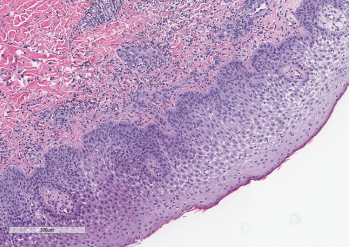

Figure 3: A punch biopsy demonstrated subepidermal edema overlying a dense neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis and epidermis. Courtesy Sandra Haddad, MD

Classic Sweet syndrome comprises most cases of Sweet syndrome and is often associated with infections, autoimmune diseases and inflammatory disorders.1 Diagnostic criteria for classic Sweet syndrome were initially presented by Su and Liu in 1986 and modified by von den Driesch in 1994.2,3 Diagnosis of classic Sweet syndrome is based on meeting both major criteria and two of the four minor criteria, as listed in Table 1. Our patient met both major criteria and all the minor criteria for a diagnosis of classic Sweet syndrome.

Table 1: Criteria for Diagnosis of Classic Sweet Syndrome

| Major Criteria | Minor Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Abrupt onset of tender or painful erythematous plaques or nodules, occasionally with vesicles, pustules or blisters 2. Evidence of dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology | 1. Fever >38ºC 2. Association with inflammatory disease or pregnancy or recent history of upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection 3. 3 out of 4 abnormal lab values at presentation a. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >20 mm/h b. Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) c. >8,000 leukocytes per μL d. >70% neutrophils 4. Response to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids |

Adapted from von den Driesch3

This case provides several learning points. The first point is the association of Sweet syndrome with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Classic Sweet syndrome has been reported as a rare extracutaneous manifestation in patients with IBD. Most of these cases have been reported in women and are associated with colonic disease.4,5 Further, it has been associated with active disease in up to 80% of patients.4,6

Patients who develop Sweet syndrome-associated IBD have more frequent extraintestinal manifestations of IBD, with one case report citing 77% of patients developing an extraintestinal manifestation.6 Sweet syndrome can present at any time in patients with IBD, with 21% of patients developing Sweet syndrome prior to a diagnosis of IBD.6

A second learning point is that any organ system can be involved in Sweet syndrome.7 One challenging aspect of this case was the numerous organ systems affected by Sweet syndrome. Our patient not only had skin and musculoskeletal involvement, but also demonstrated involvement of her lungs and splenic abscesses of impressive size. Given her daily high-grade fevers and abscesses seen in multiple organs on imaging, our gravest concern was an underlying infection. However, despite extensive treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics, her symptoms did not improve. Further, no organisms were identified despite sampling different fluid collections in multiple organs.

Our patient responded very well to corticosteroids, with complete resolution of multi-organ abscesses.

Arthritis, along with other musculoskeletal manifestations, have been reported in up to 59% of cases of Sweet syndrome.8 The arthritis is migratory, asymmetric, non‑deforming and involves at least two joints.8,9 The knees and wrists are reportedly the most frequently affected, followed by ankles, elbows and fingers.9 This arthritis improves with treatment of the underlying disorder.9

In Sum

We have described an unusual case of Sweet syndrome as the initial presentation of Crohn’s disease in a patient who presented with bullous skin lesions, splenic cysts, acute arthritis and an intraosseous calcaneal lesion. Sweet syndrome should be considered for patients presenting with joint pain in the setting of fevers and a new rash. Further, physicians should consider evaluating for possible autoimmune diseases to determine the underlying cause of Sweet syndrome.

In our case, the patient’s reported episode of hematochezia prompted a colonoscopy, which led to a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease as the underlying cause of Sweet syndrome, permitting the patient to receive appropriate treatment and recover in a timely manner.

Ryan Guerrettaz, MD, is an internal medicine-pediatrics resident, PGY-3, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Ryan Guerrettaz, MD, is an internal medicine-pediatrics resident, PGY-3, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Angelo Ciliberti, MD, is a rheumatology fellow, PGY-5, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Angelo Ciliberti, MD, is a rheumatology fellow, PGY-5, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Rochella A. Ostrowski, MD, MS, is an associate professor and rheumatology fellowship program director, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill., and Edward Hines Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital, Hines, Ill.

Rochella A. Ostrowski, MD, MS, is an associate professor and rheumatology fellowship program director, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill., and Edward Hines Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital, Hines, Ill.

Elise Wolff, DO, is a clinical instructor at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Elise Wolff, DO, is a clinical instructor at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Nadia K Qureshi, MD, is associate professor of pediatrics at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Nadia K Qureshi, MD, is associate professor of pediatrics at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Ramzan Shahid, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Ramzan Shahid, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sandra Haddad, MD, of the pathology service of Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill., for the contribution of Figure 3.

References

- Heath MS, Ortega-Loayza AG. Insights into the pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019 Mar 12;10:414.

- Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986 Mar; 37(3):167–174.

- von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994 Oct;31(4):535–556.

- Díaz-Peromingo JA, García-Suárez F, Sánchez-Leira J, Saborido-Froján J. Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with acute ulcerative colitis: Presentation of a case and review of the literature. Yale J Biol Med. May–Jun 2001;74(3):165–168.

- Ali M, Duerksen DR. Ulcerative colitis and Sweet’s syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008 Mar;22(3):296–298.

- Travis S, Innes N, Davies MG, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: An unusual cutaneous feature of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. The South West Gastroenterology Group. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997 Jul;9(7):715–720.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: A review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003 Oct;42(10):761–778.

- Nolla JM, Juanola X, Valverde J, et al. Arthritis in acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome). Ann Rheum Dis. 1990 Feb;49(2):135.

- Moreland LW, Brick JE, Kovach RE, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome): A review of the literature with emphasis on musculoskeletal manifestations. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1988 Feb;17(3):143–153.