Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease characterized by noncaseating granulomas in affected tissues, mostly involving the lungs and lymph nodes.1,2 The etiology of sarcoidosis remains unknown but is thought to be due to an inflammatory response to an antigen exposure in genetically predisposed individuals.1 Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF‑α), a pro-inflammatory cytokine, plays an essential role in this inflammatory response leading to the development of granulomas.3 Therapy with TNF-α inhibitors has proved effective for many patients with sarcoidosis.3

Interestingly, some TNF-α inhibitors have been recognized to induce sarcoidosislike disease.4 In 2016, a literature review found 59 cases of sarcoidosis associated with the use of TNF-α inhibitors, with 37 out of 59 associated with etanercept use.5 Fifty-two patients showed partial or complete resolution following discontinuation of the TNF-α inhibitor, either alone or along with steroid administration.

Here, we present a case of a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who developed a sarcoid-like reaction while being treated with etanercept.

Case Presentation

A 29-year-old Black woman with a past medical history of adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was admitted to the emergency department complaining of fever, chills and severe shortness of breath.

Five years prior to this hospitalization—the time of her initial presentation—the patient was admitted to the hospital with fever, pharyngitis, diffuse rash, myalgias, fatigue and a polyarticular arthritis. Laboratory evaluations demonstrated elevated inflammation markers (i.e., erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein), leukocytosis, transaminitis and rheumatoid factor. The creatine kinase was within normal limits, and no anti-nuclear antibodies or anti-citrullinated protein antibodies were detected. A chest X-ray showed no evidence of lymphadenopathy or pulmonary disease.

During the prior hospital admission, a thorough evaluation did not demonstrate evidence of an acute viral, bacterial or fungal infection. She was diagnosed with AOSD based on Yamaguchi classification criteria. She was initially treated with corticosteroids. Because the patient did not respond as anticipated, she was subsequently treated with hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate. Over the following weeks, the patient was also diagnosed with RA based on her positive RF, elevated inflammatory markers and polyarthritis present for greater than six weeks. The rash resolved quickly after diagnosis.

At that earlier time, the primary joints affected were the right third proximal interphalangeal joint and ankles.

During the next 12 months, she was frequently lost to follow-up and took her medications inconsistently.

After one year of therapy with methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine, her rheumatologist initiated 50 mg of subcutaneous etanercept weekly. The response to this treatment was adequate, and she was gradually tapered off methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine. She continued therapy with etanercept for four consecutive years. The patient remained an everyday smoker.

At the time of the current hospital admission, the patient reported that she had gradually developed shortness of breath, subjective fevers and chills over the previous two months. Initially, she was evaluated at a local hospital where a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest without contrast showed multifocal pulmonary infiltrates. Due to her symptoms (fevers, chills and shortness of breath), the patient was immediately started on intravenous antibiotics for possible multifocal pneumonia. She improved slightly, and the patient was discharged home to continue therapy with levofloxacin.

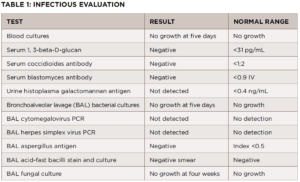

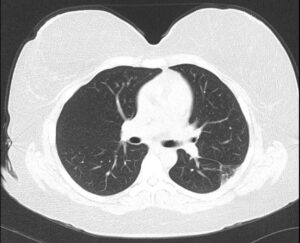

FIGURE 1A: Lung window from computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) of the chest: Bilateral areas of pulmonary consolidation with air bronchograms (arrows).

At home, her clinical situation worsened significantly, and she presented in the emergency department at our hospital. This time, the patient was complaining about left-sided pleuritic chest pain and severe shortness of breath. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 98.4°F, respiratory rate of 18, heart rate of 84 and blood pressure of 127/64. The patient looked mildly distressed, had a nontender chest wall and, despite the CT findings, had clear lung fields. No skin rashes were identified.

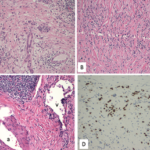

FIGURE 1B: Mediastinal window from CTPA showing bilateral hilar (arrowheads) and subcarinal (arrow) adenopathy. No evidence of pulmonary embolism was found (not shown).

The laboratory analysis demonstrated a white blood cell count of 10 k/mcL and a procalcitonin of <0.05 ng/mL. A CT pulmonary angiogram was requested and showed bilateral areas of pulmonary consolidation with air bronchograms, as well as bilateral hilar and subcarinal adenopathy (see Figures 1A and 1B). Despite the use of antibiotics, no improvement was noted.

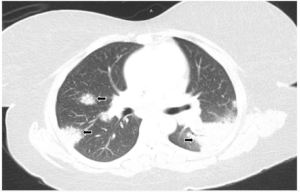

We requested a consultation with a pulmonologist. Bronchoscopy showed no endobronchial lesions. Further, bronchial brushing cytology was negative for malignancy. A transbronchial biopsy of the pulmonary parenchyma was obtained and demonstrated non-necrotizing granulomas.

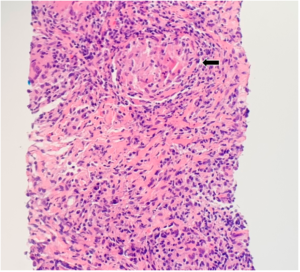

Further evaluation did not demonstrate evidence of a bacterial, viral or fungal infection (see Table 1). The antibiotic treatment was stopped. A follow-up chest X-ray was obtained four weeks later and showed no improvement in pulmonary infiltrates. A CT-guided core lung biopsy was performed to rule out cryptogenic organizing pneumonia; it again demonstrated non-necrotizing granulomas consistent with sarcoidosis (see Figure 2).

Reviewing the patient’s history, including the previous diagnoses (i.e., AOSD and RA) and prior treatments, we became concerned her condition might be a sarcoid-like reaction induced by a medication.

FIGURE 2: CT-guided lung biopsy specimen demonstrating non-necrotizing granuloma (arrow; magnification 100x).

Reviewing the literature, we found a few case reports linking etanercept to new-onset sarcoidosis. Subsequently, we discontinued etanercept for our patient. Treatment with prednisone was initiated, at a dose of 1 mg/kg, which was gradually tapered over the course of eight weeks.

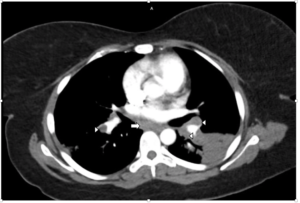

Six weeks after receiving the corticosteroid treatment, the patient presented to follow-up, feeling much improved. A chest X-ray showed near-complete resolution of the left upper lung density, with residual opacity remaining. Six months after this admission, the patient reported complete resolution of her clinical symptoms. CT of the chest revealed complete resolution of bilateral pulmonary infiltrates with minimal left upper lobe scar (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3: Six-month follow-up CT of the chest without contrast: Resolution of bilateral pulmonary infiltrates with minimal left upper lobe scar.

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a chronic systemic granulomatous disease of unknown etiology.1 The disorder most commonly affects the lungs and lymph nodes, but can involve any organ system.2 In more than 90% of affected patients, intrathoracic involvement can be seen, typically presenting as lymphadenopathy and interstitial lung disease.6 Nonspecific constitutional manifestations may occur, such as fever, fatigue, malaise and weight loss.1 Respiratory symptoms include cough, shortness of breath and pleurisy.7

The diagnosis is established when the following three criteria are present: compatible clinical and radiographic findings, histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas and exclusion of other diseases.8

Sarcoidosis is thought to result from exposure to an unidentified antigen in a genetically predisposed host that leads to an inflammatory response composed of activated macrophages and T lymphocytes.1 These cells produce a pattern of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 2, interferon-γ and TNF-α.1 The production of TNF-α from alveolar macrophages participates in the induction and maintenance of granuloma formation.3 Due to the essential role of TNF-α in the disease’s pathogenesis, TNF-α antagonists are considered part of the treatment of sarcoidosis.3

Paradoxically, several documented cases of sarcoidosis are associated with the use of TNF-α inhibitors, including neurosarcoidosis, cutaneous sarcoidosis and pulmonary sarcoidosis.9-12 The pathophysiology of TNF-α inhibitor-induced sarcoid-like reactions is not entirely understood, but several potential mechanisms have been proposed. It has been suggested that TNF-α suppression can lead to cytokine imbalance, thereby leading to granulomatous inflammation.13 Also, peripheral TNF-α antagonism may activate autoreactive T cells, inducing the formation of granulomas.14

Some research suggests that sarcoidosis may stem from a response to an infectious antigen. Mycobacteria and Cutibacteria (formerly Propionibacteria) are the most common of several identified organisms whose DNA and proteins have been identified in sarcoidosis.15 It is, therefore, possible that immune suppression by TNF-α inhibitor therapy results in the proliferation of an infectious organism, which results in noncaseating granuloma formation.13

Interestingly, most sarcoidosis cases associated with TNF-α inhibitors have been attributed to etanercept.5 Also, etanercept has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of sarcoidosis and might actually worsen the disease.16 One hypothesis suggests that this relationship might be related to etanercept’s mechanism of action. Infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antibodies that strongly and irreversibly bind to both soluble and transmembrane TNF-α molecules. Conversely, etanercept is a soluble TNF-α receptor that weakly and reversibly binds to the soluble TNF-α molecule and, thus, it has less biological activity.5,17 Further, etanercept has been shown to increase T cell synthesis of interferon-γ, which is an essential player in granuloma formation.11

Sarcoidosis associated with TNF-α inhibitors is reversible in most cases. Decock et al. reported that discontinuation of TNF inhibitors alone has led to an improvement in 86% of cases, and TNF inhibitor discontinuation with the addition of steroids led to improvement or resolution in 95% of cases.12

One could argue that the patient in this case might have had sarcoidosis initially and was misdiagnosed with RA and AOSD. However, the absence of clinical manifestations of sarcoidosis, such as lymphadenopathy, erythema nodosum and ocular involvement, and normal chest radiograph at the time of initial diagnosis may argue against that.

The other consideration, and most supported by the authors, is that the patient had developed an etanercept-induced sarcoid-like reaction. This is supported by the fact that the patient’s clinical improvement was rapid and sustained after the discontinuation of etanercept and the initiation of a short treatment with corticosteroids, with no recurrence of the symptoms after one year.

In Sum

In patients treated with immunosuppressive agents, sarcoidosis can be a challenging diagnosis as many infections can cause similar signs and symptoms. Based on this case, we want to raise awareness that etanercept may be a precipitating factor in the development of sarcoidosis. Further, as reviewed in this report, in such cases, rapid discontinuation of this drug may lead to complete resolution of the clinical symptoms and radiographic findings in a short time.

Luis Lora Garcia, MD, served as chief resident of internal medicine at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati. He currently practices as an internist with Franciscan Physician Network, Michigan City, Ind.

Luis Lora Garcia, MD, served as chief resident of internal medicine at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati. He currently practices as an internist with Franciscan Physician Network, Michigan City, Ind.

Sneha Centala, MD, MS, is chief resident of internal medicine at TriHealth Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati.

Sneha Centala, MD, MS, is chief resident of internal medicine at TriHealth Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati.

Gitanjali Lobo, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Oschner Hospital, New Orleans.

Gitanjali Lobo, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Oschner Hospital, New Orleans.

Shahla Mallick, MD, is a pulmonary/critical care specialist at TriHealth Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati.

Shahla Mallick, MD, is a pulmonary/critical care specialist at TriHealth Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati.

Diana Girnita, MD, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Rheumatology Department at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and founder of the telemedicine company Rheumatologist OnCall, Sunnyvale, Calif.

Diana Girnita, MD, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Rheumatology Department at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and founder of the telemedicine company Rheumatologist OnCall, Sunnyvale, Calif.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Charles Perme, MD, who reviewed and selected the radiological images, and to Megan Smith, MD, who provided the pathology image.

References

- Statement on Sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Aug;160(2):736–755.

- Thomas KW, Hunninghake GW. Sarcoidosis. JAMA. 2003 Jun 25;289(24):3300.

- Callejas-Rubio JL, López-Pérez L, Ortego-Centeno N. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor treatment for sarcoidosis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008 Dec;4(6):1305–1313.

- Massara A, Cavazzini L, La Corte R, Trotta F. Sarcoidosis appearing during anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy: A new ‘class effect’ paradoxical phenomenon. Two case reports and literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Feb;39(4):313–319.

- Sim JK, Lee SY, Shim JJ, Kang KH. Pulmonary sarcoidosis induced by adalimumab: A case report and literature review. Yonsei Med J. 2016 Jan;57(1):272–273.

- Ungprasert P, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of sarcoidosis: An update from a population-based cohort study from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Reumatismo. 2017 May 22;69(1):16–22.

- Wu JJ, Schiff KR. Sarcoidosis. Am Fam Physician. 2004 Jul 15;70(2):312–322.

- Soto-Gomez N, Peters JI, Nambiar AM. Diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis. Am Fam Physician. 2016 May 15;93(10):840–848.

- Durel C-A, Feurer E, Pialat J-B, et al. Etanercept may induce neurosarcoidosis in a patient treated for rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Neurol. 2013 Dec 28;13(1):212.

- Vieira MAHB, Saraiva MIR, da Silva LKL, et al. Development of exclusively cutaneous sarcoidosis in patient with rheumatoid arthritis during treatment with etanercept. Rev Assoc Méd Bras (1992). 2016 Nov;62(8):718–720.

- Gifre L, Ruiz-Esquide V, Xaubet A, et al. Lung sarcoidosis induced by TNF antagonists in rheumatoid arthritis: A case presentation and a literature review. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011 Apr;47(4):208–212.

- Decock A, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, et al. Sarcoidosis-like lesions: Another paradoxical reaction to anti-TNF therapy? J Crohns Colitis. 2017 Mar 1;11(3):378-383.

- van der Stoep D, Braunstahl G-J, van Zeben J, Wouters J. Sarcoidosis during anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy: No relapse after rechallenge. J Rheumatol. 2009 Dec;36(12):2847–2848.

- Bhargava S, Perlman DM, Allen TL, et al. Adalimumab induced pulmonary sarcoid reaction. Respir Med Case Rep. 2013 Oct 26;10:53–55.

- Celada LJ, Hawkins C, Drake WP. The etiologic role of infectious antigens in sarcoidosis pathogenesis. Clin Chest Med. 2015 Dec;36(4):561–568.

- Utz JP, Limper AH, Kalra S, et al. Etanercept for the treatment of stage II and III progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis. Chest. 2003 Jul;124(1):177–185.

- Dinarello CA. Differences between antitumor necrosis factor-alpha monoclonal antibodies and soluble TNF receptors in host defense impairment. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2005 Mar;74:40–47.