Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI) is a rare gastrointestinal pathological process defined by the presence of gas within the layers of the intestinal wall, commonly within the mucosa and submucosa of the small and large intestines.2,3 PCI has been described in the literature in association with various connective tissue diseases, including scleroderma, mixed connective tissue disease, Sjögren’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus.1,3 Here, we present a case of PCI in a patient with limited systemic sclerosis.

Clinical Presentation

A 69-year-old woman presented to the rheumatology clinic to establish care. She was diagnosed with limited systemic sclerosis in 2007 by a dermatologist based on sclerodactyly, Raynaud’s phenomenon and telangiectasias. She had never seen a rheumatologist before, nor had she required treatment with any disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD).

She reported a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and was followed by a gastroenterologist. She denied dysphagia, abdominal pain and distension. She denied any cardiopulmonary symptoms and had no known history of interstitial lung disease or pulmonary hypertension.

Her medical history also included chronic musculoskeletal pain, for which she was treated chronically with ibuprofen and hydrocodone/acetaminophen. She had undergone a partial colectomy in 2011 and was unable to provide any specific reason or diagnosis for this procedure.

Physical examination revealed bilateral sclerodactyly distal to the proximal interphalangeal joints. Multiple telangiectasias were noted on the tongue and the dorsal and ventral aspects of both hands. The cardiac exam did not reveal a murmur. Pulmonary auscultation was notable for crackles at the base of the left lung. Diffuse soft tissue and joint tenderness were noted, without evidence of inflammatory arthritis.

Laboratory testing performed before her appointment revealed an anti-nuclear antibody titer of >1:1280 [reference range: negative] with a centromere pattern.

The patient’s abnormal lung exam was evaluated with a two-view chest X-ray. This incidentally revealed pneumoperitoneum (see Figure 1).1

Due to geographic and transportation constraints, the patient was unable to return to the clinic for a repeat evaluation; therefore, she was contacted by telephone. She reported having mild abdominal discomfort and bloating, the nature and duration of which she was not able to clearly describe. She denied any sudden severe abdominal pain, trauma, fever or recent abdominal surgery or procedures. Prompt evaluation at the nearest emergency department was recommended.

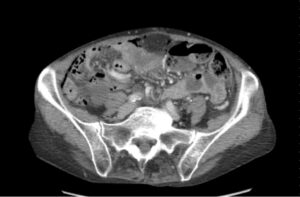

FIGURE 2: Computerized tomography of the abdomen with contrast confirmed pneumoperitoneum and revealed intramural air in the ileum without obvious gastrointestinal perforation. (Click to enlarge.)

Emergency department evaluation did not reveal acute abdomen or signs of peritonitis or sepsis. Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen with contrast confirmed pneumoperitoneum and revealed intramural air in the ileum without obvious gastrointestinal perforation (see Figure 2).2 Surgical consultation was obtained.

Given the patient’s history of partial colectomy and the degree of pneumoperitoneum, the consulting surgeon decided exploratory laparotomy was indicated to rule out occult gastrointestinal perforation. Exploratory laparotomy revealed no evidence of gastrointestinal perforation, peritonitis or other significant pathology. The abdomen was closed, and the patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery.

Discussion

Different proposed theories regarding PCI pathophysiology include: 1) mechanical, 2) pulmonary, 3) bacterial and 4) immune system dysfunction.7-9 The interconnection between these different mechanisms cannot be ignored.

The mechanical theory describes the importance of increased intraluminal pressure that breaches the normal mucosal barrier, leading to enhanced gut permeability and migration of gas from the gastrointestinal cavity into the intestinal wall.3,8

The pulmonary theory describes the significance of underlying lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma and interstitial pneumonia, which can lead to alveolar rupture causing mediastinal emphysema tracking caudally to the retroperitoneum and into the bowel mesentery.3,8

The bacterial theory states that bacteria penetrate the intestinal mucosal wall barrier and produce alpha glucosidase, contributing to flatulence by suppressing carbohydrate absorption in the colon and leading to the generation of gas.3,8

Connective tissue diseases, such as systemic sclerosis (SS) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), have also been postulated to cause intestinal mucosal atrophy and defects within the mucosa leading to the formation of cysts in the intestinal submucosa.9

PCI usually results from an underlying condition, likely due to different pathophysiological processes. Unlike acute gastrointestinal conditions associated with this condition, PCI can be chronic and often asymptomatic.

The pathogenesis of PCI in various rheumatic conditions, however, is unclear. CT imaging is the generally accepted modality to establish a diagnosis of PCI and has greater sensitivity for diagnosis than plain film or ultrasound imaging.2,3

Pneumoperitoneum may be associated with PCI as a benign asymptomatic condition after the rupture of intramural subserosal air-containing cysts without true intestinal wall perforation.2-5 For patients with pneumoperitoneum, a clinical assessment is paramount. If acute pathology is suspected, such as bowel perforation, peritonitis or necrotic bowel, then urgent surgical intervention is warranted.3 In the absence of convincing clinical signs, clinical monitoring is warranted and may save the patient from undergoing an invasive procedure.

Back to the Case

In our patient, a repeat CT scan of the abdomen, obtained six months after the initial scan, revealed continued pneumoperitoneum with no new intra-abdominal pathology. She did not report any new abdominal symptoms. These findings suggest the benign nature of this patient’s pneumoperitoneum. The patient was ultimately lost to follow-up.

This case report illustrates the paramount importance of keeping a high index of suspicion for PCI in patients with underlying connective tissue disease presenting with pneumoperitoneum without signs of an acute intra-abdominal process.

Jagmohan S. Jandu, MD, MA, is an internal medicine physician practicing with the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group (PAFMG) at Palo Alto Medical Foundation (PAMF), Fremont, Calif. He practices in an outpatient primary care clinic setting.

Jagmohan S. Jandu, MD, MA, is an internal medicine physician practicing with the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group (PAFMG) at Palo Alto Medical Foundation (PAMF), Fremont, Calif. He practices in an outpatient primary care clinic setting.

Sri Harsha Boppana, MD, is a first-year rheumatology fellow at Larkin Hospital, Miami. He finished his internal medicine residency at the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine.

Sri Harsha Boppana, MD, is a first-year rheumatology fellow at Larkin Hospital, Miami. He finished his internal medicine residency at the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine.

Prahlad A. Reddy, MD, is a rheumatologist at Arthritis Consultants, Reno, Nev. Dr. Reddy completed his rheumatology fellowship at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

Prahlad A. Reddy, MD, is a rheumatologist at Arthritis Consultants, Reno, Nev. Dr. Reddy completed his rheumatology fellowship at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

Atigadda N. Reddy, MD, FACP, FACG, AGAF, is a retired gastroenterologist and adjunct clinical professor of medicine at the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine.

Atigadda N. Reddy, MD, FACP, FACG, AGAF, is a retired gastroenterologist and adjunct clinical professor of medicine at the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine.

References

- Morrison WJ, Siegelman SS. Pneumatosis intestinalis in association with connective tissue disease. South Med J. 1976 Dec;69(12):1536–1539.

- Braumann C, Menenakos C, Jacobi CA. Pneumatosis intestinalis—A pitfall for surgeons? Scand J Surg. 2005;94(1):47–50.

- St Peter SD, Abbas MA, Kelly KA. The spectrum of pneumatosis intestinalis. Arch Surg. 2003 Jan; 138(1):68–75.

- Knechtle SJ, Davidoff AM, Rice RP. Pneumatosis intestinalis. Surgical management and clinical outcome. Ann Surg. 1990 Aug;212(2):160–165.

- Han BG, Lee JM, Yang JW, et al. Pneumatosis intestinalis associated with immune-suppressive agents in a case of minimal change disease. Yonsei Med J. 2002 Oct;43(5):686–689.

- Hwang J, Reddy VS, Sharp KW. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis with free intraperitoneal air: A case report. Am Surg. 2003 Apr;69(4):346–349.

- Azzaroli F, Turco L, Ceroni L, et al. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. World J Gastroenterol. 2011 Nov 28;17(44):4932–4936.

- Ling F, Guo D, Zhu L. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: A case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019 Nov 6;19(1):176.

- Wang YJ, Wang YM, Zheng YM, et al. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: Six case reports and a review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018 Jun 28;18(1):100.