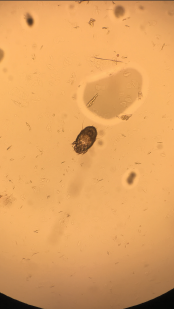

Image 4: A skin scraping turned up scabies.

Persistent eosinophilia, positive pANCA, elevated inflammatory markers and worsening rash led to request for rheumatology consultation. Her first words on meeting me were, “Please, help me with this itching.” She discussed her Internet investigation, which had made her concerned about the kissing bug disease entering her home via China-made furniture. We discussed her trip to Napa Valley and her love for traveling, as well as her inability to travel long distance due to worsening lung function.

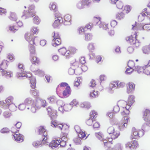

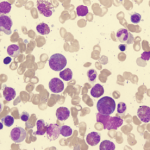

We examined the diffuse morbilliform rash (see Images 1, 2 and 3, below). While working through my imaginary history checkboxes, We questioned her regarding pertinent family history. She stated that although she didn’t have a family history of any autoimmune disorders, her son and daughter-in-law had developed localized rashes since they moved in with her. They had been evaluated by dermatology and allergy/immunology specialists, but were not given a definite diagnosis. Unable to find a unifying diagnosis, we requested a meeting with the patient’s son and daughter-in-law the next morning.

The next day, the patient’s son and daughter-in-law met us in the patient’s room (both clearly upset at having to miss the day’s work because of some doctors’ unusual request). They confirmed the history provided by the patient so far and reported having a skin biopsy with a finding of allergic dermatitis. The patient’s daughter-in-law reported a pruritic lesion on her lower back. Upon examining the rash on her lower back, we looked at each other, nodding in silent affirmation of the diagnosis. Burrows on her lower back gave away the perpetrator, which a skin scraping confirmed to be scabies (see Image 4).

The patient and her family members were treated with ivermectin and permethrin 5% cream due to the severity of the symptoms. All three showed good clinical improvement.

Discussion

Evaluation of patients with eosinophilic disorders requires a detailed assessment for possible allergic, malignant, infectious or autoimmune etiology. Peripheral blood eosinophil count often does not represent the tissue damage. Hence, the first step in evaluation should be to determine if there is any end-organ damage, because life-threatening complications of HE may require immediate empirical intervention.

Dermatologic features are components of almost all HES variants, which often make them unhelpful in diagnosis. Cutaneous lesions can be characterized by edema, eczema, mucosal ulcers, vasculitis, blisters and fibrosis.5 Infectious diseases can present with HE and are often difficult to differentiate from other etiologies. Strongyloides can present decades after initial infection, with eosinophilia as the only indication for subclinical infection. Other possible parasitic HE etiology includes toxocariasis, trichinellosis, hookworm, filariasis and schistosomiasis. Some pathogens responsible for travelers’ diarrhea, such as dientamoeba fragilis, isospora belli and sarcocystis species, can cause eosinophilia. Fungal infections, such as aspergillosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis and coccidiomycosis, often feature associated eosinophilia.