During evaluation by his primary care doctor, his lab work demonstrated an elevated creatinine kinase, concerning for ongoing muscle damage, but the etiology of his symptoms was not identified.

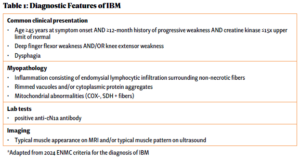

Over the next five years, he saw numerous specialists and underwent countless tests while his physical condition deteriorated. He underwent a muscle biopsy that was interpreted as polymyositis and was started on high-dose glucocorticoids for treatment. This failed to make an impact on his muscle strength. He was told not to exercise under the premise of causing further muscle damage, which likely exacerbated his weakness. Due to his progressive symptoms, he presented to the Johns Hopkins Myositis Center for a second opinion and was ultimately diagnosed with IBM based on his clinical history, muscle biopsy and physical exam (see Table 1 and Figures A, B & C).

By the time he was diagnosed, Mr. F had already experienced significant debility due to his disease and complications of futile high-dose glucocorticoid therapy, including weight gain, diabetes and gastrointestinal perforation.

During the years after his diagnosis, he was hospitalized four times, predominantly for episodes of aspiration pneumonia due to his progressive dysphagia. Because of his myopathy, he left each hospitalization increasingly debilitated. After one hospitalization, he returned home in a wheelchair, representing a loss of function that was never regained.

As his disease progressed, he faced significant psychosocial stressors and his quality of life suffered. A passionate social worker, he was forced to stop working due to the lack of accessible transportation options. With his progressive finger flexor weakness, he lost his ability to play the piano, one of his favorite activities. He began to suffer from depression and anxiety, exacerbated by his declining functional status. He became socially isolated due to shame surrounding his illness and soon became hesitant to even leave his house.

Throughout Mr. F’s illness, his wife was his primary and only care partner. She took ownership of managing his increasing needs. Without any professional guidance or social work support, she learned the complex process of insurance coverage for his different modalities of care. She obtained a fitted wheelchair, a Hoyer lift and a mobility van, and outfitted their apartment to make it accessible.

The day-to-day caregiving became overwhelming for her, both physically and emotionally. She bathed him, helped him with voiding and lifted his 200 lb. body in and out of his wheelchair. She sacrificed her own self-care to care for her husband; when she was forced to take respite for her own medical procedures, she experienced overwhelming feelings of guilt and failure. She no longer knew who she was beyond being a care partner for her husband.