Eosinophilia is usually defined as an eosinophil count of more than 500/microL in peripheral blood.1 An eosinophil count of more than 1,500 is referred to as hypereosinophilia (HE); hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is defined as HE associated with organ dysfunction attributable to eosinophilia.2

Eosinophilia can occur due to infectious, malignancy, autoimmune or allergic etiologies. However, a significant number of patients do not have any identifiable etiology and are classified as idiopathic hypereosinophilic disorder, or hypereosinophilic disorder of unknown significance when there’s no end organ involvement.

Numerous stem cell mutations have been proposed to be associated with primary/idiopathic HE conditions.3,4 Heterogeneity of eosinophilic disorders can often make diagnosis challenging.

Below, we present a case of hypereosinophilic disorder that underscores the importance of detailed history and physical examination in the evaluation of hypereosinophilia.

Case Presentation

A 76-year-old Caucasian woman was admitted to our tertiary care hospital with diffuse pruritic morbilliform rash and progressive worsening of shortness of breath for six months. The rash onset was preceded by a trip to Napa Valley, Calif., and a prolonged course of upper respiratory tract infection. The patient’s past medical history was significant for childhood onset stable asthma and a recent diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with chronic smoking.

Prior to admission, her work-up revealed an eosinophil count of 700/microL (normal = 0–400/microL), C-reactive protein (CRP) at 9.7 mg/L (normal = 0–4.9 mg/L), a sedimentation rate (ESR) of 37 mm/HR, an anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) level of 1:320 titer in nucleolar pattern (normal = <1:160 titer), a cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody level of 38 units (normal = 0–19 units), positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic (pANCA) titer of 1:80 (normal = <1:20) and ), negative anti-myeloperoxidase antibody (anti-MPO). She underwent two skin biopsies prior to hospital admission, both suggestive of allergic contact dermatitis. She had tried a moderate dose of prednisone with minimal symptom relief.

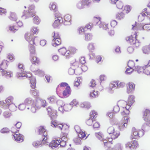

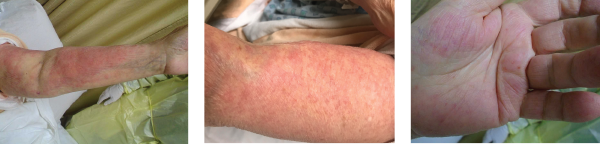

Images 1, 2 & 3: The patient’s examination revealed a diffuse morbilliform rash.

She was advised to consult with an infectious disease consultant for evaluation of a persistent rash, peripheral eosinophilia and dyspnea on exertion. At the time of infectious disease consultation, her rash had continued to worsen, and she was hypoxemic. Therefore, hospital admission was recommended.

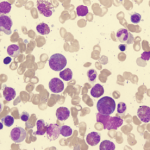

At the time of hospital admission, the patient’s eosinophil count measured 2,200/uL, and her immunoglobulin E was within normal limits. (She was not on prednisone because a bone-marrow biopsy was planned. She was started on prednisone following the biopsy, which reduced her eosinophil count to 700/uL.) During hospitalization, an extensive workup included blood cultures, Toxocara serology, Coccioides serology, Aspergillosis serology, ova and parasite examination of stool (serology was requested), and an enteric parasite panel by PCR—all of which proved unremarkable. The patient underwent a hip X-ray for hip pain, and it revealed soft tissue calcifications in her left proximal femur. A computed tomography (CT) of her pelvis was performed to further evaluate the lesions seen in X-ray; the imaging suggested circumscribed calcification in the vastus lateralis muscle and atrophic uterus. An echocardiogram revealed normal cardiac function.

Some pathogens responsible for travelers’ diarrhea, such as dientamoeba fragilis, isospora belli & sarcocystis species, can cause eosinophilia. Fungal infections, such as aspergillosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis & coccidiomycosis, often feature associated eosinophilia.

Bone marrow biopsy was also requested to evaluate for myeloproliferative or lymphocytic etiologies for HES, and it showed normocellular marrow with maturing trilineage hematopoiesis. Flow cytometric analysis performed on a single cell suspension prepared from bone marrow aspirate revealed no monoclonal B cell population or aberrant T cell phenotype. Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was negative for a deletion at 4q12 (including CHIC2) and for fusion of the FIP1L1 and PDGFRA genes, a rearrangement involving PDGFRB, or a BCR/ABL1 rearrangement.

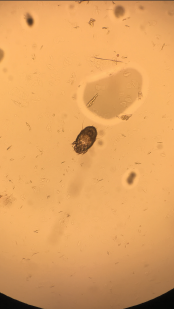

Image 4: A skin scraping turned up scabies.

Persistent eosinophilia, positive pANCA, elevated inflammatory markers and worsening rash led to request for rheumatology consultation. Her first words on meeting me were, “Please, help me with this itching.” She discussed her Internet investigation, which had made her concerned about the kissing bug disease entering her home via China-made furniture. We discussed her trip to Napa Valley and her love for traveling, as well as her inability to travel long distance due to worsening lung function.

We examined the diffuse morbilliform rash (see Images 1, 2 and 3, below). While working through my imaginary history checkboxes, We questioned her regarding pertinent family history. She stated that although she didn’t have a family history of any autoimmune disorders, her son and daughter-in-law had developed localized rashes since they moved in with her. They had been evaluated by dermatology and allergy/immunology specialists, but were not given a definite diagnosis. Unable to find a unifying diagnosis, we requested a meeting with the patient’s son and daughter-in-law the next morning.

The next day, the patient’s son and daughter-in-law met us in the patient’s room (both clearly upset at having to miss the day’s work because of some doctors’ unusual request). They confirmed the history provided by the patient so far and reported having a skin biopsy with a finding of allergic dermatitis. The patient’s daughter-in-law reported a pruritic lesion on her lower back. Upon examining the rash on her lower back, we looked at each other, nodding in silent affirmation of the diagnosis. Burrows on her lower back gave away the perpetrator, which a skin scraping confirmed to be scabies (see Image 4).

The patient and her family members were treated with ivermectin and permethrin 5% cream due to the severity of the symptoms. All three showed good clinical improvement.

Discussion

Evaluation of patients with eosinophilic disorders requires a detailed assessment for possible allergic, malignant, infectious or autoimmune etiology. Peripheral blood eosinophil count often does not represent the tissue damage. Hence, the first step in evaluation should be to determine if there is any end-organ damage, because life-threatening complications of HE may require immediate empirical intervention.

Dermatologic features are components of almost all HES variants, which often make them unhelpful in diagnosis. Cutaneous lesions can be characterized by edema, eczema, mucosal ulcers, vasculitis, blisters and fibrosis.5 Infectious diseases can present with HE and are often difficult to differentiate from other etiologies. Strongyloides can present decades after initial infection, with eosinophilia as the only indication for subclinical infection. Other possible parasitic HE etiology includes toxocariasis, trichinellosis, hookworm, filariasis and schistosomiasis. Some pathogens responsible for travelers’ diarrhea, such as dientamoeba fragilis, isospora belli and sarcocystis species, can cause eosinophilia. Fungal infections, such as aspergillosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis and coccidiomycosis, often feature associated eosinophilia.

Eosinophilia is uncommon in classic scabies, but has been reported in crusted scabies.6 Crusted scabies is more commonly seen in immunocompromised patients, but can appear in an immunocompetent host; such conditions usually require systemic therapy.7

Topical permethrin and oral ivermectin remain the most commonly used scabies medications in the U.S., with topical permethrin being most efficacious.8 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends combination therapy for crusted scabies, either 5% benzyl benzoate or 5% permethrin applied daily for seven days, then twice weekly until cure, and oral ivermectin on days 1, 2, 8, 9 and 15. Consider prescribing additional ivermectin on days 22 and 29 with severe cases.9

In our patient, the scabies diagnosis was delayed, partially due to the presence of multiple autoantibodies. Autoantibodies can be nonspecific and may lead to delayed or wrong diagnosis. ANA can be detected in 5–32% of healthy volunteers, depending on the method and ideal initial dilution cutoff for the performing laboratory.10 It can prove difficult to distinguish between ANA and pANCA on immunofluorescence, giving false-positive pANCA result in patients with positive ANA.

ANCA can appear in vasculitis, infections, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune hepatitis, etc. In a cross-sectional study, 856 consecutive patients tested for ANCA by immunofluorescence were evaluated for underlying diagnosis; cANCA and pANCA were found to have positive predictive values of 51% and 38%, respectively.11 ELISA tests for ANCA-associated vasculitis offer better positive predictive value. Our patient had positive pANCA, but negative anti-MPO antibody.

Patients presenting with eosinophilia can prove truly challenging. If a patient indeed has HES, it can be classified in six main subtypes, which assists in determining the felicitous approach to the treatment:

- Myeloproliferative HE/HES;

- Lymphocytic variant HE/HES;

- Overlap HES or eosinophilic disease restricted to a single organ system;

- Associated HE/HES or HE/HES in the setting of a distinct diagnosis;

- Familial HE/HES; and

- Idiopathic HES.12

These diagnoses can have variable presentations and are often challenging to diagnose and treat. Bottom line: Keep infectious etiologies in the differential while evaluating eosinophilia patients.

Conclusion

This consult experience underscores the importance of detailed history, physical examination and looking beyond the laboratory investigations and imaging studies. Eosinophilic disorders are among the most challenging cases, and our experience can serve as a reminder to keep common infectious causes in the differential diagnosis while evaluating patients.

Vivek R. Mehta, MBBS, is a fellow in the Department of Rheumatology at the Albany Medical Center in Albany, N.Y.

Vivek R. Mehta, MBBS, is a fellow in the Department of Rheumatology at the Albany Medical Center in Albany, N.Y.

Sukhraj Singh, MD, is a hospitalist/internist at the Albany Medical Center.

Sukhraj Singh, MD, is a hospitalist/internist at the Albany Medical Center.

Shubhasree Banerjee, MD, is a clinical assistant professor at the Department of Rheumatology at the Albany Medical Center.

Shubhasree Banerjee, MD, is a clinical assistant professor at the Department of Rheumatology at the Albany Medical Center.

Ruben Peredo-Wende, MD, is an assistant professor, chief and program director of rheumatology at the Albany Medical College.

Ruben Peredo-Wende, MD, is an assistant professor, chief and program director of rheumatology at the Albany Medical College.

References

- Roufosse F, Weller PF. Practical approach to the patient with hypereosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Jul;126(1):39–44.

- Valent P, Klion AD, Rosenwasser LJ, et al. ICON: Eosinophil Disorders. World Allergy Organ J. 2012 Dec;5(12):174–181.

- Lee JS, Seo H, Im K, et al. Idiopathic hypereosinophilia is clonal disorder? Clonality identified by targeted sequencing. PloS One. 2017 Oct 31;12(10):e0185602.

- Pardanani A, Lasho T, Wassie E, et al. Predictors of survival in WHO-defined hypereosinophilic syndrome and idiopathic hypereosinophilia and the role of next-generation sequencing. Leukemia. 2016 Sep;30(9):1924–1926.

- Leiferman KM, Gleich GJ, Peters MS. Dermatologic manifestations of the hypereosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007 Aug;27(3):415–441.

- Van Neste D, Lachapelle JM. Host-parasite relationships in hyperkeratotic (Norwegian) scabies: pathological and immunological findings. Br J Dermatol. 1981 Dec;105(6):667–678.

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: Clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005 Jun;50(5):375–381.

- Strong M, Johnstone P. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD000320.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015 Jun 5;64(RR-03):1–137.

- Mahler M, Ngo JT, Schulte-Pelkum J, et al. Limited reliability of the indirect immunofluorescence technique for the detection of anti-Rib-P antibodies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(6):R131.

- Stone JH, Talor M, Stebbing J, et al. Test characteristics of immunofluorescence and ELISA tests in 856 consecutive patients with possible ANCA-associated conditions. Arthritis Care Res. 2000 Dec;13(6):424–434.

- Klion AD. Eosinophilia: A pragmatic approach to diagnosis and treatment. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:92–97.