Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is a systemic autoinflammatory disorder characterized by persistent fever at regular intervals, arthralgias or arthritis, rash, sore throat and neutrophilic leukocytosis.1,2 Significant elevation in ferritin levels is characteristic and tends to correlate with disease activity. Additional clinical features may include myalgias, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, serositis, myocarditis, abnormal liver function tests and development into potentially life-threatening macrophage activation syndrome (MAS).3

Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is a systemic autoinflammatory disorder characterized by persistent fever at regular intervals, arthralgias or arthritis, rash, sore throat and neutrophilic leukocytosis.1,2 Significant elevation in ferritin levels is characteristic and tends to correlate with disease activity. Additional clinical features may include myalgias, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, serositis, myocarditis, abnormal liver function tests and development into potentially life-threatening macrophage activation syndrome (MAS).3

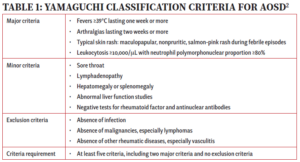

The diagnosis of AOSD poses challenges due to the nonspecific clinical features and the lack of specific diagnostic tests. Alternative diagnoses, including infections, drug reactions, malignancies and systemic rheumatic diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis, must be excluded. Various classification criteria have been suggested, and Yamaguchi criteria are commonly used to aid in classification (see Table 1).2,3

The typical AOSD rash is an evanescent, salmon-colored, maculopapular rash that often accompanies a fever and is seen in up to 80% of patients.3 However, an under-recognized, atypical rash that presents as persistent pruritic plaques or papules on extremities and torso, mimicking dermatomyositis, may also be found in a subset of patients with this disorder.4–10 This rash demonstrates distinctive features on histology, including parakeratosis, dyskeratosis and necrotic keratinocytes in the upper half of the epidermis and, if recognized, can facilitate an earlier diagnosis.4,6

Here, we report on a patient with AOSD and distinctive skin biopsy features consistent with the atypical (persistent) eruption of AOSD preceding a diagnosis of breast cancer.

FIGURES 1A, 1B & 1C (above): Persistent hyperpigmented plaques on the chest and neck, upper lateral arm and back. (Click to enlarge each.)

Case Presentation

A 28-year-old woman presented with a three-week history of migratory arthralgias and myalgias, daily fevers up to 103ºF (39ºC) and a diffuse pruritic rash on her arms, legs, chest and back. Prior to admission, she presented to an outside emergency department and an urgent care facility five times within one month with similar symptoms and was diagnosed with a viral syndrome.

Tests for respiratory viral infections, including influenza and COVID-19, were negative. She took non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with minimal relief of her arthralgias and myalgias. On admission, she was febrile to 38.5ºC, tachycardic to 112 beats per minute and hypertensive at 143/91 mmHg. Auscultation of the heart did not reveal any murmurs, gallops or rubs, and lung auscultation revealed vesicular breath sounds without rales, rhonchi or wheezes. Her skin exam revealed lichenified hyperpigmented plaques (see Figures 1 & 2) on her upper arms, back, around her neck and on her upper chest and legs, with excoriated areas concentrated on extensor surfaces, grossly normal nailfolds, normal muscle strength and diffuse joint tenderness without synovitis.

- A white blood cell count (WBC) of 26×109/L (reference range [RR]: 4.2–10.3×109/L), with 85% neutrophils;

- Hemoglobin (Hgb) at 7.8 g/dL (RR: 11.2–15.7 g/dL);

- Platelets at 361×109/L (RR: 160–383×109/L);

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 146/L (RR: 10–35/L);

- Alanine transaminase (ALT) of 151/L (RR: 10–35/L); and

- Albumin of 3.2 g/dL (RR: 3.5–5.2 g/dL).

Tests were normal for alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin. Other tests showed:

- An international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.7 (RR 0.9–1.1);

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) at 696 U/L (RR: 135–214 U/L);

- Haptoglobin at 410 mg/dL (RR: 16–200 mg/dL);

- Ferritin at 13,660 ng/mL (RR: 13–150 ng/mL), peaked at 21,000 ng/mL;

- C-reactive protein (CRP) at 23.7 mg/dL (RR: <0.5 mg/dL); and

- An erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of >130 mm/hr (RR: 0–20 mm/hr).

FIGURES 2A, 2B & 2C (above): Persistent hyperpigmented confluent plaques on the upper thigh, and more linear plaques on the inner thighs and lower leg. (Click to enlarge.)

She had elevated fibrinogen levels. Her creatinine kinase (CK), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), creatinine and electrolytes were normal. She also had an unrevealing urinalysis, except a protein count of 100 mg/dL, with a urine protein to creatinine ratio of 0.7.

An evaluation for infectious causes for her condition was negative for syphilis via rapid plasma reagin (RPR), HIV antigen/antibody and RNA, anti-hepatitis A antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen and core antibody IgM/IgG, and anti-hepatitis C antibody, mononucleosis, tuberculosis (T-spot), respiratory viruses, COVID-19, parvovirus B-19, chlamydia and gonorrhea.

One of two initial blood cultures grew Streptococcus mitis/oralis, which was thought to be contaminant. Two repeat blood cultures were negative.

The rheumatology evaluation revealed anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) titers below 1:80. Levels of anti-Jo-1, anti-ribonucleoprotein antibody (RNP), anti-Scl-70 antibody, anti-Smith antibody, anti-SSA antibody (Ro), anti-SSB antibody (La), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (CCP) were within normal limits. Her rheumatoid factor (RF) was 21 IU/mL (RR: 0–14 IU/mL), and she had an elevated C3 level, with a normal C4.

Imaging studies, including chest and knee X-rays and liver ultrasound, were unrevealing, as was echocardiography, without valvular vegetations.

The patient was initially treated empirically with vancomycin and cefepime for possible bacterial infection, which were discontinued after two days following the negative blood cultures.

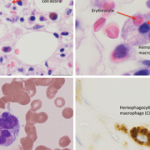

Skin biopsy pathology reported acanthosis, hyperkeratosis and dyskeratosis in the upper epidermis, consistent with the atypical (persistent) eruption of AOSD.

She was diagnosed with AOSD based on clinical features of daily fevers for more than a week, arthralgias for more than two weeks, leukocytosis (>10,000 with predominant polymorphonuclear leukocytes), elevated liver function tests (LFTs) and inflammatory markers with very high ferritin, a negative infectious evaluation, no evidence of malignancy and positive skin biopsy. She was classified as having AOSD based on the Yamaguchi criteria (see Table 1).

She was started on 100 mg of anakinra daily, experiencing complete resolution of her clinical symptoms and rapid improvement of her laboratory abnormalities, with down-trending ferritin and normalized WBC in a week.

She was discharged on 40 mg of prednisone daily with a taper due to denial of insurance coverage for anakinra, and her symptoms reappeared during the prednisone taper. Ultimately, anakinra was approved by her insurance company. Due to injection-site reactions, she was switched to monthly infusions of 8 mg/kg of tocilizumab.

At one year follow-up, the patient remained in clinical remission, with improved residual hyperpigmentation. Twenty months after the diagnosis of AOSD, she was diagnosed with ductal carcinoma of the breast.

Discussion

The most common rash associated with AOSD is a salmon-colored, non-pruritic, evanescent, maculopapular rash involving the extremities and trunk, usually accompanying the fever and disappearing when the fever subsides. The histopathology of the evanescent rash is nonspecific and may be more useful for excluding alternative diagnoses, such as drug reactions.

Complicating matters is that the skin rash of AOSD may also present as persistent, pruritic, hyperpigmented papules, plaques or linear pigmentation. These lesions are commonly found on the trunk and extensor surface of the extremities, and often resemble lesions associated with dermatomyositis.4–10 The histopathology reveals distinctive features, including dyskeratosis, necrotic keratinocytes, parakeratosis primarily observed in the superficial layers of the epidermis, without concurrent basilar dyskeratosis, and a sparse, superficial dermal infiltrate, often containing neutrophils or less frequently lymphocytes, without vasculitis.4,6,10 This rash may be associated with more severe disease and a worse prognosis, consistent with our case; our patient had an incomplete response to high-dose prednisone but responded well to interleukin (IL) 1 and IL-6 blockade.10,11

A further diagnostic challenge associated with AOSD is that malignancies can present with symptoms that resemble AOSD, and also that AOSD may rarely be a paraneoplastic phenomenon that precedes the diagnosis of malignancy.12 In a systematic literature review conducted by Hofheinz et al., 36 cases of AOSD associated with malignancy were reported, with half of them diagnosed with solid tumors and the other half with hematologic malignancies.13 The median time from AOSD diagnosis to the malignancy diagnosis was nine months. Among cases with solid tumors, the most frequent types were ductal breast cancer (n=4) and non-small cell lung cancer (n=3). Sixty-seven percent of the patients with solid cancer had metastatic involvement at the time of diagnosis. It is unclear in this case how the AOSD was related to the subsequent diagnosis of ductal carcinoma.

These reports and our reported case suggest that a heightened clinical index of suspicion for malignancy is warranted in patients presenting with signs and symptoms resembling AOSD. Several red flags have been reported to be associated with malignancy in AOSD, including older age, atypical rash, extremely high levels of LDH, atypical cells in the differential blood count and high levels of the soluble IL-2 receptor.13 It is unclear whether the atypical rash noted in this case report may provide diagnostic clues about the presence of an occult malignancy. Regardless, in such cases, some suggest positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET-CT) to evaluate for the presence of solid tumors.13

Kubra Bugdayli, MD, is a board-certified rheumatologist practicing at United Hospital Center, Bridgeport, W.Va. She completed her rheumatology fellowship at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

Dr. Eldaboush

Ahmed Eldaboush, MD, is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia. He obtained his medical degree from Al-Azhar University, Cairo.

Dr. Aggarwal

Sanjana Aggarwal, MBBS, is a medical graduate of Hamdard Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Delhi, India. She is currently working in a secondary level government hospital in Delhi as a junior resident in the Department of Medicine.

Dr. Bermas

Bonnie L. Bermas, MD, is the Dr. Morris Ziff Distinguished Professor in Rheumatology and clinical director of the Rheumatic Diseases Division at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

References

- Feist E, Mitrovic S, Fautrel B. Mechanisms, biomarkers and targets for adult-onset Still’s disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018 Oct;14(10):603–618.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s disease. J Rheumatol. 1992 Mar;19(3):424–430.

- Gerfaud-Valentin M, Jamilloux Y, Iwaz J, Sève P. Adult-onset Still’s disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014 Jul;13(7):708–722.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: A characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010 Sep;37(9):932–937.

- Lee JY, Hsu CK, Liu MF, Chao SC. Evanescent and persistent pruritic eruptions of adult-onset still disease: A clinical and pathologic study of 36 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Dec;42(3):317–326.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Jun;52(6):1003–1008.

- Lübbe J, Hofer M, Chavaz P, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease with persistent plaques. Br J Dermatol. 1999 Oct;141(4):710–713.

- Ohashi M, Moriya C, Kanoh H, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease with dermatomyositis-like eruption. J Dermatol. 2012 Nov;39(11):958–960.

- Fernández Camporro Á, Rodriguez Diaz E, Beteta Gorriti V, et al. Still disease with persistent atypical dermatomyositis-like skin eruption: Two cases associated with macrophage activation syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022 Nov;47(11):1991–1994.

- Narváez Garcia FJ, Pascual M, López de Recalde M, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease with atypical cutaneous manifestations. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Mar;96(11):e6318.

- Nagai Y, Hasegawa M, Okada E, et al. Clinical follow-up study of adult-onset Still’s disease. J Dermatol. 2012 Nov;39(11):898–901.

- Korekawa A, Nakajima K, Nakano H, Sawamura D. Paraneoplastic syndrome associated with chronic myelogenous leukemia mimicking adult-onset Still’s disease. J Dermatol. 2020 Feb;47(2):e67–e69.

- Hofheinz K, Schett G, Manger B. Adult onset Still’s disease associated with malignancy–cause or coincidence? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016 Apr;45(5):621–626.