“Our patients’ goals for their care aren’t always the same as ours. We’re typically focused on disease control, and they’re often focused on quality of life. Having ongoing discussions about care goals is the only way to know when it’s time to switch gears. Would you know when to refer your patients to palliative care? For an example of what can happen when that aspect of care gets overlooked, read our article, ‘Palliative Care for IBM,’ in the September issue of

The Rheumatologist ,” says Physician Editor Bharat Kumar, MD, MME, FACP, FAAAAI, RhMSUS.

Inclusion body myositis (IBM) is a slowly progressing muscle disease of unknown cause that currently has no effective treatment. IBM is the most common inflammatory myopathy in older individuals, with a rising prevalence of 18.2 per 100,000 in adults older than 50.1,2 The disease characteristically affects the quadriceps and finger flexors, and in later stages it can affect diffuse muscle groups, leading to significant physical disability. Dysphagia is a prominent symptom, often resulting from esophageal strictures and muscle weakness, and can lead to recurrent aspirations and malnutrition. The disease progresses slowly, often resulting in a delay in diagnosis, with some studies suggesting a gap of 4–5.6 years between symptom onset and diagnosis.3,4 Consequently, individuals often face significant loss in functional status, psychological distress and may have been exposed to unnecessary or inappropriate interventions by the time they are diagnosed.

Individuals with IBM face significant morbidity, in addition to having complex psychosocial, spiritual and interpersonal needs that would benefit from more robust and comprehensive supportive care. Palliative care focuses on quality of life by addressing physical symptoms, emotional and psychological distress, spiritual/existential distress and financial stressors that accompany serious life-limiting illnesses.5 It incorporates the patient’s values and goals in a multidisciplinary approach that allows for holistic, patient-centered care.

Palliative care can be provided by IBM clinical teams when they offer recommendations for disease-directed treatments, therapy and discussions about goals of care (referred to as primary palliative care) or directed by palliative care specialists in more complex cases. Despite the debilitating and incurable nature of the disease, palliative care has not been typically incorporated in the management of patients with IBM, and gaps in care exist.

The following case illustrates the need and opportunities for incorporating palliative care practices into care for people with IBM.

Case Report

Described as the “life of the party,” Mr. F was a professional pianist, an excellent chef and a compassionate social worker. In his mid-40s, he was experiencing minimal chronic health issues until he gradually began to have difficulty lifting his feet to climb stairs. Over a matter of months, his weakness progressed, and he developed significant fatigue and dysphagia.

During evaluation by his primary care doctor, his lab work demonstrated an elevated creatinine kinase, concerning for ongoing muscle damage, but the etiology of his symptoms was not identified.

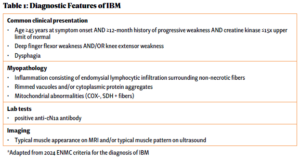

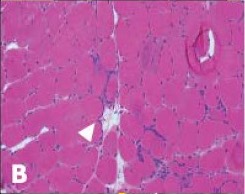

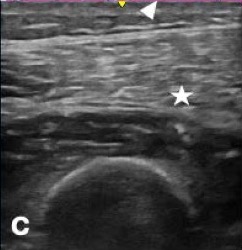

Over the next five years, he saw numerous specialists and underwent countless tests while his physical condition deteriorated. He underwent a muscle biopsy that was interpreted as polymyositis and was started on high-dose glucocorticoids for treatment. This failed to make an impact on his muscle strength. He was told not to exercise under the premise of causing further muscle damage, which likely exacerbated his weakness. Due to his progressive symptoms, he presented to the Johns Hopkins Myositis Center for a second opinion and was ultimately diagnosed with IBM based on his clinical history, muscle biopsy and physical exam (see Table 1 and Figures A, B & C).

By the time he was diagnosed, Mr. F had already experienced significant debility due to his disease and complications of futile high-dose glucocorticoid therapy, including weight gain, diabetes and gastrointestinal perforation.

During the years after his diagnosis, he was hospitalized four times, predominantly for episodes of aspiration pneumonia due to his progressive dysphagia. Because of his myopathy, he left each hospitalization increasingly debilitated. After one hospitalization, he returned home in a wheelchair, representing a loss of function that was never regained.

As his disease progressed, he faced significant psychosocial stressors and his quality of life suffered. A passionate social worker, he was forced to stop working due to the lack of accessible transportation options. With his progressive finger flexor weakness, he lost his ability to play the piano, one of his favorite activities. He began to suffer from depression and anxiety, exacerbated by his declining functional status. He became socially isolated due to shame surrounding his illness and soon became hesitant to even leave his house.

Throughout Mr. F’s illness, his wife was his primary and only care partner. She took ownership of managing his increasing needs. Without any professional guidance or social work support, she learned the complex process of insurance coverage for his different modalities of care. She obtained a fitted wheelchair, a Hoyer lift and a mobility van, and outfitted their apartment to make it accessible.

The day-to-day caregiving became overwhelming for her, both physically and emotionally. She bathed him, helped him with voiding and lifted his 200 lb. body in and out of his wheelchair. She sacrificed her own self-care to care for her husband; when she was forced to take respite for her own medical procedures, she experienced overwhelming feelings of guilt and failure. She no longer knew who she was beyond being a care partner for her husband.

Lack of consistent longitudinal specialty care hindered patient-centered communication and care. As Mr. F’s physical decline made regular travel to our specialty center impractical, his only contact with the medical system occurred when he was hospitalized. The providers he encountered were unfamiliar with the management and progression of IBM, preventing informed communication about care and prognosis. Although he was frequently in contact with the medical system, he had no conversations with clinicians about his prognosis, advance care planning or the implications of his progressive disease.

During one hospitalization for aspiration pneumonia, he underwent swallow studies that demonstrated significant dysmotility and was told he was no longer allowed to eat or drink by mouth. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube was placed with minimal conversation or guidance. He was told that he essentially had no choice in the decision because if he continued to eat and drink by mouth, he would die. After diligently not eating by mouth for a year, he felt overwhelmed by the emotional ramifications and the impact on his quality of life. With the support of his wife, he chose to begin eating by mouth once again, recognizing the risk of developing aspiration pneumonias. While his wife was supportive, every time he was hospitalized for aspiration he was criticized by his healthcare team for his decision to attempt oral feeding.

Goals-of-care discussions took place only in the days before his death. During a hospitalization for respiratory failure, for which Mr. F was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), Mrs. F ultimately asked for palliative care to be involved. The ICU team agreed, but Mr. F’s primary care doctor felt this decision was akin to giving up. Eventually, Mr. F passed away in the ICU due to respiratory failure secondary to IBM.

The unpredictability of Mr. F’s illness, combined with the lack of medical guidance throughout the process, led to significant distress for Mr. and Mrs. F. “You know what I think the problem was?” Mrs. F says, “I don’t think I knew when it was the end of life. There was a constant [uncertainty]. … Is it going to be this year or month? There were so many times I thought he was going to pass but he didn’t.”

Reflecting back, Mrs. F thinks earlier goals-of-care conversations would have been helpful. And as Mr. F continued to decline, there was no central person to guide them through the process.

Discussion

IBM is a serious and devastating illness without any known, effective cure. Excellent person-centered care of patients with IBM and their care partners must include palliative care—identification and management of total suffering, which includes physical, psychosocial, spiritual/existential and financial distress. Increasing access to palliative care requires educating rheumatologists about how to incorporate palliative care modalities into their management framework and identifying when referral to specialty palliative care is appropriate (see Table 2).

Complex symptom management is part of holistic IBM care.

Like Mr. F, many individuals with IBM have limited contact with the healthcare system after diagnosis because of the perception that available medical care is futile given the incurable nature of the disease; however, addressing symptom burden may not only relieve suffering, but may also improve the patient’s ability to continue receiving IBM-directed therapies.

For example, regular evaluation for swallowing dysfunction can allow for earlier interventions with such procedures as esophageal dilations or speech therapy, and prompt early conversations regarding PEG placement.6,7 Management of dysphagia, such as dietary modification, oral care and education, can be beneficial in managing symptoms for individuals with IBM and progressive swallowing dysfunction.8

Diaphragm weakness and respiratory failure can also be seen. When Mr. F’s respiratory status was declining, a pulmonologist put him on a bi-level positive airway pressure machine (BiPAP) machine at night, as well as a cough assist machine, interventions his wife felt improved his quality of life and prolonged his life. Routine incorporation of physical therapy and occupational therapy is the mainstay of treatment to maintain strength and prevent muscle atrophy for individuals with IBM. Early referral and regular monitoring can allow adoption of adaptive strategies/assistive devices to maintain physical function and prevent falls secondary to IBM.6,9

Further, Mr. F struggled with untreated depression and anxiety surrounding his illness, which were left unmanaged throughout the course of his illness and negatively impacted his quality of life.

High-quality communication facilitates exploration of goals & complex decision making.

Poor communication and the lack of timely goals-of-care discussions exacerbated the turmoil and isolation that Mr. and Mrs. F experienced. Discussions surrounding PEG tube placement were limited and did not incorporate Mr. F’s preferences surrounding his care. Informed, shared decision making is necessary when considering this procedure because it has not been found to prevent aspiration.

When Mrs. F needed to make healthcare decisions, she struggled with the uncertainty surrounding her husband’s prognosis. Incorporation of goals-of-care discussions earlier in the course of his illness would have allowed them to have relevant discussions surrounding therapies and advance care planning.10 High-quality communication surrounding goals of care in the management of serious illness are associated with improved quality of life and quality of death, and lead to reduced healthcare interventions.11–13

Once Mr. F was unable to travel for specialty care, the communication divide worsened because he lacked a regular longitudinal provider who was well versed in his disease. Incorporating telemedicine into the care of IBM patients may allow consistent communication, even when patients can’t attend visits in person, and decrease the sense of medical isolation.14

Care-partner burnout is a significant unmet need.

Palliative care incorporates management of interpersonal issues, such as care-partner burnout; for Mrs. F, her care-partner burnout was unaddressed. Studies suggest that care partners of individuals with IBM, as well as other inflammatory myopathies, face significant burden.15 Like up to half of family care partners, Mrs. F began to experience significant depression and anxiety, which went unaddressed as her husband’s health issues took the spotlight.16–18

Physicians have the opportunity to support care partners and minimize some of the burden they experience throughout the journey of illness by providing excellent communication, facilitating advance care planning and decision making, facilitating home care/respite care and providing emotional support.16 Support groups may also be helpful for the patient and family.

Multidisciplinary care is essential in complex illness management.

The support of social workers is often needed to navigate the complexity of the healthcare system and obtain needed resources. Without these structural supports, individuals like Mr. F are often left to ascertain which tools and equipment are needed to manage their mobility deficits without professional guidance, leading to ineffective and expensive efforts while potentially worsening deficits.

Individuals affected by IBM also face significant economic burden, including costs related to specialized equipment, home modifications and paid professional help.19 Prompt referral to social work can ease the burden that individuals with IBM and their families face in caring for their disease. In fact, a recent randomized controlled trial found that a nursing and social work palliative care telehealth team improved quality of life for individuals with serious chronic illness.20

Learn from Other Specialties

Understanding when to refer patients to palliative care specialists can be beneficial, helping patients with IBM receive appropriate care. Prior studies have found specialty palliative care is underutilized for patients with IBM admitted to the hospital, resulting in a missed opportunity to provide multidisciplinary quality care.21

Certain illness characteristics and conditions have been identified as triggers to consult specialty palliative care for individuals with severe neurologic disease.22 In motor-neuron disease, difficulties with respiration or eating, a rapid decline in mobility, weight loss and psychosocial distress have been identified as possible triggers for palliative care referrals.23 Using similar triggers to automate palliative care referral for patients with IBM may facilitate access to services that patients may not encounter otherwise.

Given that aspiration and respiratory failure are common causes of morbidity in patients with IBM, recurrent aspirations could serve as a sign of disease progression. Similarly, a change in physical status, such as worsening weakness or new dependence on an assistive device, may be another trigger. This should signal a need for more focused interventions and consideration for referral to specialist palliative care.

Alternatively, as in a model utilized in our institution for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, palliative care evaluations can be incorporated from the initial contact at the specialty center to normalize conversations and identify needs at each stage of the disease.24

In a very real sense, one could consider all available treatments for patients with IBM as palliative in nature. Yet complex symptom management, discussions around complex decisions and advance care planning, and partner support remain areas of care that need further addressing.

In Sum

The future of clinical care and research in IBM should evaluate and expand on palliative skills for IBM healthcare providers and the integration of specialty palliative care for these vulnerable patients. Given their expertise in IBM, multi-system disease and focus on whole-person care, rheumatologists are uniquely suited to lead this effort. Further, implementation of palliative care modalities for this patient population can serve as a stepping stone to integrating these practices for other complex, incurable rheumatic diseases.

Kamini E. Kuchinad, MD, MPH, completed her rheumatology fellowship at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and will be an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases, Oregon Health & Science University, and the VA Portland Health Care System, Portland, Ore.

Kamini E. Kuchinad, MD, MPH, completed her rheumatology fellowship at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and will be an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases, Oregon Health & Science University, and the VA Portland Health Care System, Portland, Ore.

Ambereen Mehta, MD, MPH, is an associate professor of palliative care in the departments of medicine and neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and works in the palliative care program at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore.

Ambereen Mehta, MD, MPH, is an associate professor of palliative care in the departments of medicine and neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and works in the palliative care program at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore.

David Wu, MD, is the director of the palliative care program at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, and an associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

David Wu, MD, is the director of the palliative care program at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, and an associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

Jemima Albayda, MD, is an associate professor of medicine, director of the rheumatology fellowship program and director of the Musculoskeletal Ultrasound and Injection Clinic in the Division of Rheumatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. She is a faculty member of the Johns Hopkins Myositis Center.

Jemima Albayda, MD, is an associate professor of medicine, director of the rheumatology fellowship program and director of the Musculoskeletal Ultrasound and Injection Clinic in the Division of Rheumatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. She is a faculty member of the Johns Hopkins Myositis Center.

References

- Shelly S, Mielke MM, Mandrekar J, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of inclusion body myositis: A 40-year population-based study. Neurology. 2021 May 25;96(21):e2653–e2661.

- Benveniste O, Guiguet M, Freebody J, et al. Long-term observational study of sporadic inclusion body myositis. Brain. 2011 Nov;134(Pt 11):3176–3184.

- Cortese A, Machado P, Morrow J, et al. Longitudinal observational study of sporadic inclusion body myositis: Implications for clinical trials. Neuromuscul Disord. 2013 May;23(5):404–412.

- Dobloug GC, Antal EA, Sveberg L, et al. High prevalence of inclusion body myositis in Norway; a population-based clinical epidemiology study. Eur J Neurol. 2015 Apr;22(4):672–679, e41.

- Gradwohl R, Brant JM. Hospital-based palliative care: Quality metrics that matter. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2015 Nov–Dec;6(6):606–610.

- Naddaf E. Inclusion body myositis: Update on the diagnostic and therapeutic landscape. Front Neurol. 2022 Sep 27:13:1020113.

- Taira K, Yamamoto T, Mori-Yoshimura M, et al. Obstruction-related dysphagia in inclusion body myositis: Cricopharyngeal bar on videofluoroscopy indicates risk of aspiration. J Neurol Sci. 2020 Jun 15:413:116764.

- Warren A, Buss MK. Death by chocolate: The palliative management of dysphagia. J Palliative Med. 2022 Jun;25(6):1004–1008.

- Tani T, Imai S, Fushimi K. Increasing daily duration of rehabilitation for inpatients with sporadic inclusion body myositis may contribute to improvement in activities of daily living: A nationwide database cohort study. J Rehabil Med. 2023 Apr 19:55:jrm00386.

- Bernacki RE, Block SD, American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Dec;174(12):1994–2003.

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008 Oct 8; 300(14):1665–1673.

- Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, et al. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir. 2011 Aug;38(2):268–276.

- Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end of life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 9;169(5):480–488.

- Worster B, Swartz K. Telemedicine and palliative care: An increasing role in supportive oncology. Curr Oncol Rep. 2017 Jun;19(6):37.

- Lubinus M, Hu YP, Wilson L, et al. Pos0070-pare caregiver burden among idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) caregivers. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 May;82(1):246.

- Rabow MW, Hauser JM, Adams J. Supporting family caregivers at the end of life: They don’t know what they don’t know. JAMA. 2004 Jan 28;291(4):483–491.

- Cannuscio CC, Jones C, Kawachi I, et al. Reverberations of family illness: A longitudinal assessment of informal caregiving and mental health status in the nurses’ health study. Am J Public Health. 2002 Aug;92(8):1305–1311.

- de Wit J, Bakker LA, Groenestijn AC, et al. Caregiver burden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2018 Jan;32(1):231–245.

- Capkun G, Tian H, Zhao C, et al. Economic burden of sporadic inclusion body myositis patients in the United States (P1.135). Neurology. 2016 Apr;86(16).

- Bekelman DB, Feser W, Morgan B, et al. Nurse and social worker palliative telecare team and quality of life in patients with COPD, heart failure, or interstitial lung disease: The ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024 Jan;331(3):212–223.

- Kuchinad K, Nadeem M, Mehta AK, et al. Palliative care utilization for hospitalized patients with inclusion body myositis: A nationwide study. J Clin Rheumatol. 2023 Sep;29(6):e130–e133.

- Chang RS, Poon WS. “Triggers” for referral to neurology palliative care service. Ann Palliative Med. 2018 Jul;7(3):289–295.

- McConvey K, Kazazian K, Iansavichene AE, et al. Triggers for referral to specialized palliative care in advanced neurologic and neurosurgical conditions. Neurol Clin Pract. 2022 Jun;12(3):190–202.

- Phillips JN, Besbris J, Foster LA, et al. Models of outpatient neuropalliative care for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2020 Oct 27;95(17):782–788.