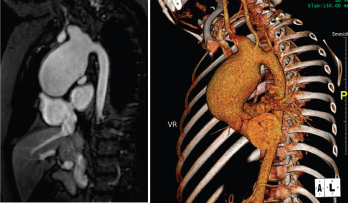

Figure 1. Large, aortic arch aneurysm as depicted by cMRI (left) and CTA (right). The aneurysm measured 4.4 x 4.9 cm at diagnosis and slowly grew over time, measuring 5.5 cm in diameter three years after diagnosis.

LAGUNA DESIGN/Science Source

A 13-year-old, adopted girl of unknown ancestry with social anxiety, selective mutism and Takayasu arteritis presented for evaluation of severe, painful, gingival hyperplasia, which limited her oral intake and resulted in weight loss.

The young patient was diagnosed with Takayasu arteritis at age 8, when she presented with a persistently elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), as high as 122 mm/hour (ref. range: 0–29 mm/hour), and a widened cardiac silhouette on chest X-ray. This was further characterized on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) as a large aneurysm of the ascending thoracic aorta measuring 4.4 x 4.9 cm (see Figure 1).

After induction therapy with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone and IV cyclophosphamide every two weeks for three months, she started maintenance therapy with prednisolone and oral methotrexate. IV infliximab was added, with favorable response, after her inflammatory markers rose during a prednisolone taper. Her inflammatory markers normalized, and she continued infliximab therapy for the next four years with good control of her disease. Attempts were made to taper infliximab, but her inflammatory markers rose each time, and she was never able to sustain serologic remission off infliximab.

Her aortic aneurysm was followed with cMRI and positron emission tomography-computer tomography (PET/CT). Repeated scans showed no evidence of active inflammation or edema, but the aneurysm slowly grew over time and three years after diagnosis, measured 5.5 cm in diameter. At that time, she began surgical evaluation for replacement of her aortic arch, but was never stable enough off medications to proceed with surgery.

Four years after diagnosis, at age 12, she was admitted to the hospital for treatment of superinfected cutaneous lesions, characterized by scaly rashes over her scalp and a papulo-pustular rash over her abdomen and trunk (see Figure 2). Several pustules were cultured and grew methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Incidentally, the rash was preceded by an episode of conjunctivitis, with no evidence of uveitis on evaluation by pediatric ophthalmology.

Figure 2: Hyperpigmented, maculopapular rash with overlying excoriation following rupture of prior pustules.

Figure 3: Hyperplastic, inflamed, erythematous and friable gingival lesions.

She was treated with IV antimicrobials during that hospital stay before being transitioned to oral antibiotics prior to discharge. Her lesions improved, and she was referred to a pediatric dermatologist as an outpatient for evaluation of possible psoriasis. Immunosuppression was held during the admission until she completed antibiotic therapy as an outpatient.

Following discharge, she developed oral thrush, gingivitis and significant oral pain. ESR and C-reactive protein (CRP) elevation persisted. She was evaluated by a pediatric dermatologist, who diagnosed a psoriaform dermatitis and prescribed topical therapies. On evaluation, the patient was also noted to have extremely erythematous and edematous gingiva, with a few shallow ulcerations at the gingival sulcus.

Her persistent gingivitis was evaluated by a pediatric dentist, who diagnosed her with juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia (JSGH), a waxing and waning condition seen most commonly in adolescent females and associated with immunodeficiency. JSGH is treated with targeted antibiotic therapy and topical steroids.

Given the concerns for concurrent immunodeficiency, infliximab was held pending an immunologic evaluation, and the patient was treated with intermittent methylprednisolone, antibiotics and topical therapies. Symptomatically, her rashes improved while she was off infliximab, and her oral lesions improved with treatment of the JSGH. A cMRI obtained during this time period showed no evidence of active vasculitis, but ESR and CRP elevation continued.

She resumed infliximab after an immunology evaluation showed no signs of immunodeficiency. ESR and CRP normalized with her resumption of infliximab, but she developed recurrent psoriaform rashes following each infusion. While the rashes initially responded to topical therapies, they worsened over time and repeatedly became superinfected, which delayed surgical replacement of her aortic arch. Because she had demonstrated no evidence of inflammation within her aortic arch since her diagnosis and the gingivitis had improved with treatment of the JSGH, infliximab was discontinued five years following diagnosis.

Three months after infliximab discontinuation, she had recurrence of severe gingivitis and oral pain. She had significant weight loss due to decreased oral intake and was admitted to the hospital three times in three months for dehydration and malnutrition.

During her first two admissions, the oral exam was remarkable for impressive gingival hyperplasia, hyperemia and persistent scalloping of her tongue (see Figure 3). No oral ulcerations were evident on examination or on upper endoscopy, but she was noted to have bilateral nasal septal ulcers. She did not have a rash. She was reevaluated for other forms of rheumatic disease, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and vasculitis, with results shown in Table 1.

| Lab | Result |

|---|---|

| ANA | negative |

| ANCA | negative |

| ACE | negative |

| Anti-Ro | 175 AU/mL (<100 AU/mL) |

| Anti-Sm, La, RNP | negative |

| Anti-dsDNA | negative |

| C3 | 130 mg/dl (86-208 mg/dL) |

| C4 | 32 mg/dL) (13-47 mg/dL) |

| Abbreviations: ANA: anti-nuclear antibody; ANCA: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; Anti-dsDNA: anti-double stranded DNA antibody; Anti-Sm: anti-Smith; RNP: anti-ribonucleoprotein. |

The patient improved during each hospitalization following the administration of oral antibiotics and low-dose prednisone, but her symptoms recurred following discharge. She displayed pill avoidance behaviors as an inpatient, and the primary concern was for superinfection of known JSGH, complicated by medication non-

adherence as an outpatient.

During her third admission, she developed frank oral and genital ulcerations, along with a cutaneous ulceration where a peripheral intravenous catheter had been previously placed (see Figure 4). Lesions were biopsied, and pathology from the left groin demonstrated a dense, superficial, mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes, histocytes and numerous neutrophils with abscess formation. An overlying epidermal ulcer and adjacent neutrophilic spongiosis with micropustules were evident. In addition, reactive dermal vessels demonstrated prominent endothelial swelling with a perivascular mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as neutrophils.