Figure 1. Reticulated violaceous rash of the bilateral lower extremities found on initial presentation.

Approximately six months prior to developing the rash, she was clinically diagnosed with temporal arteritis based on temporal headaches, jaw claudication, scalp tenderness and an excellent response to prednisone. The patient had no history of renal disease, hypothyroidism, liver disease or malignant neoplasm, and no known personal or family history of bleeding or clotting disorders. In addition to warfarin and prednisone, the patient’s medication list at the time of her initial visit also included atorvastatin, quinapril, metoprolol and vitamin D.

On examination, patches of retiform purpura and scattered small (less than 1 cm), necrotic papules on the patient’s lateral calves and medial shins were noted bilaterally. Even though she was taking prednisone, a medium vessel vasculitis with possible occlusive vasculitis was suspected by gross examination on the basis of retiform purpura and the small necrotic ulcerations that had started to develop (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Development of retiform purpura and the small necrotic ulcerations.

Laboratory evaluation yielded negative anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, extractable nuclear antigens, rheumatoid factor (<4 IU/mL, normal 0–15 IU/mL), cyclic citrullinated peptic antibody (<0.40 U/mL, normal 0.00–4.99) and serum protein electrophoresis. C3 and C4 complements were both within the normal range, 172.4 mg/dL (normal 90.0–180.0 mg/dL) and 39.1 mg/dL (normal 10.0–40.0 mg/dL), respectively. C-reactive protein was mildly elevated at 3.30 mg/dL (normal 0.00–0.90 mg/dL) and sedimentation rate was within normal range at 10 mm/hr (normal 0–20 mm/hr).

Several skin biopsies were performed, which included an incisional biopsy, a tissue culture biopsy, as well as a biopsy for direct immunofluorescence. Despite these efforts, no definitive histopathological diagnosis, such as vasculitis, calciphylaxis or thrombotic vasculopathy, resulted. In addition, direct immunofluorescence, tissue bacterial cultures and acid-fast cultures were negative. With continued worsening of the patient’s clinical presentation, a drug-induced phenomenon was considered.

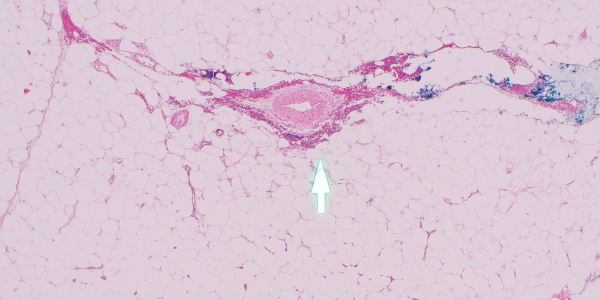

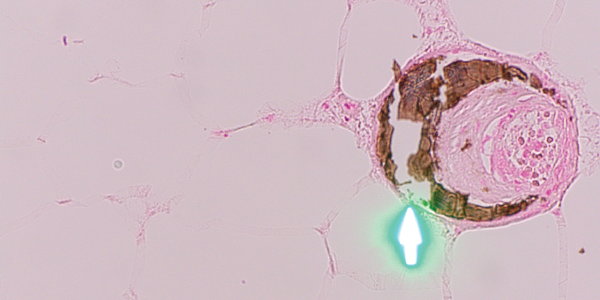

Fortunately, the patient was only on a few medications, so warfarin was considered the most likely culprit and was therefore discontinued. Apixaban replaced warfarin for her atrial fibrillation. She was then referred to a tertiary care center for a second opinion. A third set of biopsies finally revealed subcutaneous fibrin thrombi involving the microvasculature, intimal wall thickening and stippled, partially occlusive, calcification consistent with calciphylaxis (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figures 3

Figure 4. H&E and Von Kossa stain, respectively. The third set of biopsies revealed subcutaneous fibrin thrombi involving the microvasculature, intimal wall thickening and stippled, partially occlusive calcification consistent with calciphylaxis.

After the diagnosis was made, the patient was started on intravenous infusions of sodium thiosulfate, given the success of this regimen for calcific uremic arteriolopathy.7 The patient returned two months later to the dermatology and rheumatology clinics with significant improvement and minimal resultant scarring from previous necrotic tissue development (see Figure 5, right). Interestingly, the patient reported that improvement seemed to begin soon after discontinuation of the warfarin and prior to beginning sodium thiosulfate.