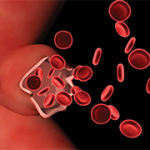

Figure 1. Large, aortic arch aneurysm as depicted by cMRI (left) and CTA (right). The aneurysm measured 4.4 x 4.9 cm at diagnosis and slowly grew over time, measuring 5.5 cm in diameter three years after diagnosis.

LAGUNA DESIGN/Science Source

A 13-year-old, adopted girl of unknown ancestry with social anxiety, selective mutism and Takayasu arteritis presented for evaluation of severe, painful, gingival hyperplasia, which limited her oral intake and resulted in weight loss.

The young patient was diagnosed with Takayasu arteritis at age 8, when she presented with a persistently elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), as high as 122 mm/hour (ref. range: 0–29 mm/hour), and a widened cardiac silhouette on chest X-ray. This was further characterized on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) as a large aneurysm of the ascending thoracic aorta measuring 4.4 x 4.9 cm (see Figure 1).

After induction therapy with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone and IV cyclophosphamide every two weeks for three months, she started maintenance therapy with prednisolone and oral methotrexate. IV infliximab was added, with favorable response, after her inflammatory markers rose during a prednisolone taper. Her inflammatory markers normalized, and she continued infliximab therapy for the next four years with good control of her disease. Attempts were made to taper infliximab, but her inflammatory markers rose each time, and she was never able to sustain serologic remission off infliximab.

Her aortic aneurysm was followed with cMRI and positron emission tomography-computer tomography (PET/CT). Repeated scans showed no evidence of active inflammation or edema, but the aneurysm slowly grew over time and three years after diagnosis, measured 5.5 cm in diameter. At that time, she began surgical evaluation for replacement of her aortic arch, but was never stable enough off medications to proceed with surgery.

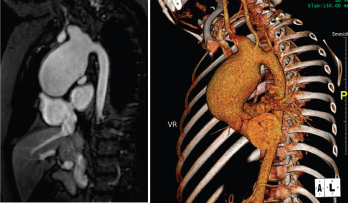

Four years after diagnosis, at age 12, she was admitted to the hospital for treatment of superinfected cutaneous lesions, characterized by scaly rashes over her scalp and a papulo-pustular rash over her abdomen and trunk (see Figure 2). Several pustules were cultured and grew methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Incidentally, the rash was preceded by an episode of conjunctivitis, with no evidence of uveitis on evaluation by pediatric ophthalmology.

Figure 2: Hyperpigmented, maculopapular rash with overlying excoriation following rupture of prior pustules.

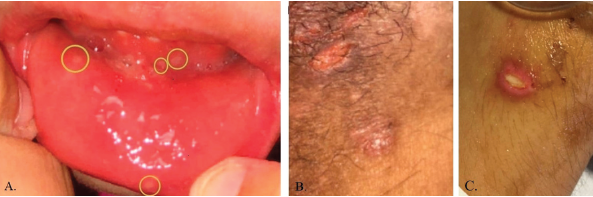

Figure 3: Hyperplastic, inflamed, erythematous and friable gingival lesions.

She was treated with IV antimicrobials during that hospital stay before being transitioned to oral antibiotics prior to discharge. Her lesions improved, and she was referred to a pediatric dermatologist as an outpatient for evaluation of possible psoriasis. Immunosuppression was held during the admission until she completed antibiotic therapy as an outpatient.

Following discharge, she developed oral thrush, gingivitis and significant oral pain. ESR and C-reactive protein (CRP) elevation persisted. She was evaluated by a pediatric dermatologist, who diagnosed a psoriaform dermatitis and prescribed topical therapies. On evaluation, the patient was also noted to have extremely erythematous and edematous gingiva, with a few shallow ulcerations at the gingival sulcus.

Her persistent gingivitis was evaluated by a pediatric dentist, who diagnosed her with juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia (JSGH), a waxing and waning condition seen most commonly in adolescent females and associated with immunodeficiency. JSGH is treated with targeted antibiotic therapy and topical steroids.

Given the concerns for concurrent immunodeficiency, infliximab was held pending an immunologic evaluation, and the patient was treated with intermittent methylprednisolone, antibiotics and topical therapies. Symptomatically, her rashes improved while she was off infliximab, and her oral lesions improved with treatment of the JSGH. A cMRI obtained during this time period showed no evidence of active vasculitis, but ESR and CRP elevation continued.

She resumed infliximab after an immunology evaluation showed no signs of immunodeficiency. ESR and CRP normalized with her resumption of infliximab, but she developed recurrent psoriaform rashes following each infusion. While the rashes initially responded to topical therapies, they worsened over time and repeatedly became superinfected, which delayed surgical replacement of her aortic arch. Because she had demonstrated no evidence of inflammation within her aortic arch since her diagnosis and the gingivitis had improved with treatment of the JSGH, infliximab was discontinued five years following diagnosis.

Three months after infliximab discontinuation, she had recurrence of severe gingivitis and oral pain. She had significant weight loss due to decreased oral intake and was admitted to the hospital three times in three months for dehydration and malnutrition.

During her first two admissions, the oral exam was remarkable for impressive gingival hyperplasia, hyperemia and persistent scalloping of her tongue (see Figure 3). No oral ulcerations were evident on examination or on upper endoscopy, but she was noted to have bilateral nasal septal ulcers. She did not have a rash. She was reevaluated for other forms of rheumatic disease, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and vasculitis, with results shown in Table 1.

| Lab | Result |

|---|---|

| ANA | negative |

| ANCA | negative |

| ACE | negative |

| Anti-Ro | 175 AU/mL (<100 AU/mL) |

| Anti-Sm, La, RNP | negative |

| Anti-dsDNA | negative |

| C3 | 130 mg/dl (86-208 mg/dL) |

| C4 | 32 mg/dL) (13-47 mg/dL) |

| Abbreviations: ANA: anti-nuclear antibody; ANCA: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; Anti-dsDNA: anti-double stranded DNA antibody; Anti-Sm: anti-Smith; RNP: anti-ribonucleoprotein. |

The patient improved during each hospitalization following the administration of oral antibiotics and low-dose prednisone, but her symptoms recurred following discharge. She displayed pill avoidance behaviors as an inpatient, and the primary concern was for superinfection of known JSGH, complicated by medication non-

adherence as an outpatient.

During her third admission, she developed frank oral and genital ulcerations, along with a cutaneous ulceration where a peripheral intravenous catheter had been previously placed (see Figure 4). Lesions were biopsied, and pathology from the left groin demonstrated a dense, superficial, mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes, histocytes and numerous neutrophils with abscess formation. An overlying epidermal ulcer and adjacent neutrophilic spongiosis with micropustules were evident. In addition, reactive dermal vessels demonstrated prominent endothelial swelling with a perivascular mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as neutrophils.

Figure 4: Pictures depicting oral ulcerations (A), genital ulceration (B) and cutaneous ulcer (C).

With these new results, the diagnosis for our patient was changed from Takayasu arteritis to Behçet’s disease with a clinical phenotype consistent with vasculo-Behçet’s.

Immunosuppression was resumed, and she was trialed on adalimumab. Unfortunately, she did not respond, and therapy was transitioned to tocilizumab. She is currently managed with monthly tocilizumab, daily azathioprine, tapering methylprednisolone and low-dose oral prednisolone. Her oral and genital ulcerations have resolved, as has her rash and gingivitis. Her inflammatory markers have normalized.

Her aortic arch has been monitored closely with cMRI and CT/PET. She did have evidence of aortic inflammation shortly after her transition to tocilizumab, which responded to an increased tocilizumab dose and addition of azathioprine. She is currently undergoing surgical evaluation for aortic arch replacement.

Discussion

First described in the 1930s, Behçet’s disease is a variable vessel vasculitis that can affect arteries or veins of any size. It was initially referred to as the triple symptom complex, referring to its classic symptoms of uveitis, and recurrent oral and genital apthosis.1,2 Although those remain the most common manifestations of the disease, other manifestations are now better understood, including cutaneous, central nervous system and gastrointestinal manifestations.

Epidemiologically, Behçet’s disease has an increased prevalence along the historical Silk Road, extending from the Mediterranean basin to eastern Asia.3 Genetic influences affecting susceptibility to Behçet’s disease are complex but the disease is most closely associated with the HLA B51 tissue antigen.1 No difference in prevalence is evident between the genders; however, male patients are likely to have more severe eye disease and increased mortality compared with female patients.1,4 Disease onset is most common in the third decade of life. Onset prior to puberty or after the sixth decade of life is rare, but does occur.4

Vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease is common, and when it is the predominant clinical feature, it is referred to as vasculo-Behcet’s.5 Vascular involvement ranges in severity from a superficial thrombophlebitis to life-threatening aneurysms. Prevalence varies among different populations and can be as high as 50% of all patients with Behçet’s disease.4,6 Although there is no difference in Behçet’s disease prevalence between the sexes, vascular lesions are consistently shown to be more common in males.6-8

Isolated venous lesions are the most common vascular lesions seen in Behçet’s disease.5,6,9 Superficial thrombophlebitis is the most common vascular manifestation, but it is classified as a cutaneous manifestation by some studies.9 If excluding superficial thrombophlebitis, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) of the lower extremities is the most frequent manifestation.6,7,9

Arterial lesions are most often aneurysmal, although stenotic and occlusive lesions are also seen.4,6 Arterial lesions often occur in combination with venous thrombosis, and isolated arterial lesions, as seen in our patient, are the least common manifestation.7,9

Femoral veins and pulmonary arteries are the most common sites of venous and arterial involvement, respectively. Other reported sites of involvement include femoral, popliteal and iliac arteries, and popliteal and iliac veins, along with the aorta, both abdominal and thoracic.7,10

A confounding feature in our patient’s presentation was the timeline of her symptom development. She developed vascular lesions five years prior to onset of classic Behçet’s symptoms. Treatment with the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor infliximab during this interval likely contributed to the delay in diagnosis; however, vascular manifestations have been reported as the presenting symptom in 15–27% of patients with vasculo-Behcet’s.6,7

Treatment for Behçet’s disease should target a patient’s primary disease manifestation.11 For vascular manifestations, immunosuppression is the cornerstone of treatment, but it is important to note that no randomized controlled trials have compared the efficacy of different treatment options.

For venous disease, azathioprine or cyclosporine may be used for superficial thrombophlebitis or thromboses of the extremities, and stronger immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide should be reserved for more severe thromboses, such as Budd-Chiari disease or those involving the vena cava.12

Anticoagulation has not been shown to be beneficial in venous disease even in the setting of DVT. This is believed to be due to the strong adherence of venous thrombi to the vessel wall in the setting of intense inflammation, leading to a low incidence of embolization in vasculo-Behcet’s.12,13

For arterial disease, more aggressive immunosuppression is recommended due to increased risk of rupture.12,13 Initial management with cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids is recommended for induction with azathioprine for maintenance therapy.12,13 Given the increased risk of rupture of

arterial aneurysms, surgical intervention is often indicated although optimal timing is controversial and the risks of rupture should be weighed against the risks of perioperative complications, such as recurrent aneurysm formation, which decrease in frequency with concurrent immunosuppression.14,15

Biologic therapy represents an emerging treatment option for both venous and arterial disease, although data is largely retrospective and limited to case series and reports. Anti-TNF therapy is the most studied and has been shown to be effective in treatment of both venous and arterial disease.16,17 Data on the efficacy of interleukin 6 inhibition is even more limited, but in a recent case series of seven patients with large-vessel involvement resistant to conventional immunosuppression, three out of the six patients who followed up in clinic achieved complete response and the other three showed partial response.18

Conclusion

Behçet’s disease is a heterogeneous vasculitis with a highly variable clinical presentation. Involvement of the large vessels is relatively rare, but may be the presenting symptom, at times preceding the onset of classic symptoms by years. In these instances, such as our own, diagnosis may be further delayed by treatment for other causes of large vessel vasculitis. Thus, it is important to consider Behçet’s disease in patients with a large-vessel vasculitis who develop new and unusual symptoms that are unexplained by their current diagnosis.

Mary Buckley, MD, is a fellow in pediatric rheumatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Jeffrey Dvergsten, MD, is an assistant professor of pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Rheumatology, Department of Pediatrics, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

References

- Ambrose NL, Haskard DO. Differential diagnosis and management of Behçet syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013 Feb;9(2):79–89.

- Zouboulis CC, Keitel W. A historical review of early descriptions of Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2002 Jul;119(1):201–205.

- Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999 Oct 21;341(17):1284–1291.

- Melikoglu M, Kural-Seyahi E, Tascilar K, Yazici H. The unique features of vasculitis in Behçet’s syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2008 Oct;35(1–2):40–46.

- Calamia KT, Schirmer M, Melikoglu M. Major vessel involvement in Behçet’s disease: An update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011 Jan;23(1):24–31.

- Fei Y, Li X, Lin S, et al. Major vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease: A retrospective study of 796 patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2013 Jun;32(6):845–852.

- Sarica-Kucukoglu R, Akdag-Kose A, Kayabal IM, et al. Vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease: A retrospective analysis of 2319 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Aug;45(8):919–921.

- Gürler A, Boyvat A, Türsen U. Clinical manifestations of Behçet’s disease: An analysis of 2147 patients. Yonsei Med J. 1997 Dec;38(6):423–427.

- Düzgün N, Ateş A, Aydintug OT, et al. Characteristics of vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006 Jan–Feb;35(1):65–68.

- Kural-Seyahi E, Fresko I, Seyahi N, et al. The long-term mortality and morbidity of Behçet syndrome: A 2-decade outcome survey of 387 patients followed at a dedicated center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003 Jan;82(1):60–76.

- Ozguler Y, Hatemi G. Management of Behçet’s syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016 Jan;28(1):45–50.

- Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Dec;67(12):1656–1662.

- Merashli M, Eid RE, Uthman I. A review of current management of vasculo-Behcet’s. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018 Jan;30(1):50–56.

- Liu Q, Ye W, Liu C, et al. Outcomes of vascular intervention and use of perioperative medications for nonpulmonary aneurysms in Behçet disease. Surgery. 2016 May;159(5):1422–1429.

- Hatemi G, Seyahi E, Fresko I, et al. One year in review 2019: Behçet’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019 Nov–Dec;37 Suppl 121(6):3–17.

- Desbois AC, Biard L, Addimanda O, et al. Efficacy of anti-TNF alpha in severe and refractory major vessel involvement of Behçet’s disease: A multicenter observational study of 18 patients. Clin Immunol. 2018 Dec;197:54–59.

- Emmi G, Vitale A, Silvestri E, et al. Adalimumab-based treatment versus disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for venous thrombosis in Behçet’s syndrome: A retrospective study of seventy patients with vascular involvement. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Sep;70(9):1500–1507.

- Ding Y, Li C, Liu J, et al. Tocilizumab in the treatment of severe and/or refractory vasculo-Behçet’s disease: A single-centre experience in China. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018 Nov 1;57(11):2057–2059.