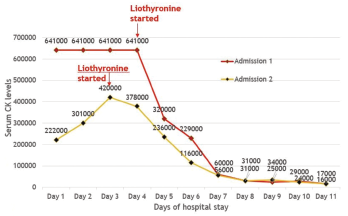

Figure 1: CK Trends During Hospitalization

Rhabdomyolysis is a clinical syndrome characterized by muscle tissue necrosis and release of intramuscular components into the circulation. Typical manifestations include muscle pain and myoglobinuria, causing dark urine. Serum creatinine kinase (CK) enzyme levels are usually markedly elevated. Severity can range from muscle enzyme elevation in the serum of an otherwise asymptomatic patient to extremely high enzyme elevations, causing acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalance and life-threatening disease with kidney or other organ failure.

We present a case of severe rhabdomyolysis from an unusual cause and associated with much greater CK levels than have been previously reported.

The Case

A 24-year-old African American man came to the hospital with dizziness, dark-colored urine and decreased urine output of four days’ duration. He described increased thirst and had experienced an episode of non-bloody vomiting three days before. He had experienced a few episodes of non-bloody diarrhea six days prior to admission. He smoked marijuana three days prior to symptom onset. He described generalized muscle aches and progressive fatigue. He had no fevers or chills, respiratory symptoms or joint symptoms. Prior to this episode, he’d had no history of exertion or trauma. He was not taking any new medications or using protein supplements. He had never taken a statin.

He had a prior history of congenital panhypopituitarism, diagnosed when he was 2 years old; since that time, he had taken levothyroxine, prednisone and testosterone supplements.

A physical examination revealed tachycardia of 120 beats per minute, but he was otherwise hemodynamically stable. He had normal muscle bulk and tone, and minimal generalized muscle tenderness; his muscle power was 5/5 in all four extremities, as well as in the neck muscles. He had no thyromegaly and no synovitis or rashes.

His laboratory results showed an elevated serum creatinine level of 2.4 mg/dL, and elevated aspartate and alanine transaminase levels of 1,144 and 232 U/L respectively. His CK level was remarkably elevated at 641,820 U/L, and his lactate dehydrogenase level was 10,817 U/L. The markedly elevated CK level was confirmed with repeat analysis, as well as analysis at a different laboratory (see Figure 1).

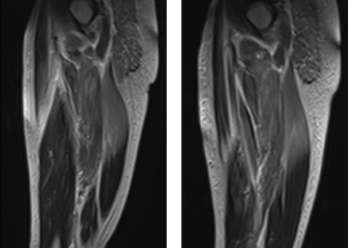

Figure 2: MRI. Magnetic resonance imaging of the bilateral thigh musculature shows extensive increased T2 signal throughout the gluteal musculature, as well as thigh musculature, most prominently in the posterior compartment.

His aldolase level was normal. His inflammatory markers were only minimally elevated, his erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 19 mm/h, and he had a C-reactive protein level of 11.2 mg/dL. His thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level was low, at 0.06 mU/L, which was thought to be due to underlying secondary hypothyroidism from panhypopituitarism. His free T4 level was at the lower limit of normal.

Urinalysis showed significant myoglobinuria. Testing for common viral infections causing muscle involvement was negative. His serologies, including anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), extractable nuclear antigen panel (ENA), myositis-specific and associated antibodies were all negative.

He had experienced a similar constellation of symptoms a year prior, at which time he had severe rhabdomyolysis with a CK level of 82,000 IU/L, which resolved with intravenous (IV) hydration alone and was thought to have an undiagnosed viral etiology.

He reported that his mother also had hypothyroidism and mild systolic heart failure with an ejection fraction of 40%.

The differential diagnosis at this point included:

- Rhabdomyolysis secondary to a viral infection;

- A toxin- or drug-induced myopathy;

- A metabolic myopathy; or

- An idiopathic inflammatory myopathy.

Aggressive intravenous hydration was initiated; however, his serum CK remained elevated. He developed oliguric acute renal failure secondary to pigment-induced, acute, tubular necrosis, which required hemodialysis. He also developed hypoxia due to heart failure from non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 15–25%; this was followed by an episode of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia that required use of a personal defibrillator device.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the thigh musculature showed extensively increased T2 signal throughout the gluteal and thigh muscles, which was interpreted as possibly consistent with an inflammatory myopathy (see Figure 2).

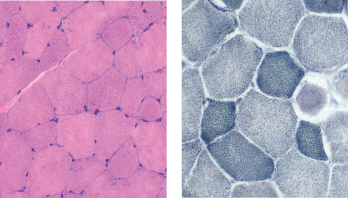

In the next evaluation step, a skeletal muscle biopsy was performed (see Figure 3). It revealed mildly increased variation in single fiber sizes, with few ring fibers. No inflammation was seen. (Note: These findings are non-specific and can be seen in muscular dystrophies, chronic myopathies or during myofiber regeneration). Electromyography showed non-specific myopathic changes. His urine toxicology screen was positive for cannabinoids, but otherwise unremarkable.

At this point, highest on the differential diagnosis was an undiagnosed myotonic dystrophy, possibly precipitated by stress from a viral illness, especially given that his mother also had cardiac muscle dysfunction. However, genetic testing for myotonic dystrophy was unrevealing. Additionally, genetic testing of both parents did not identify any abnormalities associated with myotonic dystrophy. Electron microscopy of the skeletal muscle biopsy was inconclusive. Tests for metabolic myopathies were also unremarkable.

Figure 3: Muscle Biopsy. Hemotoxylin and eosin staining (left) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide staining (right) show mildly increased variation in single fiber sizes, with ring fibers.

Thyroid studies demonstrated a total T3 of 13 ng/dL (normal 70–204 ng/dL) and a low free T3 level of 1.1 pg/mL (normal 1.5-4.1 pg/mL). He was thought to have severe secondary hypothyroidism from inadequate, decreased peripheral conversion of T4 to T3 due to inadequate T4 supplementation, causing hypothyroid myopathy and precipitating rhabdomyolysis and cardiac muscle dysfunction.

He was started on T3 hormone supplementation with liothyronine (Cytomel). The next day, his serum CK level started improving, and within a week, his CK level decreased from 641,000 U/L to 17,000 U/L. The patient improved clinically as well, with resolution of his myalgias, dark urine and fatigue.

In a month, his renal function returned to normal, and he was able to stop hemodialysis. His cardiac function recovered, and a repeat echocardiogram demonstrated a systolic ejection fraction of 40–50%. The patient was able to resume his routine life and work. Repeat outpatient CK testing demonstrated a normal CK (81 U/L).

About a year later, he had another episode of rhabdomyolysis with a serum CK of 420,000 U/L, in the setting of non-adherence with liothyronine supplementation. He was restarted on liothyronine supplementation, again with resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Serum CK is frequently elevated in patients with hypothyroidism (57–80% cases) and in most of these cases, the associated muscle disease is mild or asymptomatic.1,2 CK levels are elevated in hypothyroidism due to direct muscle cell damage, downregulation of cellular metabolism and a reversible defect in glycogenolysis.3 However, several cases of severely high CK levels and rhabdomyolysis have been reported in the literature. Of all these cases, the mean CK level was around 16,000 U/L and the maximum CK levels reported have been around 32,000 U/L.4-7

This case is unique because the patient had hypothyroid myopathy due to low T3 from decreased peripheral conversion of T4 to T3 and inadequate T4 supplementation, in addition to underlying panhypopituitarism causing a deceptively low TSH level. Additionally, CK levels of 641,000 U/L secondary to hypothyroid myopathy leading to rhabdomyolysis has not been previously reported in medical literature, to the best of our knowledge.

This patient’s hypothyroidism is due to congenital hypopituitarism. Because of this, his TSH will not respond to T4 supplementation. On lab investigations, his T4 level was adequate, but his T3 level was not. This could have been due to lack of availability of sufficient T4 to convert to T3 peripherally.

In a typical patient, this is easy to diagnose by checking the response in TSH level to determine whether the T4 supplementation dose is adequate or not. However, this is not possible when the TSH is low because of pituitary deficiency. Theoretically, it would have been possible to give our patient larger doses of T4 supplementation to see if his T3 level improved, but it is much easier and faster to give T3 supplementation directly and assess for clinical response.

Hypothyroidism is an uncommon cause of severe rhabdomyolysis. Risk factors for precipitating rhabdomyolysis in patients with hypothyroid myopathy are vigorous exercise, coexisting hepatic or renal insufficiency and concomitant statin use.8-10 Worsening acute kidney injury or acute renal failure may occur as a secondary complication.

The diagnosis of hypothyroid myopathy is based on a thorough history and physical exam to assess for other clinical features of hypothyroidism, as well as on complete serum thyroid function testing. Clinical features of hypothyroid myopathy may include myalgias, stiffness, pseudohypertrophy (or cramps), proximal myopathy with weakness, fatigue, slowed movements and reflexes, myxedema, dry skin, hoarseness, exertional dyspnea, asymptomatic pleural or pericardial effusions, cardiomegaly and associated carpal tunnel syndrome.2,11

The degree of CK elevation may correlate with the severity of hypothyroidism in some but not all cases. Both electromyography and muscle biopsy findings are usually non-specific. Electromyography findings are extremely variable and can reveal abnormal, spontaneous muscle activity or, rarely, typical myopathic patterns.2,12 Muscle biopsy is usually normal or demonstrates non-specific abnormalities. Sometimes, variability in fiber size and selective atrophy of type II fibers with myofibrillar ATPase activity shift to slow fibers (type I) can occur. Sometimes, such findings as type I fiber hypertrophy, degenerating fibers, internalized nuclei and core-like structures, an increase in mitochondria distributed in perinuclear and sarcolemmal regions, and increased intracellular glycogen and lipid concentrations may occur.2,13

Treatment with thyroid hormone supplementation (T4 and/or T3 supplementation) usually leads to rapid resolution of the myopathy and rhabdomyolysis.2 Our patient will need to stay on T3 supplementation to prevent further episodes of rhabdomyolysis.

Aditya S. Pawaskar, MBBS, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington. Dr. Pawaskar earned his medical degree from Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College, Mumbai, India. He completed residency training in internal medicine at Westchester Medical Center of New York Medical College.

Aditya S. Pawaskar, MBBS, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington. Dr. Pawaskar earned his medical degree from Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College, Mumbai, India. He completed residency training in internal medicine at Westchester Medical Center of New York Medical College.

Weishali V. Joshi, MD, is the section chief of rheumatology at Trinity Health of New England Medical Group, Saint Francis Hospital and Medical Center, Hartford, Conn. Dr. Joshi earned her medical degree from Grant Medical College, Mumbai. She completed residency training in internal medicine, as well as her rheumatology fellowship, at the University of Connecticut.

Weishali V. Joshi, MD, is the section chief of rheumatology at Trinity Health of New England Medical Group, Saint Francis Hospital and Medical Center, Hartford, Conn. Dr. Joshi earned her medical degree from Grant Medical College, Mumbai. She completed residency training in internal medicine, as well as her rheumatology fellowship, at the University of Connecticut.

References

- Hekimsoy Z, Oktem IK. Serum creatine kinase levels in overt and subclinical hypothyroidism. Endocr Res. 2005;31(3):171–175.

- Madariaga MG. Polymyositis-like syndrome in hypothyroidism: Review of cases reported over the past twenty-five years. Thyroid. 2002 Apr;12(4):331–336.

- Monzani F, Caraccio N, Siciliano G, et al. Clinical and biochemical features of muscle dysfunction in subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Oct; 82(10):3315–3318.

- Sekine N, Yamamoto M, Michikawa M, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure in a patient with hypothyroidism. Intern Med. 1993 Mar;32(3):269–271.

- Scott KR, Simmons Z, Boyer PJ. Hypothyroid myopathy with a strikingly elevated serum creatine kinase level. Muscle Nerve. 2002 Jul;26(1):141–144.

- Finsterer J, Stöllberger C, Grossegger C, Kroiss A. Hypothyroid myopathy with unusually high serum creatine kinase values. Horm Res. 1999;52(4):205–208.

- Halverson PB, Kozin F, Ryan LM, Sulaiman AR. Rhabdomyolysis and renal failure in hypothyroidism. Ann Intern Med. 1979 Jul;91(1):57–58.

- Riggs JE. Acute exertional rhabdomyolysis in hypothyroidism: The result of a reversible defect in glycogenolysis? Mil Med. 1990 Apr;155(4):171–172.

- Kiernan TJ, Rochford M, McDermott JH. Simvastatin induced rhabdomyolysis and an important clinical link with hypothyroidism. Int J Cardiol. 2007 Jul 31;119(3):374–376.

- Antons KA, Williams CD, Baker SK, Phillips PS. Clinical perspectives of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis. Am J Med. 2006 May;119(5):400–409.

- Hochberg MC, Koppes GM, Edwards CQ, et al. Hypothyroidism presenting as a polymyositis-like syndrome. Report of two cases. Arthritis Rheum. 1976 Nov–Dec;19(6):1363–1366.

- Eslamian F, Bahrami A, Aghamohammadzadeh N, et al. Electrophysiologic changes in patients with untreated primary hypothyroidism. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2011 Jun;28(3):323–328.

- Mastaglia FL, Ojeda VJ, Sarnat HB, Kakulas BA. Myopathies associated with hypothyroidism: A review based upon 13 cases. Aust N Z J Med. 1988 Oct;18(6):799–806.