis (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Histopathology from kidney biopsy. A) Arteriolar hyalinosis; B) Cellular crescents; C) Diffuse crescentic glomerulonephritis; D) Low-power objective; E) IgG negative; F) Segmental glomerulosclerosis.

After eight days of continuous venovenous hemofiltration, he transitioned to scheduled hemodialysis. He intermittently received broad-spectrum antibiotics for a total of five days due to concern for occult infection; however, all blood and respiratory cultures ultimately showed no growth.

In view of his lack of improvement clinically and no evidence of infections, on hospital day 11, he was started on 375 mg/m2 of intravenous rituximab weekly for total of four doses. Respiratory status improved remarkably with immunosuppression and plasmapheresis, and he was successfully extubated to high-flow nasal cannula the following day.

He transitioned to scheduled dialysis three times weekly, and he was ultimately discharged in good condition. He was discharged on 60 mg of prednisone daily, 1.5 g of atovaquone daily for Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis and scheduled for weekly rituximab infusions to complete a four-week induction.

Since discharge, he has continued with maintenance rituximab infusions and is currently taking 15 mg prednisone daily. He remains dialysis dependent and has transitioned to home peritoneal dialysis.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is thought to have begun in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and has developed into a pandemic of proportions not seen in modern history.1 In this setting of recurrent cases of similar clinical presentation of severe COVID-19, it is important to avoid cognitive errors that can lead to missing diagnoses with similar presentations. It is crucial to consider other causes for concurrent respiratory and renal failure.

An important cognitive error applicable to the current scenario is premature closure, which consists of believing enough information has been obtained to close the diagnosis without looking for further differential diagnoses.

A common bias that leads to premature closure is the anchoring bias, in which a diagnosis is not reconsidered despite new evidence that may undermine the initial assumption.4 An example of that applied to this case would be fixating on the fact that our patient presented during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic with respiratory symptoms, loss of taste and smell, and bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, without noting the severe renal failure with an active urinary sediment or the bloody secretions in the endotracheal tube after intubation. This is one of the most important lessons we learned from this case.

Treatment for the different types of ANCA-associated vasculitis is similar & depends on the presence of organ involvement & the level of disease activity.

The differential diagnosis for DAH is broad and includes many different pathophysiologic processes, including pulmonary capillaritis, bland hemorrhage and diffuse alveolar damage.3 The presence of DAH with glomerulonephritis, which is characteristic of pulmonary-renal, helps narrow the differential diagnosis.

Common etiologies of pulmonary-renal syndrome include microscopic polyangiitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), Goodpasture syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). This patient was diagnosed with MPA based on the clinical presentation of alveolar hemorrhage with renal failure and hematuria, positive P-ANCA and MPO, and kidney biopsy showing pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis without granulomas.5-7

MPA is an autoimmune medium- to small-vessel vasculitis grouped under ANCA-associated vasculitides (AAV). Common presentations include fever, fatigue, weight loss, arthralgias, cough, dyspnea, active urinary sediment with or without renal failure, purpura and neurologic dysfunction. Prodromal symptoms may last weeks to months without evidence of specific organ involvement.6,8,9

The diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and biopsy showing necrotizing vasculitis without immune deposits or granulomas.10,11 The presence of P-ANCA is suggestive of and helps differentiate MPA from GPA, which classically presents with C-ANCA and involves the nasopharynx.12 EGPA also presents with P-ANCA; however, it classically spares the kidneys and may involve the heart. Additionally, it is typically associated with peripheral blood eosinophilia. The presence of ANCAs against MPO is suggestive of MPA, and more specific than P-ANCA alone.9

In this case, the presence of a pulmonary-renal syndrome with active urinary sediment, elevated P-ANCA and anti-MPO antibodies led to a strong clinical suspicion for AAV, especially MPA, which prompted the kidney biopsy.

Table 1: Serology Results

| Rheumatology evaluation | Reference Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-nuclear Antibody | NEGATIVE | negative |

| Myeloperoxidase Antibody | 41 (H) | |

| Proteinase 3 Ab | 3 | |

| P-ANCA | 1:320 (A) | |

| C-ANCA | <1:20 | |

| Anti-cardiolipin IgA | <9.0 | |

| DNA(DS) Ab | NEGATIVE | negative |

| JO 1 Ab, IgG | 2 | |

| RHEUMATOID FACTOR | <20 | latest RR: <30 IU/mL |

| RNP ANTIBODY | 2 | |

| SSA Antibody | 2 | |

| SSB Antibody | 4 | |

| SM Ab, IgG | 4 | |

| SCL 70 Ab, IgG | 3 | |

| JO 1 Ab, IgG | 2 | |

| Kappa/Lambda FLC Ratio | 0.96 | |

| SCL 70 Ab, IgG | 3 | |

| SM Ab, IgG | 4 | |

| Cardiolipin Ab (IgG) | <9.0 | |

| Cardiolipin Ab (IgM) | 9.7 | |

| Cryoglobulin Screen | NEGATIVE | |

| Free Kappa Light chains | 12.08 (H) | |

| Free Lambda Light chains | 12.57 (H) | |

| ADAMTS 13 Activity | 27 (LL) | |

| ADAMTS 13 Inhibitor | <0.4 | |

| GLOMERULAR BASEMENT MEMBRANE | 2 |