Etiopathogenesis: Obliterative bronchiolitis in RA was initially believed to be a complication of penicillamine and gold; however, arguing against this hypothesis is the fact that OB-RA still occurs in the present time, when penicillamine and gold are no longer used. Moreover, because most of the patients in the two largest case series were non-smokers, it is unlikely that OB-RA is a manifestation of typical COPD.6,7

It is now believed that OB reflects an autoimmune manifestation of RA, although evidence to support this hypothesis is sparse.4 Based on the study by Sweatman et al., the expression of human leukocyte (HLA) antigens B40 and DR1 is increased in OB-RA, but not in the non-RA OB population, suggesting a genetic predisposition for OB-RA.8 Induction of autoimmune response to airway proteins, such as collagen V and K-α 1 tubulin, has been recognized as important in the pathogenesis of OB in lung transplant patients.9,10 Whether similar autoantibodies play a role in the development of OB in non-transplant patients is unknown.

Clinical Presentation: Obliterative bronchiolitis in RA is noted to have a female preponderance, with the mean age at diagnosis in the sixth or seventh decade of life, possibly reflecting the higher prevalence of RA in this age group.

The most common presenting symptoms are chronic dyspnea, bronchorrhea and cough.6,7 The reported interval between the diagnosis of RA and the onset of OB is 10–15 years.6,7 It is unclear whether this delay in diagnosis is attributable to the insidious nature of the disease or a lack of clinical recognition. Additionally, some patients with OB-RA present initially with only respiratory symptoms; the characteristic musculoskeletal findings occur later.

Diagnostic Evaluation: Lack of knowledge about OB-RA or well-accepted diagnostic criteria make correct diagnosis challenging. In 2018, Lin et al. proposed diagnostic criteria for OB derived from lung transplant patients, defining OB as the presence of active respiratory symptoms, including dyspnea or cough, in the presence of histological features consistent with OB or pulmonary function testing and/or imaging evidence of obstruction in the absence of an alternative diagnosis (see Table 2, right).6,11

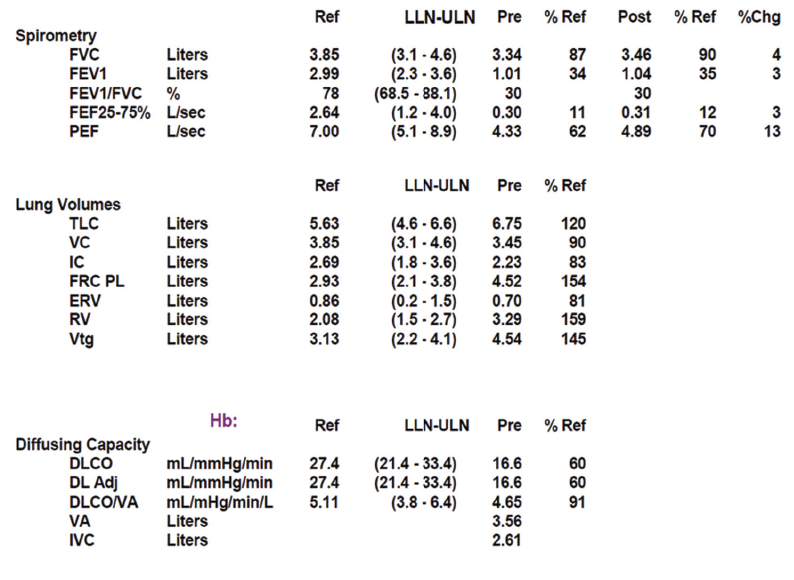

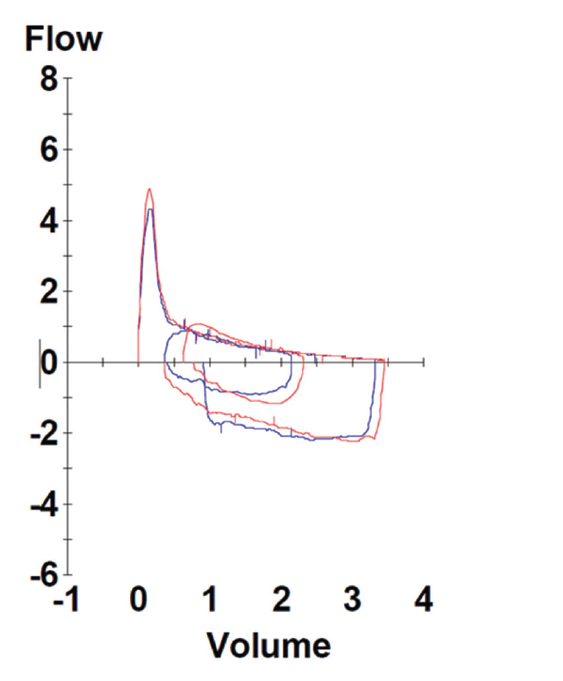

Spirometry in OB-RA reveals an obstructive impairment with poor response to bronchodilators. In particular, measures of small-airway function, such as forced-expiratory flow (FEF) 25–75, are markedly reduced. In addition, lung volume analysis typically shows air trapping evidenced by increased residual volume but a fairly preserved diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide compared with emphysema patients with a similar impairment.