A 65-year-old woman was referred by an orthopedist to a rheumatologist for left knee pain. Previously, in 2014, she underwent left total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for severe osteoarthritis in a different institution. Following the procedure, she experienced severe chronic anterolateral knee pain at rest, exacerbated by walking. Because she was rendered wheelchair bound and required chronic narcotic analgesia, she sought a second orthopedic opinion at our institution in 2015.

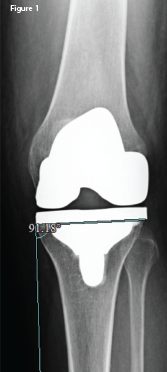

An anteroposterior X-ray of the left knee following the original arthroplasty. It shows a lateral femoral and tibial overhang of

4–5 mm and 3 mm, respectively.

An orthopedic exam revealed decreased and painful range of motion of the knee, but no lower extremity neurologic deficits. X-rays revealed significant femoral and tibial lateral overhang (see Figure 1, right) of the components. After a thorough evaluation for underlying infection, which included aspiration, bone scan and acute phase reactants, a partial revision of the left knee implant was undertaken.

The original size 4 femoral component was replaced with a size 3 component, eliminating the lateral femoral component overhang, which was found to be 4–5 mm at surgery. Following surgery, the patient’s pain improved to the point that she could walk with a cane. However, despite physical therapy, topical agents and oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), significant pain persisted, warranting further investigation.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine did not reveal a radicular source of knee pain. Lower extremity venous duplex revealed no deep venous thrombosis. A trial of radiofrequency ablation of the left genicular nerves afforded only transient relief. Narcotics were still necessary, but became less effective.

The patient was then referred to a rheumatologist for evaluation of occult causes of knee pain and a sonographic evaluation to look for structural problems, such as a neuroma.

During the rheumatologic evaluation, the patient described constant, intense burning pain localized to the left lateral knee and markedly affecting activities of daily living (ADLs). Bending her knee and walking continued to intensify her pain. She denied radiation of the pain and lower extremity paresthesias.

The physical exam revealed diminished flexion of the left knee to 85º. The knee was sensitive to palpation over the anterolateral surface. Tinel’s sign over the common peroneal nerve (CPN) was negative. No evidence of left foot drop or foot dorsiflexion weakness was apparent.

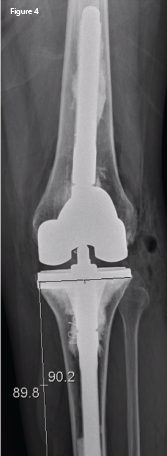

The patient’s laboratory workup was entirely negative or normal including acute phase reactants, rheumatoid factor, complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel. X-ray revealed a 3 mm lateral overhang of the tibial component.

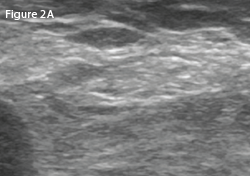

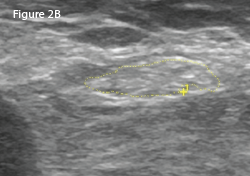

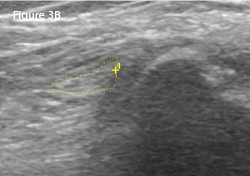

Ultrasound of the left knee revealed a single, deep inferior, lateral, genicular neuroma with only mild tenderness to sonopalpation. In contrast, the left CPN was markedly tender to sonopalpation. Cross-sectional areas (CSA) of the left (affected) and right (unaffected) CPNs were measured and noted to be 21 mm2 and 8 mm2, respectively (see Figure 2, below & Figure 3) Ultrasound did not demonstrate the left CPN to be hypoechoic or displaced by the protruding tibial component of the knee prosthesis.

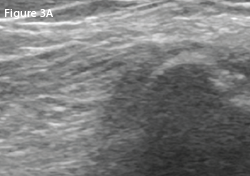

Left: A transverse view of the posterolateral left (affected) knee at the level of the fibula.

Right: The same view as 2A, with the common peroneal nerve outlined in yellow with a cross-sectional area of 21 mm2.

LEFT: A transverse view of the posterolateral right (unaffected) knee at the level of fibula.

RIGHT: The same view as 3A, with the common peroneal nerve outlined in yellow with a cross-sectional area of 8 mm2.

Subsequent electrophysiologic studies (EPS) revealed the left superficial peroneal nerve sensory portion to be unresponsive, suggestive of peroneal nerve compression. Motor function of the nerve was intact.

It was concluded the mildly tender neuroma was not clinically significant in comparison with the ultrasonic findings of the left CPN, supported by the abnormal EPS.

CPN neuropathy has been described as a rare occurrence following total & unicompartmental knee arthroplasty.

An anteroposterior X-ray of the left knee following revision arthroplasty. The lateral femoral and tibial overhang has been eliminated.

The patient agreed to a second TKA revision for progressive varus deformity. A smaller prosthesis was used, with the intention of decompressing the common peroneal nerve and eliminating the varus deformity. Figure 4) demonstrates the TKA revision with correction of both the tibial and femoral lateral overhang.

Seven months post-operative, the patient reported her pain—and ADLs—to be markedly improved.

Discussion

Etiology of Peroneal Neuropathy at the Knee

The sciatic nerve arises from the lumbosacral ventral rami and divides into the common peroneal and tibial nerves just proximal to the popliteal fossa. The CPN, which receives contributions from L4–5 and S1–2, courses lateral to the biceps femoris tendon and fibula head, a location vulnerable to injury.

Common peroneal nerve palsy may occur with tibia and fibula fracture, knee dislocation, sports injuries, iatrogenic surgical trauma, compression from a ganglion cyst, osteochondroma, aneurysm and various mass lesions.1-8 Excessive weight loss may predispose a patient to CPN neuropathy as well.9-11 Although the precise incidence is unknown, CPN neuropathy has been described as a rare occurrence following total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty.1,7,8,12 The mechanism of CPN neuropathy after TKA is unclear, but may be due to soft tissue compression or traction on the nerve.8

Clinical Presentation of Peroneal Neuropathy after TKA

Peroneal neuropathy after knee arthroplasty may manifest as weakness, persistent radiating pain, loss of sensation and paresthesias—all symptoms that interfere with rehabilitation and ADLs.1,7,8,12 Of interest is that CPN neuropathy after TKA may exhibit nonspecific symptoms, including localized pain and decreased range of motion, which may also hinder full functional recovery.1 This has been described as CPN dysfunction, but may still be definitively diagnosed by EPS.1

Traditional Evaluation of Suspected Peroneal Nerve Injury

MRI of the knee may define underlying pathology involving the CPN, with EPS confirming the diagnosis.2 MRI of the knee after arthroplasty may be challenging due to distortions generated by metallic artifact production, even when optimized pulse sequences are used.13

Regarding nerve damage, EPS defines abnormal function and injury location but not the underlying pathology.14

Ultrasound & the Common Peroneal Nerve at the Knee

In response to chronic compression, peripheral nerves may enlarge and/or change echotexture.15 More recently, ultrasound findings, corroborated by EPS, have been helpful in evaluating CPN neuropathy by directly visualizing the nerve and structures that may cause nerve compression.14,16-18 The most consistently reported ultrasound-measured abnormality in CPN compressive neuropathy is enlargement of the CSA of the affected CPN. In several studies, ultrasound-measured enlargement of the CSA of the CPN correlated well with abnormal EPS.14,16-18 In the largest of the studies, 87 patients with CPN neuropathy based on clinical examination and abnormal EPS were evaluated by ultrasound. Using a CPN cutoff of a CSA of 10.9 mm2, ultrasound diagnostic sensitivity was 90%, with specificity of 69%.16

However, none of the studies looked at CPN neuropathy following knee arthroplasty.

Treatment Options for Common Peroneal Neuropathy after TKA

For compressive CPN neuropathy following TKA and lasting three months or more, nonsurgical treatment (e.g., medication, splinting and physical therapy) has yielded variable results.1,19,20 Surgical decompression of the common peroneal nerve after TKA has more consistently produced successful results, although large studies are lacking.1,19,20

Is Knee Arthroplasty Component Overhang Important?

The relation of tibial and femoral component overhang to pain and outcome after TKA is a topic of interest beyond the scope of this discussion.21-23 However, in our single case, correction of the femoral component overhang alone was insufficient for a good outcome. Our patient achieved marked pain relief when both the lateral tibial and femoral component overhang and the varus deformity were corrected.

Conclusion

The clinical presentation of CPN neuropathy after TKA may present atypically, with only pain and/or decreased knee range of motion.1 This presentation without nerve palsy or paresthesias is termed CPN dysfunction and may be considered a subset of CPN neuropathy.1 Ultrasound examination of the CPN, quantitating CSA and comparing it with the unaffected nerve may be useful to evaluate for CPN compressive neuropathy in cases of TKA with suboptimal results. Confirmation with EPS is still necessary.

Regarding compressive neuropathies, ultrasound and EPS are complementary; the former assesses morphology, and the latter measures physiologic nerve function.18 Surgical decompression appears to be the most successful treatment option for CPN compressive neuropathy with either classic neuropathy or dysfunction.19,20

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported use of ultrasound as the initial screening modality for CPN dysfunction after TKA.

Mark H. Greenberg, MD, RMSK, RhMSUS, is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine at Palmetto Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C.

Elijah Mitcham, MD, graduated from Mercer University School of Medicine, Georgia, and completed his internal medicine residency at Palmetto Health/University of South Carolina.

Prem Patel is a medical student at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Columbia. He graduated from the University of South Carolina with a BS in biomedical engineering.

James W. Fant Jr., MD, is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and director of the Rheumatology Division at Palmetto Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C.

Frank R. Voss, MD, is an associate professor of orthopedic surgery, director of medical education for orthopedic surgery and the department’s vice chair at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine. He is board certified in orthopedic surgery.

References

- Zywiel MG, Mont MA, McGrath MS, et al. Peroneal nerve dysfunction after total knee arthroplasty: Characterization and treatment. J Arthroplasty. 2011 Apr;26(3):379–385.

- Baima J, Krivickas L. Evaluation and treatment of peroneal neuropathy. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008 Jun;1(2):147–153.

- Clark NE, Bobo LS, Ho CA. Knee dislocation with common peroneal nerve rupture. International Journal of Athletic Therapy and Training. 2013;18(5):29–31.

- Coraci D, Tsukamoto H, Granata G, et al. Fibular nerve damage in knee dislocation: Spectrum of ultrasound patterns. Muscle Nerve. 2015 Jun;51(6):859–863.

- Dan C, Ispas AT, Vasilescu M, et al. Sport related injuries of the nerves in the knee region. Medicina Sportiva. 2014;

10(3):2364–2368.

- Kim JY, Ihn YK, Kim JS, et al. Non-traumatic peroneal nerve palsy: MRI findings. Clinical Radiology. 2007 Jan;62(1):58–64.

- Idusuyi OB, Morrey BF. Peroneal nerve palsy after total knee arthroplasty: Assessment of predisposing and prognostic factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996 Feb;78(2):177–184.

- Rose HA, Hood RW, Otis JC, et al. Peroneal-nerve palsy following total knee arthroplasty. A review of The Hospital for Special Surgery experience. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982 Mar;64(3):347–351.

- Margulis M, Ben Zvi L, Bernfeld B. Bilateral common peroneal nerve entrapment after excessive weight loss: Case report and review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2018 May–Jun;57(3):632–634.

- Sotaniemi KA. Slimmer’s paralysis—peroneal neuropathy during weight reduction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984 May;47(5):564–566.

- Elias, WJ, Pouratian N, Oskouian RJ, et al. Peroneal neuropathy following successful bariatric surgery. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2006 Oct;105(4):631–635.

- Agarwal M, Syed AA, Singh R, Kamdar BA. Common peroneal nerve palsy after lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003 Jan;18(1):92–95.

- Fritz J, Lurie B, Potter HG. MR imaging of knee arthroplasty implants. Radiographics. 2015 Sep–Oct;35(5):1483–1501.

- Bayrak İK, Oytun Bayrak A, Turker H, et al. Diagnostic value of ultrasonography in peroneal neuropathy. Turk J Med Sci. 2018 Dec;48(6):1115–1120.

- Suk JI, Walker FO, Cartwright MS. Ultrasound of peripheral nerves. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013 Feb;13(2):328.

- Visser LH, Hens V, Soethout M, et al. Diagnostic value of high-resolution sonography in common fibular neuropathy at the fibular head. Muscle Nerve. 2013 Aug;48(2):171–178.

- Kim JY, Song S, Park HJ, et al. Diagnostic cutoff value for ultrasonography of the common fibular neuropathy at the fibular head. Ann Rehabil Med. 2016 Dec;40(6):1057–1063.

- Nageeb RS, Mohamed WS, Nageeb GS, et al. Role of superficial peroneal sensory potential and high-resolution ultrasonography in confirmation of common peroneal mononeuropathy at the fibular neck. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatr Neurosurg. 2019 Mar 28;55(23).

- Krackow KA, Maar DC, Mont MA, et al. Surgical decompression for peroneal nerve palsy after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993 Jul;292:223–228.

- Ward JP. Yang LJ-S, Urquhart AG. Surgical decompression improves symptoms of late peroneal nerve dysfunction after total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2013 Apr;36(4):e515–e519.

- Mahoney OM, Kinsey T. Overhang of the femoral component in total knee arthroplasty: Risk factors and clinical consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010 May;92(5):1115–1121.

- Chau R, Gulati A, Pandit H, et al. Tibial component overhang following unicompartmental knee replacement—Does it matter? Knee. 2009 Oct;16(5):310–313.

- Abram SG, Marsh AG, Brydone AS, et al. The effect of tibial component sizing on patient reported outcome measures following uncemented total knee replacement. Knee. 2014 Oct;21(5):955–959.