Calciphylaxis, or calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare disease characterized by calcification of the arterioles and capillaries in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, resulting in thrombus formation and subsequent skin ischemia and necrosis.1 This serious condition most commonly occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring dialysis or in kidney transplant recipients. In rare cases, warfarin has been associated with non-ESRD-related calciphylaxis.1

Diagnosis of this disease can be challenging because it can mimic a vasculitis.2 We describe a patient without ESRD but on warfarin who presented with necrotizing skin lesions of unknown etiology and was eventually diagnosed with calciphylaxis. This case proved challenging due to the atypical etiology of this rare disease, its presentation clinically as a vasculitis and the requirement of multiple biopsies for a definitive diagnosis.

Introduction

Calciphylaxis is classically a disease associated with renal failure, with the majority of patients nearing or on dialysis.2 This condition can also occur without kidney disease, termed non-uremic calciphylaxis, and is most commonly associated with derangements in calcium and phosphate homeostasis, such as hyperphosphatemia, hypercalcemia and thyroid disease.2 Additionally, cases of exposure to warfarin as a cause for calciphylaxis have been documented.1 Non-uremic calciphylaxis is thought to be a small subset of overall calciphylaxis cases. As of 2016, 116 cases had been identified.3 Warfarin-induced non-uremic calciphylaxis represents an even smaller subset of these cases.

The suspected mechanism by which warfarin induces calciphylaxis is through the inhibition of vitamin K-dependent carboxylation of matrix Gla-protein, a mineral-binding extracellular matrix protein that prevents calcium deposition in arteries.4 This leads to progressive narrowing of cutaneous blood vessel lumens through calcification within the media layer of vessel walls and by the proliferation of endothelial cells and fibrosis underneath the intima.2 Thrombosis is the final step in calciphylaxis, which ultimately leads to complete vessel occlusion. Warfarin decreases protein C levels faster than the coagulation factors, therefore increasing thrombus formation.5 Ultimately, with microvascular thrombosis, ischemia develops.

Calciphylaxis often presents as cutaneous lesions of livedo reticularis, plaques, nodules and ulcers due to ischemia of the microvasculature.2 Plaques or nodules are the most common presenting lesions, which may be confused with cellulitis because both lesions can present with erythema, pallor and tenderness.2 Patients may have advanced disease, however, once the diagnosis is officially made.

Case Report

A 77-year-old woman with a past medical history of atrial fibrillation on 5 mg of warfarin daily for over a year and non-biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis on 25 mg of prednisone once a day presented to the dermatology and rheumatology clinics with a four-month history of a worsening reticulated violaceous rash on both her legs (see Figure 1). The rash initially started as a “black scab” on her left mid-shin. However, over the course of a month or so, she developed progressive, escalating pain as the areas of involvement increased in size and severity and, eventually, involved both shins.

Figure 1. Reticulated violaceous rash of the bilateral lower extremities found on initial presentation.

Approximately six months prior to developing the rash, she was clinically diagnosed with temporal arteritis based on temporal headaches, jaw claudication, scalp tenderness and an excellent response to prednisone. The patient had no history of renal disease, hypothyroidism, liver disease or malignant neoplasm, and no known personal or family history of bleeding or clotting disorders. In addition to warfarin and prednisone, the patient’s medication list at the time of her initial visit also included atorvastatin, quinapril, metoprolol and vitamin D.

On examination, patches of retiform purpura and scattered small (less than 1 cm), necrotic papules on the patient’s lateral calves and medial shins were noted bilaterally. Even though she was taking prednisone, a medium vessel vasculitis with possible occlusive vasculitis was suspected by gross examination on the basis of retiform purpura and the small necrotic ulcerations that had started to develop (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Development of retiform purpura and the small necrotic ulcerations.

Laboratory evaluation yielded negative anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, extractable nuclear antigens, rheumatoid factor (<4 IU/mL, normal 0–15 IU/mL), cyclic citrullinated peptic antibody (<0.40 U/mL, normal 0.00–4.99) and serum protein electrophoresis. C3 and C4 complements were both within the normal range, 172.4 mg/dL (normal 90.0–180.0 mg/dL) and 39.1 mg/dL (normal 10.0–40.0 mg/dL), respectively. C-reactive protein was mildly elevated at 3.30 mg/dL (normal 0.00–0.90 mg/dL) and sedimentation rate was within normal range at 10 mm/hr (normal 0–20 mm/hr).

Several skin biopsies were performed, which included an incisional biopsy, a tissue culture biopsy, as well as a biopsy for direct immunofluorescence. Despite these efforts, no definitive histopathological diagnosis, such as vasculitis, calciphylaxis or thrombotic vasculopathy, resulted. In addition, direct immunofluorescence, tissue bacterial cultures and acid-fast cultures were negative. With continued worsening of the patient’s clinical presentation, a drug-induced phenomenon was considered.

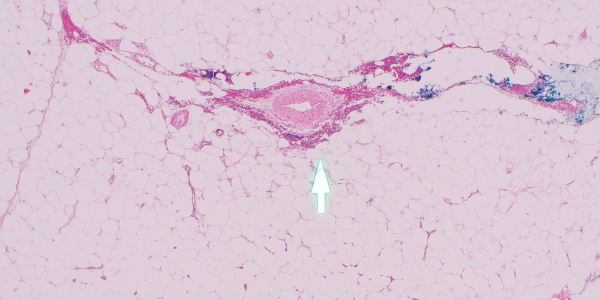

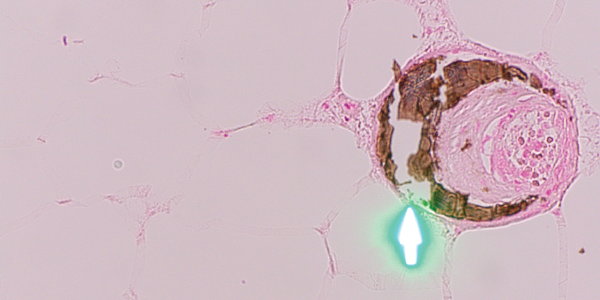

Fortunately, the patient was only on a few medications, so warfarin was considered the most likely culprit and was therefore discontinued. Apixaban replaced warfarin for her atrial fibrillation. She was then referred to a tertiary care center for a second opinion. A third set of biopsies finally revealed subcutaneous fibrin thrombi involving the microvasculature, intimal wall thickening and stippled, partially occlusive, calcification consistent with calciphylaxis (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figures 3

Figure 4. H&E and Von Kossa stain, respectively. The third set of biopsies revealed subcutaneous fibrin thrombi involving the microvasculature, intimal wall thickening and stippled, partially occlusive calcification consistent with calciphylaxis.

After the diagnosis was made, the patient was started on intravenous infusions of sodium thiosulfate, given the success of this regimen for calcific uremic arteriolopathy.7 The patient returned two months later to the dermatology and rheumatology clinics with significant improvement and minimal resultant scarring from previous necrotic tissue development (see Figure 5, right). Interestingly, the patient reported that improvement seemed to begin soon after discontinuation of the warfarin and prior to beginning sodium thiosulfate.

Discussion

Due to the nondescript nature of calciphylaxis in the early stages, patients are often diagnosed with advanced disease.2 In our case, diagnosis of calciphylaxis was not officially made until the third sets of biopsies. This may have been due to the early stage of disease at the time of the first two biopsies. Yu et al. found in their study of patients with non-uremic calciphylaxis that roughly half of the patients known to have had warfarin-induced calciphylaxis required multiple biopsies to obtain a definitive diagnosis.5 This demonstrates that obtaining a definitive diagnosis through biopsies can be challenging and require multiple biopsy attempts.

In our case, the patient lacked other etiologies for the skin lesions. Therefore, calciphylaxis was high on our differential, despite initially negative biopsies. Fortunately, the patient was not on many medications, so warfarin was suspected as the most likely culprit. Warfarin was discontinued in favor of an alternative anticoagulant.

Once warfarin was discontinued, the patient showed slow improvement and eventual resolution of her skin lesions. It is likely, therefore, that the cause of the patient’s calciphylaxis was, indeed, the warfarin.

It’s unclear whether warfarin-induced calciphylaxis is clinically different from classic calciphylaxis. Yu et al. assert warfarin-

induced calciphylaxis is distinct in pathogenesis, course of disease and outcome. The authors noted that of the 18 patients studied, the location of the rash was below the knee in 12 of the 18 patients, and 15 of the 18 cases achieved full recovery.5 This is markedly different from the overall prognosis for calciphylaxis, in general, which is reported to have over a 50% one-year mortality rate.6 Similar to cases in this study, our patient presented with lesions on both lower extremities below the knee and achieved a full recovery with some minor residual scarring (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Healing lesions on both legs.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of keeping warfarin-induced calciphylaxis on the differential when a patient presents with signs and symptoms of a medium vessel vasculitis and concurrent warfarin use. Moreover, this case also demonstrates that clinicians should include calciphylaxis in the differential even if initial biopsies fail to initially demonstrate characteristic features.

Marie V. Dardeno, DO, is third-year resident in the Maine-Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency Program, Augusta.

Marie V. Dardeno, DO, is third-year resident in the Maine-Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency Program, Augusta.

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, precepts family practice residents in the Maine-Dartmouth Family Residency Program, Augusta, and sees a full panel of dermatology patients in central Maine. He served as an Army dermatologist for 13 years.

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, precepts family practice residents in the Maine-Dartmouth Family Residency Program, Augusta, and sees a full panel of dermatology patients in central Maine. He served as an Army dermatologist for 13 years.

William Monaco, MD, is a rheumatologist practicing in Augusta, Maine. He completed his internal medicine residency and rheumatology fellowship at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H.

William Monaco, MD, is a rheumatologist practicing in Augusta, Maine. He completed his internal medicine residency and rheumatology fellowship at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H.

References

- Nigwekar SU. Calciphylaxis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017 Jul;26(4):276–281.

- Chang JJ. Calciphylaxis: Diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019 May;32(5):205–215.

- Schurgers LJ, Cranenburg ECM, Vermeer C. Matrix Gla-protein: The calcification inhibitor in need of vitamin K. Thromb Haemost. 2008 Oct;100(4):593–603.

- Bajaj R, Courbebaisse M, Kroshinsky D, et al. Calciphylaxis in patients with normal renal function: A case series and systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018 Sep;93(9):1202–1212.

- Yu WY, Bhutani T, Kornik R, et al. Warfarin-associated nonuremic calciphylaxis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Mar 1;153(3):309–314.

- Weenig RH. Pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: Hans Selye to nuclear factor kappa-B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Mar;58(3):458–471.

- Nigwekar SU, Brunelli SM, Meade D, et al. Sodium thiosulfate therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 Jul 3; 8(7): 1162–1170.