MOLEKUUL / Science Source

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is an inflammatory rheumatic condition characterized by pain and morning stiffness at the neck, shoulders and hip girdle. It can be associated with giant cell arteritis (GCA); in fact, the two disorders may represent a continuum of the same disease process. This case describes a patient who initially refused treatment for PMR and eventually developed GCA, resulting in multiple complications and requiring four hospitalizations over a yearlong period.

The Case

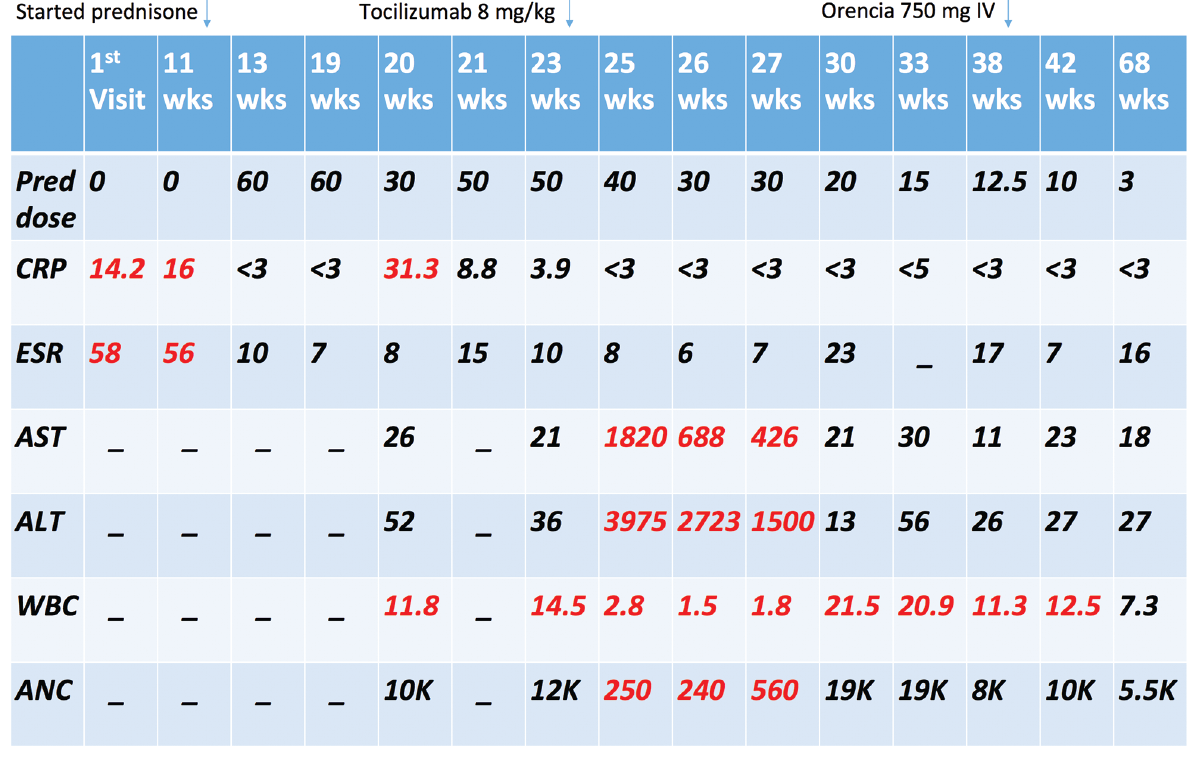

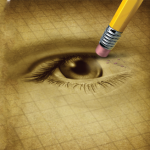

A 79-year-old woman presented to her primary care physician’s office for an annual physical. She described a four-month history of widespread pain, proximal muscle weakness and morning stiffness, most prominent in the neck and shoulders. These symptoms made her work as a hairdresser extremely difficult. Labs showed a normal creatine kinase (CK) of 53 units/L (normal range: 26–192 units/L), an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 58 mm/hr (normal range: <30 mm/hr) and an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) of 14.2 mg/L (normal range: <10 mg/L). She was then referred to our rheumatology clinic for suspected PMR.

At her initial visit with us, she complained of weakness in her bilateral shoulders, thighs and calves, all worse in the morning and improved with activity. She was unable to lift her arms above her shoulders due to pain and stiffness, and had a difficult time getting up from a seated position. She denied fevers, chills, night sweats, anorexia, weight loss, rash, headaches, vision changes, jaw pain/claudication, scalp tenderness or joint swelling.

Her medical history was notable for breast cancer, which was now in remission, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome and hyperlipidemia with a history of statin intolerance. Medications included a fluticasone inhaler twice daily, an albuterol inhaler as needed, and calcium and vitamin D supplements.

She had no family history of autoimmune disease, PMR or vasculitis. Her social history was significant for three to four years of smoking in her 20s and occasional alcohol use. The physical exam was normal, except for limited active abduction of the shoulders.

The patient was advised to start 15 mg of prednisone daily for a suspected diagnosis of PMR, but she refused. She expressed apprehension of taking any prescription medications and was adamant she wanted to “control the inflammation with dietary changes.”

The patient was warned that approximately 15% of patients with PMR develop GCA, which could potentially lead to permanent blindness.1 She was instructed to call our office if she changed her mind regarding starting the prednisone. She was educated about symptoms suggestive of GCA, and was instructed to contact us if she developed any such new symptoms.

Two months later the patient was seen in follow-up. She reported her symptoms had improved on an elimination diet. However, on review of systems, she admitted to a mild right side parietal headache, right side neck pain, right side sinus pain, a vague sensation of jaw tiredness when chewing and mildly blurry vision for two weeks. Labs revealed a CRP of 16 mg/L (normal: <10 mg/L), ESR of 56 mm/hr (normal: <30 mm/hr), a serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) with polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia consistent with chronic inflammation, interleukin (IL) 6 of 13 pg/mL (normal: <5 pg/mL), negative hepatitis serologies and negative QuantiFERON-TB gold. The IgG was 1,600 mg/L, which was at the top range of normal.

Given the high concern for GCA, she agreed to a right temporal artery biopsy, which showed classic giant cell arteritis with transmural (predominantly medial and adventitial) inflammation comprising lymphocytes, plasma cells and multinucleated giant cells, as well as segmental destruction of the internal elastic lamina on H&E and VVG stains.

She was started on 60 mg prednisone daily and 81 mg aspirin daily.

Psychiatric complications of steroid use are seen in about 6% of patients on steroids & seem to be dose dependent; psychosis typically occurs at doses of greater than 20 mg

She was seen in follow-up one week later, and she reported that all of her symptoms—including her myalgias, headache, jaw pain and vision changes—had completely resolved. Her only new complaint was difficulty sleeping, but she declined a sleep aid. Labs showed normalized inflammatory markers. At her next office visit a month later, she was found to be emotionally labile with anxiety, pressured speech, suicidal ideation and episodes of events in which laughing and crying would trigger a loss of muscle tone but not consciousness (this was observed in the exam room). She was admitted to the hospital for management of new-onset, steroid-induced mania, depression, anxiety and cataplexy.

During her hospitalization, her prednisone was quickly weaned to 30 mg/day, but she subsequently developed recurrent symptoms of headache and blurry vision, and her CRP jumped from <3 mg/L to 31.1 mg/L. Her prednisone dose was, therefore, increased to 50 mg daily, and she was started on olanzapine for psychosis and lithium for mood stabilization. Additional steroid-

sparing agents were discussed with the patient and her family, but she adamantly refused treatment with methotrexate (because she knew someone who had side effects to methotrexate), and she wasn’t willing to start any new medication for GCA.

She was evaluated by a neurologist, and a brain MRI showed acute restricted diffusion of the right occiput, likely indicative of a focal infarction. She was evaluated by an ophthalmologist, who saw no evidence of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy on dilated eye exam. Her psychiatric symptoms improved, and she was discharged to a skilled nursing facility on 50 mg prednisone daily, olanzapine, lithium and aspirin.

At her hospital follow-up visit, the patient complained of left lower extremity pain and swelling. Labs showed inflammatory markers had again normalized. A lower extremity venous ultrasound was performed immediately and revealed two distal deep vein thromboses (DVT) in the popliteal and gastrocnemius veins.

We decided to treat the distal DVTs with supportive care and close follow-up given the patient was at high risk for falling and anticoagulation was felt to be unacceptably dangerous.

At that time, the patient and her family agreed to treatment with tocilizumab in an attempt to help further wean her prednisone dose. She received 480 mg IV tocilizumab (8 mg/kg) with plans for monthly dosing.

Seven days after her tocilizumab infusion, she was getting up to go to the bathroom, fell and hit her head. She was evaluated in the emergency department, where basic lab evaluation revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 2.8 K/mL (normal: 3.8–11 K/mL) with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 250 cells/mm3 (normal: 1,500–8,000 cells/mm3), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 1,820 units/L (normal: 15–37 units/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 3,975 units/L (normal: 13–59 units/L), total bilirubin of 1.7 mg/dL (normal: 0.1–1.2 mg/dL) and alkaline phosphatase of 173 units/L (normal: 38–126 units/L).

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further workup and treatment of acute hepatitis and neutropenia. Labs revealed a negative hepatitis viral panel, negative anti-mitochondrial and anti-smooth muscle antibodies and normal CRP and ESR. An abdominal ultrasound showed normal liver echotexture and size. She was treated with supportive care for a diagnosis of drug-induced hepatitis and neutropenia secondary to tocilizumab, and it was recommended the patient never receive tocilizumab again.

During her hospital stay, the patient complained of new, right-side, lower extremity edema. A venous duplex ultrasound showed no DVT, but an incidental finding of acute thrombus in the mid segment of the right popliteal artery extending into the tibial trunk artery was noted. She was evaluated by a vascular surgeon who felt that because the patient was asymptomatic, apart from edema, and without claudication symptoms, no vascular intervention was required. Over the course of a few days, the patient’s ALT trended up to 4,699 units/L and then began to decline; her WBC count trended down to 1.5 K/mL, with ANC of 0 cells/mm3, and then began to trend upward. The patient was again discharged to a skilled nursing facility.

One week after discharge, the patient developed rigors and was evaluated in the emergency department. She was admitted for possible neutropenic sepsis, but no infection was found. During this hospitalization, she had repeat bilateral lower extremity venous Dopplers that showed a new acute right lower extremity DVT, in addition to the known left gastrocnemius and peroneal DVTs. An arterial Doppler showed the right distal popliteal artery was now near occlusion and progressing into the distal peroneal and anterior tibial arteries, and she was, therefore, started on enoxaparin.

Six weeks later the patient developed acute confusion and was again evaluated in the emergency department. She was found to have acute kidney injury with a creatinine of 1.9 mg/dL (baseline: 1.0 mg/dL) and lithium level of 2.0 mmol/L (normal: 0.6–1.2 mmol/L). She was treated for mild lithium toxicity with fluid resuscitation and discontinuation of lithium. Her confusion improved, and her lithium level became undetectable. The patient was started on divalproex sodium for mood stabilization and again discharged to a skilled nursing facility.

At her hospital follow-up visit, the patient’s liver function tests had completely normalized, and she was again offered methotrexate in the hopes of weaning her prednisone dose, but she adamantly refused. She was then offered abatacept as a steroid-sparing agent, and—after initially refusing—she eventually agreed.

Since starting abatacept at 750 mg IV monthly approximately six months ago she has done very well, experiencing no further complications or hospitalizations. She remains asymptomatic, with normal inflammatory markers, and her prednisone dose has, thus far, been successfully tapered to 3 mg daily. Her psychiatric medications have all been discontinued, and she has remained free of any psychiatric symptoms.

Discussion

This case highlights multiple complications due to the treatments used for GCA and the disease itself. The patient developed steroid-induced mania/psychosis after starting high-dose steroids.

Psychiatric complications of steroid use are seen in about 6% of patients on steroids and seem to be dose dependent; psychosis typically occurs at doses of greater than 20 mg prednisone per day. Psychiatric symptoms are reversible 90% of the time, with discontinuation of steroids.2 Unfortunately, we were unable to wean this patient’s prednisone due to a relapse in her GCA symptoms and rising inflammatory markers; she was, therefore, started on lithium for mood stabilization and later developed lithium toxicity.

We decided to treat the patient with tocilizumab based on a randomized controlled trial published in 2017 that showed GCA patients treated with weekly tocilizumab in addition to a prednisone taper were three times more likely to achieve sustained remission after one year of treatment when compared with patients using a prednisone taper alone; and the cumulative prednisone dose in the tocilizumab group was almost half that of the prednisone-alone groups.3

The approved dosing of tocilizumab for GCA is 162 mg administered subcutaneously every week; however, for both cost and adherence reasons, we elected to treat her with IV tocilizumab. We used the higher dose of 8 mg/kg rather than 4 mg/kg in hopes of enhancing the steroid-sparing effect, because she was having severe steroid side effects.

It should be noted that IV tocilizumab is FDA approved thus far only for rheumatoid arthritis. The recommended monitoring parameters for tocilizumab are to check neutrophils, platelets and ALT/AST prior to therapy and again at four to eight weeks after the start of therapy, and every three months thereafter.

Well-recognized adverse effects of tocilizumab include mild transaminitis in up to 36% of patients, with severe transaminitis occurring only 1–2% of the time, in addition to mild neutropenia in up to 7% of patients. Our patient’s labs were incidentally checked one week after she received tocilizumab, and she was found to have severe grade 4 transaminitis (in the 4,000s) and severe grade 4 neutropenia with an ANC of 0, requiring hospitalization and discontinuation of tocilizumab.

During the patient’s hospitalization, an arterial thrombus was unexpectedly found on venous Doppler. The patient also experienced other thrombotic phenomena, including an acute cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and recurrent lower extremity DVTs. GCA has been shown to increase the risk of CVA, myocardial infarction (MI) and peripheral vascular disease (PVD).4

A study published in Arthritis & Rheumatism by Schmidt et al. examined 33 patients with newly diagnosed GCA using ultrasound exams of the abdominal aorta and 15 peripheral arteries and revealed that 30% had characteristic findings of inflammation (hypoechoic wall thickening or halo sign) in arteries other than the temporal arteries and 12% had abnormalities in the arteries of the lower extremities.5

A study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology by Blockmans et al. performed 18F fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scans on 35 patients with GCA and found vascular FDG uptake in 83%. The most common site of FDG uptake was in the subclavian arteries (74%), while lower extremity uptake was noted in 37%.6 In our case, the patient’s hypercoagulable state was multifactorial; immobilization and recurrent hospitalizations likely played a role in her recurrent DVTs. The patient’s CVA and arterial thrombus may have been directly caused by smoldering inflammation from GCA.

We decided to treat the patient with abatacept based on a randomized controlled trial published in Arthritis & Rheumatism by Langford et al. that showed improvement in the ability to wean prednisone in GCA patients treated with abatacept.7 Fortunately, this has allowed us to wean the patient’s prednisone to 3 mg daily without recurrent symptoms or further complications.

In retrospect, it is tempting to wonder if this patient’s GCA and the complications of both GCA and its treatments might have been avoided if the patient had initially accepted treatment of her PMR with low-dose steroids. It would be unfortunate if her fear of medications actually resulted in the need to use even more medications. However, this is purely speculative, because we could find no data to support the theory that treating PMR early in its course might prevent the later development of GCA. Perhaps this could be an area of future study in the form of a retrospective case series, because a prospective study randomizing patients to delay treatment of PMR would be unethical.

Erin Kenney Hammett, DO, is a rheumatologist at Sansum Clinic, Santa Barbara, Calif.

Erin Kenney Hammett, DO, is a rheumatologist at Sansum Clinic, Santa Barbara, Calif.

Edward Skol, MD, is a rheumatology attending at Scripps Clinic/Scripps Green Hospital La Jolla, Calif. He completed his internal medicine residency at Scripps Mercy Hospital and rheumatology fellowship at Scripps Clinic/Scripps Green Hospital.

Edward Skol, MD, is a rheumatology attending at Scripps Clinic/Scripps Green Hospital La Jolla, Calif. He completed his internal medicine residency at Scripps Mercy Hospital and rheumatology fellowship at Scripps Clinic/Scripps Green Hospital.

References

- Salvarani C, Cantini F, Hunder GG. Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant-cell arteritis. Lancet. 2008 Jul 19;372(9634):234–245.

- Kershner P, Wang-Cheng R. Psychiatric side effects of steroid therapy. Psychosomatics. 1989 Spring;30(2):135–139.

- Stone JH, Tuckwell K, Dimonaco S, et al. Trial of tocilizumab in giant-cell arteritis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 27;377(4):317–328.

- Tomasson G, Peloquin C, Mohammad A, et al. Risk for cardiovascular disease early and late after a diagnosis of giant-cell arteritis: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Jan 21;160(2):73–80.

- Schmidt WA, Natusch A, Möller DE, et al. Involvement of peripheral arteries in giant cell arteritis: A color Doppler sonography study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002 May–Jun;20(3):309–318.

- Blockmans D, de Ceuninck L, Vanderschueren S, et al. Repetitive 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in giant cell arteritis: A prospective study of 35 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Feb;55(1):131–137.

- Langford CA, Cuthbertson D, Ytterberg SR, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial of abatacept (CTLA-4Ig) for the treatment of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Apr;69(4):837–845.