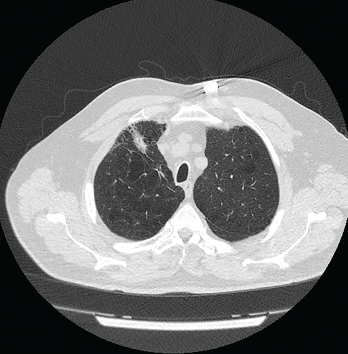

Figure 1: Computed Tomography VGstockstudio / shutterstock.com

Pulmonary nodules are common; most are benign, but the differential diagnosis is broad and includes life-threatening possibilities.1 Our patient is a former smoker who has a history of a complex autoimmune disease and multiple pulmonary nodules. This case was challenging, but clinical, radiographic and histologic clues helped lead to the correct diagnosis.

Case Presentation

The patient is a 74-year-old man with a past medical history remarkable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, emphysema, asbestos exposure and seropositive (rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibody) rheumatoid arthritis/scleroderma/systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) overlap syndrome. He has a 100 pack-year smoking history, although he quit smoking 22 years ago.

The patient was diagnosed with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis 15 years ago. His initial treatment was 15 mg of oral methotrexate weekly and 40 mg of subcutaneous adalimumab every 14 days. His methotrexate was tapered to 10 mg weekly, and the patient did well.

His disease course was complicated by the development of bulky rheumatoid nodules on the extensor surfaces of his elbows. After surgical removal of the nodules, he was taken off methotrexate and switched to 1 g of sulfasalazine twice daily to reduce the risk of rheumatoid nodulosis. Due to his moderately active disease, his therapy was changed from sulfasalazine to 20 mg of leflunomide daily.

The patient stopped taking adalimumab because he felt well.

The pulmonary nodules in rheumatoid pneumoconiosis develop cavitations or calcifications in 10% of cases.

Four years ago, the patient complained of Raynaud’s phenomenon. A physical examination revealed skin tightness from his fingertips to his proximal interphalangeal joints.

Serologic tests were positive for anti-nuclear antibody (ANA; 1:160, in a speckled pattern) and anti-centromere antibody (ACA; 2.8 AI; reference range [RR]: 0.0–0.9 AI). Tests for anti-SSA/Ro antibody, anti-SSB/La antibody, anti-nuclear ribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP) antibody, anti-Smith antibody and anti-topoisomerase I antibody were negative.

Two years ago, the patient had a flare of inflammatory arthritis, and treatment was started with 125 mg of subcutaneous abatacept weekly.

A few months later, the patient developed dyspnea due to serositis. He had no fever, cough, weight loss, night sweats or joint pain. A QuantiFERON gold test was negative for tuberculosis.

Results of pleural fluid studies included: albumin of 3.1 g/dL (RR: 3.5–5.0 g/dL), white blood cell count of 2535/µL (RR: 4,000–11,000/µL) with 44% neutrophils, glucose of 2 mg/dL (RR: 60–99 mg/dL) and a lactate dehydrogenase of 2,308 U/L (RR: 140–280 U/L).

Cultures for bacteria, fungi and acid-fast bacilli showed no growth. Cytology of the fluid revealed no malignant cells. The pleural fluid studies were consistent with an exudative, rheumatoid pleural effusion.

The patient experienced atypical chest pain. Evaluation for acute coronary syndrome was negative.

One month later, chest imaging showed a pericardial effusion and a repeat echocardiogram was consistent with tamponade. A pericardial window was performed to manage cardiac tamponade, and biopsy of the pericardium revealed fibrous tissue with congestion, chronic inflammation and granulation tissue.

Cultures of the pericardial fluid for bacteria, acid-fast bacilli and fungi were unrevealing. Anti-proteinase-3 (PR3) antibody was 4.3 U/mL (RR: 0–3.5 U/mL). The patient also had reduced C4 complement, 6.9 mg/dL (RR: 9–36 mg/dL), and IgM anti-cardiolipin antibody was mildly elevated at 39 U/mL (RR: 1–12 U/mL). The patient had no joint inflammation or renal disease at that time.

The patient had a history of urticaria after taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; therefore, he was treated with 10 mg of prednisone daily and 0.6 mg of colchicine twice daily. Sulfasalazine was discontinued because serositis was reported as a possible side effect of this drug in case reports, and 200 mg of hydroxychloroquine twice daily was initiated.

The following tests were performed: anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody <1 IU/mL (RR: 0–9 IU/mL), anti-RNP antibodies <0.2 AI (RR: 0.0–0.9 AI), anti-nuclear cytoplasmic antibodies <1:20 (RR: <1:20 titer), anti-myeloperoxidase antibody <9.0 U/mL (RR: 0.0–9.0 U/mL) and anti-proteinase-3 antibody <3.5 U/mL (RR: 0.0–3.5 U/mL).

Pulmonary function studies were consistent with moderate obstructive lung disease and moderate decrease in diffusion capacity. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax revealed severe emphysematous changes, a 1.8 cm x 1.6 cm pleural-based nodule in the anterior aspect of the right upper lobe and multiple sub-centimeter pulmonary nodules (see Figure 1).

Two percutaneous transthoracic biopsies of the largest left upper lobe and right upper lobe nodules showed patchy interstitial fibrosis and anthracotic pigmented macrophages. No malignancy or granuloma was identified on histology, and cultures for bacteria were negative.

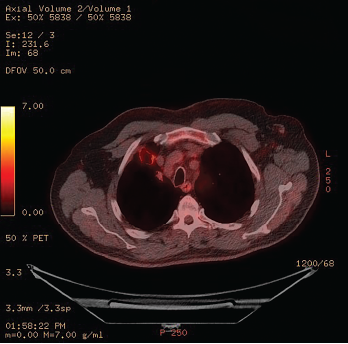

Figure 2: 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT Scintigraphy

A cavitary lesion with moderate uptake is seen in the right upper lobe.

The patient’s serositis improved and prednisone was tapered off. The patient improved clinically, but over six months his pulmonary imaging worsened. An 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) CT scintigraphy showed moderate uptake within a 2.8 cm x 2.1 cm nodular cavitary lesion in the anterior right upper lobe, which had enlarged since the previous PET scan (see Figure 2).

The possible causes of the cavitary lesion included malignancy, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis and rheumatoid nodule.

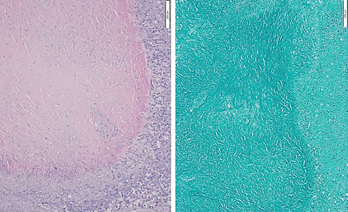

Ultimately, a wedge biopsy of the right upper lobe lesion was performed. A biopsy revealed a focal necrotizing granuloma. No malignant cells, fungi or acid-fast bacilli were identified (see Figure 3). The granulomata were well formed with well-margined central necrosis and palisading histiocytes. No features of necrotizing arteritis were seen. The carbon deposition surrounding the nodules was greater than expected with cigarette smoke exposure alone.

Considering the patient’s history of occupational dust exposure, this is consistent with Caplan syndrome or rheumatoid pneumoconiosis, which was the final diagnosis in this case.

Leflunomide is associated with pulmonary nodulosis in several case reports.2 So he was tapered off leflunomide and is doing well.

Discussion

We present the case of a former smoker with complex autoimmune disease and cavitary pulmonary nodules. Pulmonary nodules are focal opacities on imaging that measure up to 3 cm in diameter and are surrounded by lung parenchyma.1 The differential diagnosis for our patient’s pulmonary nodules included malignancy, medication effect, indolent infection and autoimmune disease. Diagnosis is based upon clinical features, laboratory results, radiographic features and histology.3

Figure 3: Hematoxylin & Eosin Stain, Low Power

A biopsy of the right upper lobe of the lung shows a well-margined granuloma with palisading histiocytes. Ziehl-Neelsen staining was negative for acid-fast bacilli.

Malignancy was of concern due to the patient’s age and history of smoking and asbestos exposure as a construction contractor. Characteristics of pulmonary nodules on imaging are helpful to assess the risk of malignancy. An upper lobe location increases risk of lung cancer; solid and irregular or spiculated lesions have the highest cancer risk.4 Chronic pulmonary cavities are cavitary lesions present for more than 12 weeks. These lesions are suggestive of chronic infection, autoimmune conditions or malignancy.

The size of pulmonary nodules is also important. For nodules less than 5 mm in diameter the risk of cancer is <0.5%.4 Larger nodules are subject to surveillance to detect growth. Faster growth predicts an increased likelihood of malignancy. Risk prediction models, such as the Brock model, are used to calculate risk of cancer.5 Our patient’s cancer probability calculated by the Brock University cancer prediction equation was 25.49%. PET-CT scanning is recommended for nodules with calculated risk of malignancy greater than 10%.

Although higher maximum standardized uptake value is suggestive of malignancy, tissue diagnosis remains the gold standard.6 Primary lung cancer is more likely with a solitary cavitary lesion in the lung.7,8 The most common type of cavitary primary lung cancer is squamous cell carcinoma.8 Wall thickness of more than 24 mm and consolidation around the lesion are also suggestive of malignancy. Lung metastases from the gastrointestinal tract, breast and sarcoma commonly cavitate.7 Clinically, the patient may present with cough and weight loss but acute symptoms like fever are uncommon.7 Histology is necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Our patient was immunosuppressed and at risk for opportunistic pulmonary infections. Infectious granulomas are the most common cause for benign nodules.9 Causes of infectious cavitary lung lesions are bacterial lung abscess, necrotizing pneumonias, septic emboli, acute fungal infection, and typical and atypical mycobacterium infection. Bacterial pathogens that may cause lung cavities include: microaerophilic streptococci, Streptococcus viridans, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Hemophilus infuenzae.7,8

In the case of necrotizing pneumonia, the patient will generally present with symptoms of infection that may progress to respiratory failure and septic shock. Lung abscesses present as a cavitary lesion with or without a fluid level. The cavitary wall is thick with peripheral contrast enhancement and a necrotic center. They are usually unilateral and mostly involve posterior segments of the upper lobes and superior segments of the lower lobes.7,8 Septic emboli cause multiple peripheral or subpleural nodules with evidence of various stages of cavities in up to 85% of patients.8 Blood tests show leukocytosis with a left shift and elevated procalcitonin level. In our case, the indolent clinical course made bacterial infection less likely.

Blood cultures, beta-D-glucan level and galactomannan level may be helpful to evaluate fungal lung infection. Possible fungal pathogens include Cryptococcus neoformans, Coccidioidomycosis, Aspergillus fumigatus and mucormycosis.8 Cavitary lung lesions are found mostly in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. There will be multiple pulmonary nodules with halo sign or ground glass opacities surrounding a solid central core.8

In patients with mycobacterial infection, we expect a positive interferon gamma release assay or tuberculin skin test. Mycobacteria can be detected in sputum microscopy or culture. Mycobacteria are acid fast. They do not decolorize with acidified alcohol after staining with carbol-fuchsin or auramine-rhodamine.8

Tuberculosis is caused by M. tuberculosis.10 The most common nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTB) are M. avium-intracelluare and M. kansaii.7 Patients who are immunosuppressed and have structural lung disease are at risk for infection by NTB.8 Sometimes these patients are asymptomatic. Symptomatic patients may present with low grade fever, chronic cough, weight loss, anorexia and hemoptysis.7,8 Our patient had no fever and repeated cultures and tests for infection were negative.

Pulmonary nodules may be caused by autoimmune disease. Pulmonary manifestations occur in 60–80% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.8 Rheumatoid nodules are unusual; they are found more commonly on lung biopsy than in radiographs.11 Risk factors for rheumatoid nodules include longstanding disease, presence of rheumatoid factor, cigarette smoking, subcutaneous nodules and long-term treatment with methotrexate.11,12 They are usually asymptomatic.

Patients with a pulmonary rheumatoid nodule may present with symptoms of infection, pleural effusion or bronchopulmonary fistula, if the nodules cavitate or rupture. Uncomplicated nodules have a variable course but sometimes improve with treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.12 Case reports have shown an association between rheumatoid nodules and bronchogenic carcinoma.11 Biopsy is needed to exclude infection or malignancy. The histopathology of a rheumatoid nodule shows a central zone of acellular fibrinoid necrosis surrounded by a zone of palisading epithelioid cells, which in turn are surrounded by a collar of lymphocytes.11

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation.8 It is a small vessel vasculitis that commonly involves the respiratory tract and kidneys.7 Upper and lower respiratory tract involvement is common. Patients may experience epistaxis, recurrent sinusitis, saddle nose deformity, cough, stridor, wheezing and hemoptysis. Without treatment, the disease can cause multi-organ damage.13 About 80–90% of GPA patients with active disease are positive for anti-PR3-ANCA.

Although our patient had a low titer anti-PR3 ANCA, false positives may occur in patients with other autoimmune diseases.14 In addition, silica and asbestos exposure were linked to ANCA-associated vasculitis in a case series.15 Lung nodules are the most common form of pulmonary involvement in GPA. They are usually multiple, bilateral and without zonal predilection.8 Histopathology is required to make the confirmatory diagnosis.

Three distinctive patterns of histopathology are seen in GPA: necrosis, granulomatous inflammation and vasculitis. The vasculitis in GPA is associated with fibrinoid necrosis of small to medium sized vessels. The granulomata produce large, irregular geographic areas of necrosis. Sometimes in acute inflammation only scattered multinucleated giant cells are found.16 The granulomata seen in our case were well formed with regular, well-marginated areas of necrosis. Our patient had had no other manifestations of systemic vasculitis.

Rheumatoid pneumoconiosis (RP) or Caplan syndrome was described in 1953. These patients with rheumatoid arthritis and dust exposure, especially silica, develop rapidly progressive peripheral pulmonary nodules.17 Although prevalence in the U.S. is only 0.89%, this was a concern for our patient, who worked as a construction contractor.17 The pulmonary nodules in RP develop cavitations or calcifications in 10% of cases. Histologically, RP nodules typically have a layer of black dust surrounding a central necrotic area.17 Overall, the prognosis for this condition is good.

In Sum

Our patient, with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis/scleroderma/SLE overlap syndrome and multiple cavitary pulmonary nodules, had a final diagnosis of rheumatoid pneumoconiosis. His clinical history of seropositivity for rheumatoid factor, occupational dust exposure and lack of respiratory and constitutional symptoms is consistent with the diagnosis.

Monsoon Rashid, DO, is a rheumatology fellow at State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn.

Monsoon Rashid, DO, is a rheumatology fellow at State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn.

Deana Lazaro, MD, is chief of rheumatology at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare Center, Brooklyn campus, and the program director for the SUNY Downstate Rheumatology fellowship program.

Deana Lazaro, MD, is chief of rheumatology at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare Center, Brooklyn campus, and the program director for the SUNY Downstate Rheumatology fellowship program.

References

- Au-Yong ITH, Hamilton W, Rawlinson J, Baldwin DR. Pulmonary nodules. BMJ. 2020 Oct 14;371:m3673.

- Balkarli A, Cobankara V. Pulmonary nodulosis associated with leflunomide therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: Report of four cases and review of the literature. J Clin Exp Invest. 2016 Mar;7(1):98–102.

- Gafoor K, Patel S, Girvin F, et al. Cavitary lung diseases: A clinical-radiologic algorithmic approach. Chest. 2018 Jun;153(6):1443–1465.

- Swensen SJ, Silverstein MD, Ilstrup DM, et al. The probability of malignancy in solitary pulmonary nodules. Application to small radiologically indeterminate nodules. Arch Intern Med. 1997 Apr 28;157(8):849–855.

- Tammemägi MC, Church TR, Hocking WG, et al. Evaluation of the lung cancer risks at which to screen ever- and never-smokers: Screening rules applied to the PLCO and NLST cohorts. PLoS Med. 2014 Dec 2;11(12):e1001764.

- Sim YT, Goh YG, Dempsey MF, et al. PET–CT evaluation of solitary pulmonary nodules: Correlation with maximum standardized uptake value and pathology. Lung. 2013 Dec;191(6):625–632.

- Parkar AP, Kandiah P. Differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesions. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2016 Nov 19;100(1):100.

- Campainha S, Gonçalves M, Tavares V, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis initially misdiagnosed as lung cancer. Rev Port Pneumol. Jan-Feb 2013;19(1):45–48.

- Higgins GA, Shields TW, Keehn RJ. The solitary pulmonary nodule. Ten-year follow-up of Veterans Administration-Armed Forces cooperative study. Arch Surg. 1975 May;110(5):570–575.

- Wickrematilake G. Complicated rheumatoid nodules in lung. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2020 Dec 2;2020:6627244.

- Sagdeo P, Gattimallanahali Y, Kakade G, Canchi B. Rheumatoid lung nodule. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Oct 29;2015:bcr2015213083.

- Shaw M, Collins BF, Ho LA, Raghu G. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated lung disease. Eur Respir Rev. 2015 Mar;24(135):1–16.

- Masuta P, Amzuta I. Solitary pulmonary nodule: A diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2019 Nov 21;2019:5242634.

- Merkel PA, Polisson RP, Chang Y, et al. Prevalence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in a large inception cohort of patients with connective tissue disease. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Jun 1;126(11):866–873.

- Rihova Z, Maixnerova D, Jancova E, et al. Silica and asbestos exposure in ANCA-associated vasculitis with pulmonary involvement. Ren Fail. 2005;27(5):605–608.

- Masiak A, Zdrojewski Z, Peksa R, et al. The usefulness of histopathological examinations of non-renal biopsies in the diagnosis of granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Reumatologia. 2017;55(5):230–236.

- Schreiber J, Koschel D, Kekow J, et al. Rheumatoid pneumoconiosis (Caplan’s syndrome). Eur J Intern Med. 2010 Jun;21(3):168–172.