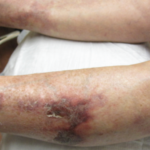

Clinical Presentation & Diagnosis: Clinicians should suspect calciphylaxis when patients present with painful ischemic skin necrosis. In some cases, pain can precede skin lesions. Typical areas involved include the abdomen, thighs and buttocks. These areas typically feature an abundant amount of adipose tissue.1

Calciphylaxis is a clinical diagnosis. Although biopsies can help, they can worsen ulcerations and infections. Sometimes bone scans can help identify soft-tissue calcifications.8,9

Management: To adequately treat calciphylaxis, clinicians must perform an evaluation for reversible calciphylaxis causes. Workups should include checking calcium, phosphate and PTH levels. Also perform a thorough evaluation for malignancies and connective tissue diseases.10

The most widely used therapy is sodium thiosulfate. It’s thought that sodium thiosulfate works by removing calcium through chelation. In animal models, it’s been shown to transiently decrease ionized calcium and increase urinary calcium excretion.11

More than 51 cases of calciphylaxis have been successfully treated. Clinical response typically occurs within one or two weeks, with pain alleviation occurring first and wound healing following up to eight weeks after.12,13

Bisphosphonates have also been used to treat calciphylaxis. In six reported cases, either pamidronate or etidronate were used to treat uremic calciphylaxis. In two reported cases, bisphosphonates successfully treated patients with non-uremic calciphylaxis.14,15,16 Some case reports have shown responses as early as two days post-pamidronate infusion. The exact mechanism of how bisphosphonates reduce calciphylaxis remains unknown, but others have suggested bisphosphonates may inhibit macrophages and thereby suppress inflammatory cytokine release.17 Others have suggested the mechanism of action occurs via inhibition of calcium phosphate crystal formation, which has been implicated in ectopic calcifications.15

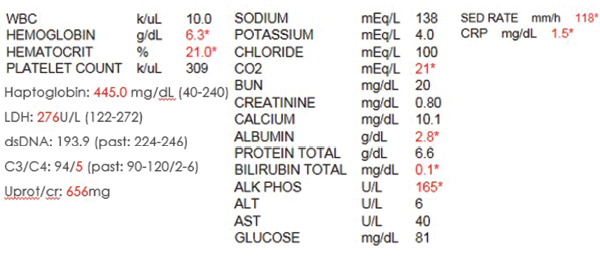

Table 1. The initial laboratory findings.

In patients with hyperparathyroidism, calcimimetics, such as cinacalcet, have shown much success in treating this rare, deadly illness. To date, nine cases of calciphylaxis have been successfully treated with calcimimetics used as an adjunctive therapy.18 Calcimimetics function by increasing calcium receptor sensitivity, thereby decreasing PTH levels.

But remember: Regardless of the above-mentioned treatments, the most important aspect of treating patients with calciphylaxis remains wound management. Due to the high mortality rate associated with the condition secondary to infections, having a wound-care specialist involved early on is crucial. In severe cases, surgical debridement may prove necessary. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has also aided in wound healing. Research suggests hyperbaric oxygen stimulates fibroblast proliferation and neoangiogenesis, promoting arteriolar constriction to prevent tissue reperfusion injuries.19 High concentrations of oxygen are directly toxic to many infectious organisms, which helps prevent wound infections. A recent retrospective study of 46 cases showed 58% of the patients improved with hyperbaric oxygen therapy.20

Conclusion

Calciphylaxis remains poorly understood with poor outcomes. Cases of non-uremic calciphylaxis remain rare. Rarer still are reports of calciphylaxis in patients with an underlying connective tissue disease. Of the cases reviewed of patients with underlying SLE who had calciphylaxis, the majority ended in death due to severe infections.