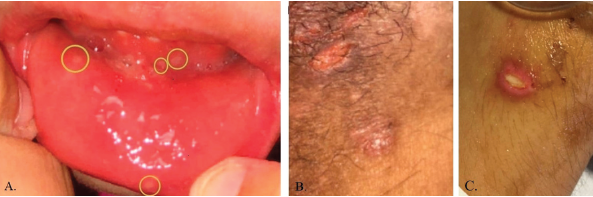

Figure 4: Pictures depicting oral ulcerations (A), genital ulceration (B) and cutaneous ulcer (C).

With these new results, the diagnosis for our patient was changed from Takayasu arteritis to Behçet’s disease with a clinical phenotype consistent with vasculo-Behçet’s.

Immunosuppression was resumed, and she was trialed on adalimumab. Unfortunately, she did not respond, and therapy was transitioned to tocilizumab. She is currently managed with monthly tocilizumab, daily azathioprine, tapering methylprednisolone and low-dose oral prednisolone. Her oral and genital ulcerations have resolved, as has her rash and gingivitis. Her inflammatory markers have normalized.

Her aortic arch has been monitored closely with cMRI and CT/PET. She did have evidence of aortic inflammation shortly after her transition to tocilizumab, which responded to an increased tocilizumab dose and addition of azathioprine. She is currently undergoing surgical evaluation for aortic arch replacement.

Discussion

First described in the 1930s, Behçet’s disease is a variable vessel vasculitis that can affect arteries or veins of any size. It was initially referred to as the triple symptom complex, referring to its classic symptoms of uveitis, and recurrent oral and genital apthosis.1,2 Although those remain the most common manifestations of the disease, other manifestations are now better understood, including cutaneous, central nervous system and gastrointestinal manifestations.

Epidemiologically, Behçet’s disease has an increased prevalence along the historical Silk Road, extending from the Mediterranean basin to eastern Asia.3 Genetic influences affecting susceptibility to Behçet’s disease are complex but the disease is most closely associated with the HLA B51 tissue antigen.1 No difference in prevalence is evident between the genders; however, male patients are likely to have more severe eye disease and increased mortality compared with female patients.1,4 Disease onset is most common in the third decade of life. Onset prior to puberty or after the sixth decade of life is rare, but does occur.4

Vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease is common, and when it is the predominant clinical feature, it is referred to as vasculo-Behcet’s.5 Vascular involvement ranges in severity from a superficial thrombophlebitis to life-threatening aneurysms. Prevalence varies among different populations and can be as high as 50% of all patients with Behçet’s disease.4,6 Although there is no difference in Behçet’s disease prevalence between the sexes, vascular lesions are consistently shown to be more common in males.6-8

Isolated venous lesions are the most common vascular lesions seen in Behçet’s disease.5,6,9 Superficial thrombophlebitis is the most common vascular manifestation, but it is classified as a cutaneous manifestation by some studies.9 If excluding superficial thrombophlebitis, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) of the lower extremities is the most frequent manifestation.6,7,9

Arterial lesions are most often aneurysmal, although stenotic and occlusive lesions are also seen.4,6 Arterial lesions often occur in combination with venous thrombosis, and isolated arterial lesions, as seen in our patient, are the least common manifestation.7,9

Femoral veins and pulmonary arteries are the most common sites of venous and arterial involvement, respectively. Other reported sites of involvement include femoral, popliteal and iliac arteries, and popliteal and iliac veins, along with the aorta, both abdominal and thoracic.7,10

A confounding feature in our patient’s presentation was the timeline of her symptom development. She developed vascular lesions five years prior to onset of classic Behçet’s symptoms. Treatment with the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor infliximab during this interval likely contributed to the delay in diagnosis; however, vascular manifestations have been reported as the presenting symptom in 15–27% of patients with vasculo-Behcet’s.6,7

Treatment for Behçet’s disease should target a patient’s primary disease manifestation.11 For vascular manifestations, immunosuppression is the cornerstone of treatment, but it is important to note that no randomized controlled trials have compared the efficacy of different treatment options.

For venous disease, azathioprine or cyclosporine may be used for superficial thrombophlebitis or thromboses of the extremities, and stronger immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide should be reserved for more severe thromboses, such as Budd-Chiari disease or those involving the vena cava.12

Anticoagulation has not been shown to be beneficial in venous disease even in the setting of DVT. This is believed to be due to the strong adherence of venous thrombi to the vessel wall in the setting of intense inflammation, leading to a low incidence of embolization in vasculo-Behcet’s.12,13

For arterial disease, more aggressive immunosuppression is recommended due to increased risk of rupture.12,13 Initial management with cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids is recommended for induction with azathioprine for maintenance therapy.12,13 Given the increased risk of rupture of

arterial aneurysms, surgical intervention is often indicated although optimal timing is controversial and the risks of rupture should be weighed against the risks of perioperative complications, such as recurrent aneurysm formation, which decrease in frequency with concurrent immunosuppression.14,15

Biologic therapy represents an emerging treatment option for both venous and arterial disease, although data is largely retrospective and limited to case series and reports. Anti-TNF therapy is the most studied and has been shown to be effective in treatment of both venous and arterial disease.16,17 Data on the efficacy of interleukin 6 inhibition is even more limited, but in a recent case series of seven patients with large-vessel involvement resistant to conventional immunosuppression, three out of the six patients who followed up in clinic achieved complete response and the other three showed partial response.18