Dermatomyositis (DM) is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy involving proximal muscle weakness and skin rash. An associated increased risk of malignancy is well established.1 The most frequent malignancies are related to the ovary, endometrium, lung, gastrointestinal tract, prostate, breast and lymphatics.2 On rare occasions, DM has been reported with certain types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, specifically cutaneous T cell lymphomas, such as mycosis fungoides, primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T cell lymphoma, NK/T cell lymphoma, angiotropic lymphoma and cutaneous γδ T cell lymphoma.3,4 The risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is increased within first year of a DM diagnosis; the risk of other cancers is increased for up to five years following diagnosis.2

Case Presentation

A 57-year-old white man presented with diffuse, ulcerated skin lesions. These lesions first developed two years before on his trunk, then spread to his extremities and oral mucosa. A previous muscle biopsy, performed due to weakness, showed evidence of DM, and a skin biopsy revealed interface dermatitis. Anti-PL-12, anti-signal recognition particle (SRP) and anti-Mi-2 antibodies were all present.

He had been noncompliant with prescribed disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and steroids.

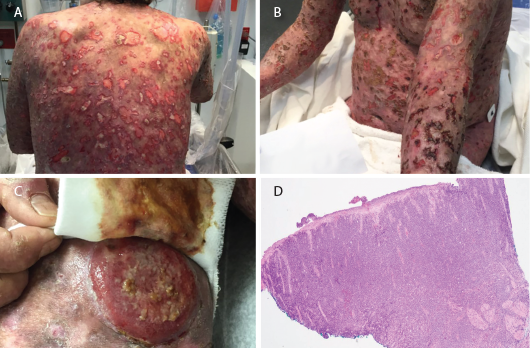

On exam, he had widespread, ulcerative skin lesions (see Figures 1A–B). His muscle strength was normal. Laboratory testing revealed normal creatinine kinase and aldolase levels. His white blood cell count was 12.3×103 cells/µL (reference range [RR]: 4.5–11×103 cells/µL), and his hemoglobin was 12 g/dL (RR: 12–16 g/dL). His erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 50 mm/hr (RR: 0–20 mm/hr), and his C-reactive protein was 108 mg/L (normal: <9 mg/L).

The patient was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, pulse steroids, hydroxychloroquine and mycophenolate. His skin lesions initially improved somewhat with treatment, only to worsen within three weeks. He was refractory to a second round of intravenous immunoglobulin. One month later, the patient developed multiple cutaneous tumors with a 12 lb. weight loss. A lesion biopsy confirmed mycosis fungoides (see Figures 1C–D). Despite radiation and chemotherapy, the patient died.

Figures 1 A–B: Numerous ulcerative lesions with sharply angulated edges are shown.

Figure 1C: A new tumorous lesion is shown on the patient’s leg.

Figure 1D: A biopsy of an ulcerated skin segment revealed an atypical mononuclear infiltrate.

Discussion

The association between malignancy and idiopathic inflammatory myopathy has long been reported. Overall, the malignancy risk in patients with myositis has been found to be 4.5-fold higher than in patients without idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. The relative risk of overall malignancy is 5.5 for DM and 1.62 for polymyositis. The relative risk was also significantly higher within the first year of diagnosis and higher in men.5

Proposed pathogenetic mechanisms of malignancy in autoimmune diseases include genetic predisposition, chronic immune stimulation and infections.6 Malignancy could also result from cross-reaction between muscle and tumor antigens, a paraneoplastic process or immunosuppressive treatments.7 DM often improves with treatment of malignancy, suggesting a parallel course.2

An analysis of the frequency and risk of specific cancers in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy found that of 618 DM patients, only three of 115 malignancies were non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Although the number of cases was low, the standardized incidence ratios were high. Ovarian and lung cancer had the highest standardized incidence ratios when compared with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.2

Skin is the second most frequently involved extranodal site for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, after the gastrointestinal tract. Most primary cutaneous non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are T cell derived, but nodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is B cell derived. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome are the two most common of 12 subtypes of cutaneous T cell lymphomas.8

In our literature review of DM, we found only six cases of cutaneous T cell lymphoma, with only one patient having mycosis fungoides. Despite its rarity, cutaneous T cell lymphoma should be considered in DM patients presenting with such skin findings as atypical plaques, nodules, ulcerations and tumor formation.3 Some of these findings were noted in our patient (see Figures 1A–D).

Because cutaneous T cell lymphoma lesions mimic those of other diseases and can be mistaken for atypical DM rash, diagnosis can be delayed. Sequential biopsies may be necessary to clinch the diagnosis and initiate proper treatment, as required in our patient (see Table 1).

Table 1: Description of Sequential Skin Biopsies

| Biopsy #1 | Interface dermatitis |

|---|---|

| Biopsy #2 | Dermal small vessel thrombotic vasculitis and coagulopathy with epidermal necrosis and fibrinopurulent inflammation (see Figures 1A–B) |

| Biopsy #3 | Lichenoid atypical large T cell lymphocytic infiltrate. Lymphocytes in the papillary dermis had cytologic atypia and strong positivity for CD3 and CD7. CD20 and CD30 were negative. |

| Biopsy #4 | Abnormal mononuclear infiltrate consistent with ulcerated T cell lymphoma/leukemia. Final diagnosis: Tumor stage mycosis fungoides, CD30 negative, large cell transformation. (see Figures 1C and 1D) |

Prognosis of mycosis fungoides depends on the extent of the involvement. Patients with limited skin involvement have a better prognosis; patients with diffuse skin involvement, tumor development or extracutaneous involvement have poor prognosis with increased mortality.9

Treatment options for mycosis fungoides in the advanced stage include chemotherapy, photodynamic therapy, radiation and bone marrow transplant.10

Despite its rarity, cutaneous T cell lymphoma should be considered in DM patients presenting with such skin findings as atypical plaques, nodules, ulcerations & tumor formation.

Screening guidelines for DM patients are needed for practicing rheumatologists. In a cohort of DM patients, it was found that age-appropriate cancer screening is not aggressive enough. In addition to your usual malignancy screening, computerized tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis also aid in a malignancy diagnosis.7 Features that should prompt investigation for malignancy include refractoriness to treatment, older age, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, severe muscle disease, low C4, cytopenias and hyperimmunoglobulinemia.3

Certain myositis-specific antibodies, such as anti-nuclear matrix protein-2 (anti-NXP-2) antibody and anti-transcriptional intermediary factor 1 γ (anti-TIF1γ) antibody, are associated with malignancy, but anti-Mi-2 antibodies are not. In a large cohort of malignancy-associated DM, 83% of patients were found with either anti-TIF1γ or anti-NXP-2 antibodies. Patients with either antibody had an increased risk of developing malignancy, with an odds ratio of 3.8.11 Anti-Mi-2 antibodies are associated with classic cutaneous DM, lower interstitial lung disease risk, milder muscle disease and good treatment response. Anti-NXP-2 antibodies are associated with juvenile DM, calcinosis and severe disease. Anti-TIF1γ antibodies are associated with early diagnosis of malignancy, severe cutaneous disease and ulcerations.12

Our case highlights the importance of heightened surveillance in DM patients despite the type of biomarkers present.12

Barrett Ford, MD, is a fellow in the Section of Rheumatology at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans.

Barrett Ford, MD, is a fellow in the Section of Rheumatology at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans.

Chandana Shilpa Kollipara Ravipati, DO, is an assistant professor of clinical medicine in the Section of Rheumatology at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center.

Chandana Shilpa Kollipara Ravipati, DO, is an assistant professor of clinical medicine in the Section of Rheumatology at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center.

Nirupa Patel, MD, is an associate professor of clinical medicine in the Section of Rheumatology at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center.

Nirupa Patel, MD, is an associate professor of clinical medicine in the Section of Rheumatology at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center.

References

- Bhatty O, Sen R, Nahas J. Cancer-associated myositis: A case report & review of the literature. Rheumatologist. 2019;59.1–7.

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: A population-based study. Lancet. 2001 Jan 13;357(9250):96–100.

- Yi L, Qun S, Wenjie Z, et al. The presenting manifestations of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma and T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous Y8 T-cell lymphoma may mimic those of rheumatic diseases: A report of 11 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2013 Aug;32(8):1169–1175.

- Connor B. Mycosis fungoides with dermatomyositis. Proc R Soc Med. 1972 Mar;65(3):251–252.

- Yang Z, Lin F, Qin B, et al. Polymyositis/dermatomyositis and malignancy risk: A metaanalysis study. J Rheumatol. 2015 Feb;42(2):282–291.

- Kojima M, Nakamura S, Futamura N, et al. Malignant lymphoma in patients with rheumatic diseases other than Sjögren’s syndrome: A clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of the Japanese literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1997 Apr;27(2):84–90.

- Leatham H, Schadt C, Chisolm S, et al. Evidence supports blind screening for internal malignancy in dermatomyositis: Data from 2 large US dermatology cohorts. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Jan;97(2):e9639.

- Fujii K. New Therapies and Immunological Findings in Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2018 Jun 4;8:198.

- Kim YH, Chow S, Varghese A, et al. Clinical characteristics and long-term outcome of patients with generalized patch and/or plaque (T2) mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol. 1999 Jan;135(1):26–32.

- PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Mycosis Fungoides (Including Sézary Syndrome) Treatment—Health Professional Version. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated 2019 Sep 20.

- Fiorentino DF, Chung LS, Christopher-Stine L, et al. Most patients with cancer-associated dermatomyositis have antibodies to nuclear matrix protein NXP-2 or transcription intermediary factor 1Y. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Nov;65(11):2954–2962.

- Gunawardena H, Betteridge ZE, McHugh NJ. Myositis-specific autoantibodies: Their clinical and pathogenic significance in disease expression. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009 Jun;48(6):607–612.