Figure 1. At her initial evaluation, the patient presented with a bullous lesion on her left foot.

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, or Sweet syndrome, is an inflammatory disease that classically presents with fever, leukocytosis and tender, erythematous plaques characterized by neutrophilic infiltrates on biopsy. Sweet syndrome has been reported in association with several autoimmune diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematous, rheumatoid arthritis and sarcoidosis.1 Here, we discuss a case of Sweet syndrome as the initial presentation of Crohn’s disease, manifesting with bullous skin lesions, splenic cysts, acute arthritis and an intraosseous calcaneal lesion.

Case Presentation

An 18-year-old woman was transferred to our institution for evaluation of persistent fevers and polyarticular arthritis that began 10 days prior to transfer. Symptoms began with pain in her bilateral ankles and associated blisters on the lateral malleoli. She then developed swelling in her feet, with fixed internal rotation, and was evaluated at a local hospital due to the inability to bear weight.

She was admitted to a hospital when she presented with this pain and night sweats, and was found to be febrile. Subsequently, she developed right hand pain and swelling. Prior to admission, she was otherwise healthy but reported three episodes of abdominal pain with hematochezia, the first occurring two months prior to admission. She reported unintentional weight loss of 10 lbs., dyspnea with rest and exertion, and 10 days of abdominal pain.

On physical exam, her vital signs included a temperature of 102.4º F, a heart rate of 112 beats per minute, and her blood pressure and oxygen saturation were within normal parameters. The musculoskeletal exam was notable for pitting edema of her right hand. Scattered metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints were tender without obvious synovitis, but the joint exam was impaired by the presence of edema.

She also had pitting edema in both feet, which were diffusely tender to palpation (see Figure 1). Both feet were internally rotated, and her range of motion at the ankles was limited by pain. Large bullae were present on both lateral malleoli, with purulent drainage from the lesion on the left lateral malleolus. The patient was tender to palpation at the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. The remainder of her exam was unremarkable.

Laboratory results revealed a leukocytosis of 19.4 K/μL with 81% granulocytes (reference range [RR]: 3.5–10.5 K/μL) and thrombocytosis of 810 K/μL (RR: 150–400 K/μL), C-reactive protein (CRP) of 287.5 mg/L (RR: <8.1 mg/L) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 102 mm/hr (RR: 0–20 mm/hr). Basic metabolic panel and liver function tests were unremarkable.

Laboratory testing was remarkable for the presence of an atypical anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). Tests for rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, anti-nuclear antibody, antibodies against extractable nuclear antigens and anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid antibody were negative. An extensive infectious evaluation for bacterial, viral, fungal and mycobacterial etiologies, including cultures of the bullous skin lesions, was negative. Both a transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiogram were negative for vegetations.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of her chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed a left, lower lobe consolidation in her lung with a large left pleural effusion, and splenomegaly with numerous large cystic lesions. The largest splenic lesion was a partially septated, fluid-filled lesion that measured 9.3×7.3×5.4 cm. These lesions were significantly enlarged from an earlier CT scan completed two months prior to further evaluate for potential causes of hematochezia. Aspirations of both the pleural effusion and the splenic lesions failed to demonstrate infectious etiologies, but demonstrated numerous neutrophils.

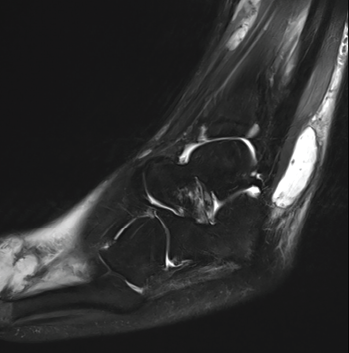

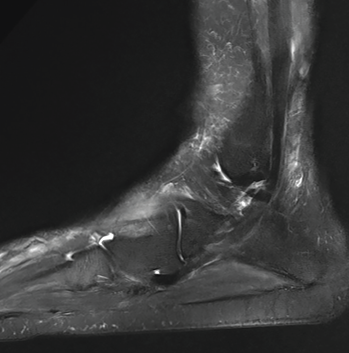

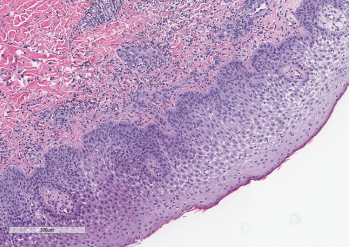

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of both feet demonstrated multiple, mildly complex, T2 hyperintense, loculated, intramuscular collections tracking along multiple tendons, with the largest one measuring 3.0×1.2×3.8 cm (see Figure 2A). It also showed a 1.0 cm calcaneal intraosseous collection concerning for an abscess. A punch biopsy of the bullous lesion on her right foot revealed mixed perivascular and interstitial inflammation with neutrophils in the epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissue (see Figure 3).

Figure 2A: This MRI of the patient’s left ankle (sagittal view) demonstrates a T2 hyperintense complex fluid collection within the posterolateral subcutaneous tissues overlying and coursing along the peroneus tendon and muscles. The collection measures 3.0×1.2×3.8 cm. This image also partly demonstrates a lobulated cystic-appearing fluid collection within the dorsal soft tissues of the forefoot.

Figure 2B: A later MRI demonstrates resolution of previously seen fluid collections after treatment with corticosteroids.

She was diagnosed with Sweet syndrome.

At this point, the patient had already completed several days of broad-spectrum antibiotics without resolution of fevers or improvement in symptoms. She received 50 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone for three days, with immediate signs of clinical improvement. She defervesced with a significant reduction in her CRP to 45.8 mg/L (RR: <8.1 mg/L). Her right hand pain and swelling, in addition to her skin lesions, rapidly improved with treatment. Her foot pain and swelling slowly improved, and she transitioned to oral prednisone.

Given the episode of hematochezia two months prior to admission, a gastroenterologist was consulted for a colonoscopy to identify an underlying cause of Sweet syndrome. A colonoscopy was performed and revealed perianal bullae and erythematous, granular and inflamed mucosa in the ascending colon and cecum.

Biopsies showed active colitis in the right colon, patchy active inflammation in the transverse colon and rectum, and crypt abscesses in the rectum. No granulomas were identified, and a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was made.

The patient was discharged home with a prolonged prednisone taper and plans to follow up with the gastroenterology and rheumatology services as an outpatient. Over the next two months, the patient began treatment with adalimumab for Crohn’s disease and completed her prednisone taper. A repeat MRI of her feet was performed three months after discharge and showed complete resolution of the abscesses (see Figure 2B).

Discussion

Sweet syndrome, or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a rare inflammatory disorder belonging to the family of neutrophilic dermatoses. The syndrome is characterized by fevers, sudden onset of painful erythematous plaques or nodules and dense neutrophilic infiltrates on biopsy. The three subtypes of Sweet syndrome are classic Sweet syndrome, malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome and drug-induced Sweet syndrome.

Figure 3: A punch biopsy demonstrated subepidermal edema overlying a dense neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis and epidermis. Courtesy Sandra Haddad, MD

Classic Sweet syndrome comprises most cases of Sweet syndrome and is often associated with infections, autoimmune diseases and inflammatory disorders.1 Diagnostic criteria for classic Sweet syndrome were initially presented by Su and Liu in 1986 and modified by von den Driesch in 1994.2,3 Diagnosis of classic Sweet syndrome is based on meeting both major criteria and two of the four minor criteria, as listed in Table 1. Our patient met both major criteria and all the minor criteria for a diagnosis of classic Sweet syndrome.

Table 1: Criteria for Diagnosis of Classic Sweet Syndrome

| Major Criteria | Minor Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Abrupt onset of tender or painful erythematous plaques or nodules, occasionally with vesicles, pustules or blisters 2. Evidence of dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology | 1. Fever >38ºC 2. Association with inflammatory disease or pregnancy or recent history of upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection 3. 3 out of 4 abnormal lab values at presentation a. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >20 mm/h b. Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) c. >8,000 leukocytes per μL d. >70% neutrophils 4. Response to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids |

Adapted from von den Driesch3

This case provides several learning points. The first point is the association of Sweet syndrome with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Classic Sweet syndrome has been reported as a rare extracutaneous manifestation in patients with IBD. Most of these cases have been reported in women and are associated with colonic disease.4,5 Further, it has been associated with active disease in up to 80% of patients.4,6

Patients who develop Sweet syndrome-associated IBD have more frequent extraintestinal manifestations of IBD, with one case report citing 77% of patients developing an extraintestinal manifestation.6 Sweet syndrome can present at any time in patients with IBD, with 21% of patients developing Sweet syndrome prior to a diagnosis of IBD.6

A second learning point is that any organ system can be involved in Sweet syndrome.7 One challenging aspect of this case was the numerous organ systems affected by Sweet syndrome. Our patient not only had skin and musculoskeletal involvement, but also demonstrated involvement of her lungs and splenic abscesses of impressive size. Given her daily high-grade fevers and abscesses seen in multiple organs on imaging, our gravest concern was an underlying infection. However, despite extensive treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics, her symptoms did not improve. Further, no organisms were identified despite sampling different fluid collections in multiple organs.

Our patient responded very well to corticosteroids, with complete resolution of multi-organ abscesses.

Arthritis, along with other musculoskeletal manifestations, have been reported in up to 59% of cases of Sweet syndrome.8 The arthritis is migratory, asymmetric, non‑deforming and involves at least two joints.8,9 The knees and wrists are reportedly the most frequently affected, followed by ankles, elbows and fingers.9 This arthritis improves with treatment of the underlying disorder.9

In Sum

We have described an unusual case of Sweet syndrome as the initial presentation of Crohn’s disease in a patient who presented with bullous skin lesions, splenic cysts, acute arthritis and an intraosseous calcaneal lesion. Sweet syndrome should be considered for patients presenting with joint pain in the setting of fevers and a new rash. Further, physicians should consider evaluating for possible autoimmune diseases to determine the underlying cause of Sweet syndrome.

In our case, the patient’s reported episode of hematochezia prompted a colonoscopy, which led to a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease as the underlying cause of Sweet syndrome, permitting the patient to receive appropriate treatment and recover in a timely manner.

Ryan Guerrettaz, MD, is an internal medicine-pediatrics resident, PGY-3, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Ryan Guerrettaz, MD, is an internal medicine-pediatrics resident, PGY-3, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Angelo Ciliberti, MD, is a rheumatology fellow, PGY-5, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Angelo Ciliberti, MD, is a rheumatology fellow, PGY-5, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Rochella A. Ostrowski, MD, MS, is an associate professor and rheumatology fellowship program director, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill., and Edward Hines Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital, Hines, Ill.

Rochella A. Ostrowski, MD, MS, is an associate professor and rheumatology fellowship program director, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill., and Edward Hines Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital, Hines, Ill.

Elise Wolff, DO, is a clinical instructor at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Elise Wolff, DO, is a clinical instructor at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Nadia K Qureshi, MD, is associate professor of pediatrics at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Nadia K Qureshi, MD, is associate professor of pediatrics at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Ramzan Shahid, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Ramzan Shahid, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sandra Haddad, MD, of the pathology service of Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill., for the contribution of Figure 3.

References

- Heath MS, Ortega-Loayza AG. Insights into the pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019 Mar 12;10:414.

- Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986 Mar; 37(3):167–174.

- von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994 Oct;31(4):535–556.

- Díaz-Peromingo JA, García-Suárez F, Sánchez-Leira J, Saborido-Froján J. Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with acute ulcerative colitis: Presentation of a case and review of the literature. Yale J Biol Med. May–Jun 2001;74(3):165–168.

- Ali M, Duerksen DR. Ulcerative colitis and Sweet’s syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008 Mar;22(3):296–298.

- Travis S, Innes N, Davies MG, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: An unusual cutaneous feature of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. The South West Gastroenterology Group. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997 Jul;9(7):715–720.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: A review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003 Oct;42(10):761–778.

- Nolla JM, Juanola X, Valverde J, et al. Arthritis in acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome). Ann Rheum Dis. 1990 Feb;49(2):135.

- Moreland LW, Brick JE, Kovach RE, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome): A review of the literature with emphasis on musculoskeletal manifestations. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1988 Feb;17(3):143–153.