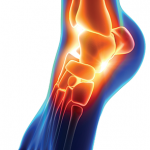

Figure 2: A dorsal view of the right ankle/foot with associated joint inflammation and erythema of the ankle extending into the forefoot.

An examination revealed that he had resolving dactylitis in the left index finger, with tenderness, swelling and warmth in the right wrist extending into the dorsum of right hand, the left ankle and the right ankle extending into the forefoot (see Figures 1 & 2). Passive and active range of motion of the right foot and right wrist elicited mild discomfort. He also had areas of blanching erythema in the right lower extremity extending from the mid tibia area through the dorsum of foot.

He had an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 54 mm/hr, C-reactive protein (CRP) of 30 mg/dL, a serum urate of 2.2 mg/dL. A test for rheumatoid factor was negative, and he had no anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the right foot and ankle prior to consultation revealed a large amount of non-specific dorsal foot swelling, without evidence of a discernible fluid collection (see Figure 3).

Based on the patient’s history, exam, overall clinical picture and the temporal association to his COVID-19 infection, a diagnosis of reactive arthritis was made. Given the lack of improvement despite taking NSAIDs for 10 days, the decision was made to initiate systemic glucocorticoid therapy.

Following the initiation of 30 mg of prednisone daily, the patient had marked improvement in symptoms. Over the next 24–48 hours, the patient’s swelling and inflammation of the left lower extremity and left index finger, and erythematous rash resolved. There was diminished, albeit persistent, swelling of the right hand, right wrist, right foot and ankle, with improved active and passive range of motion. He also had normalization in his white blood cell count.

Given that the patient improved symptomatically, he was discharged home with a steroid taper and plans to follow up with a rheumatologist. Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up upon discharge and has not returned to the rheumatology clinic for re-evaluation.

Figure 3: CT imaging shows a large amount of inflammation and swelling centered on the dorsal midfoot and tenosynovitis without evidence of a discrete drainable fluid collection, soft tissue gas, radiopaque foreign body, osseous erosion or fracture.

Discussion

Reactive arthritis was first described as “an arthritis which developed soon after or during an infection elsewhere in the body, but in which the microorganisms cannot be recovered from the joint.”1

In the U.S., Chlamydia is the most common cause of reactive arthritis. Other common causes include Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Escherichia coli and Campylobacter.2 Traditionally, the most frequently observed infections to precipitate reactive arthritis are bacterial. HIV has been associated with reactive arthritis, but viral etiologies remain few and far between, making the development of reactive arthritis following COVID-19 even more intriguing.3,4

By classification, reactive arthritis falls into a larger collection of diseases known as spondyloarthritis. Other members of this family include ankylosing spondylitis/axial spondyloarthritis, peripheral spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease-associated arthritis and undifferentiated. These diseases often distinguish themselves from other inflammatory joint disease by the presence of such features as enthesitis, dactylitis and axial involvement without specific serologic markers.5

Spondyloarthritis historically shares a strong association with the human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) allele. It is estimated that the prevalence of HLA-B27 in patients with reactive arthritis is up to 50%. Men are affected more often than women, at a rate of 3:1. The condition can occur at any age, but is most common in the third and fourth decades of life.6

Although not entirely understood, the condition is thought to be due to improper activation of the immune system within the synovium through the process of molecular mimicry. From a clinical standpoint, the timing of disease and pattern of joint involvement are critical to establish a diagnosis of reactive arthritis. Generally, the arthritis appears several days or even weeks after the precipitating infection, often in a mono- or oligoarticular pattern with associated enthesitis and dactylitis. Although not exclusively, the lower extremities are often affected.2

From a diagnostic standpoint, there can often be uncertainty about what infection precipitated the inflammation because different organisms can induce the same symptoms.7 In our case, the patient had no symptoms of a sexually transmitted disease or gastrointestinal infection in the preceding weeks. Additionally, PCR testing for both Chlamydia and Gonorrhoeae were negative, as well as the patient’s HIV screen.

Our patient was treated with antibiotics for a complicated parapneumonic effusion he developed following his original traumatic rib fractures and hemothorax. However, our patient’s cultures remained negative. Given that many causative infections for reactive arthritis are bacterial in nature, some have proposed antibiotics as a possible therapy. According to a meta-analysis and review conducted in 2013, antibiotics are not generally indicated for reactive arthritis, aside from when they are necessary to treat an ongoing and underlying causative infection.8

Upon review of our case, it appears our patient’s arthritic symptoms appeared well before his questionable intrathoracic infection was identified.

In general, many cases of reactive arthritis and their associated symptoms resolve spontaneously within six months, and a large majority resolve within one year.9 Depending on the severity of symptoms, treatments are generally focused on reducing inflammation. NSAIDs are often followed by systemic steroids if symptoms persist, such as in our patient.

The initiation of prednisone seemed to quickly improve our patient’s symptoms. Given his symptoms, timing of development and lack of other likely causative infections, it was deemed his reactive arthritis was most likely due to COVID-19.

Upon our literature review, fewer than 10 documented cases of reactive arthritis have followed COVID-19 infection. Overall, musculoskeletal symptoms due to COVID-19 can be common; one study showed that up to 35% of hospitalized patients developed myalgias.10 In addition to myalgia, other studies have noted acute arthralgias and back pain with COVID-19, although very few have demonstrated these symptoms in a time frame consistent with reactive arthritis.11

With the number of COVID-19 cases within the U.S. well into the millions, one could reason that reactive arthritis may be more prevalent and underdiagnosed than we think. With this case, we hope to bring attention to this potential complication of COVID-19 and encourage clinicians to remain diligent in their approach to joint pain particularly in the setting of recent infection and associated rash.

As the medical community continues to grapple with COVID-19, further research is warranted.