Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune-mediated rheumatic disease characterized by multisystem involvement that can cause significant morbidity and mortality. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a rare, fulminant, autoimmune-mediated, demyelinating disease involving the white matter of the central nervous system (CNS), and is considered a manifestation of neuropsychiatric lupus.

Few reported cases involve SLE and ADEM occurring simultaneously. Some of these cases were preceded by an infection, but others had no identifiable cause. One 2015 study suggests SLE can present as ADEM, because both occur due to abnormal immune regulation.1 ADEM with lupus rarely appears in the literature, and ADEM as the initial presentation is even rarer.

We present one such case below.

Case Presentation

A 21-year-old African American male appeared in an emergency department with pain in his left calf, initially thought to be cellulitis. A few days after his initial evaluation, he was diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which was treated with apixaban.

One week later, he again required medical attention, and this time he was admitted for a 104ºF fever, chest pain and shortness of breath. A computerized tomography (CT) pulmonary angiogram performed to look for possible pulmonary embolism revealed a large pleural effusion and possible pneumonia. The patient was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics and anticoagulation medications, and discharged home when clinically stable.

Only one day after his discharge from the hospital—roughly three weeks after his initial emergency department visit—the patient developed a severe headache over the temporal area and shortly after became minimally responsive with left-side paresis. The physical exam in the emergency department noted confusion, difficulty following commands, subconjunctival and periorbital edema, and left-side paresis.

The history, obtained mostly from his family, reported the patient had not complained about recent visual changes, nausea, vomiting or diarrhea; hadn’t traveled recently; and hadn’t recently changed sexual partners. Per their best knowledge, he didn’t suffer from malar rash, photosensitivity, discoid rash, oral/nasal ulcers, hair loss, arthritis, a history of serositis (i.e., chest pain, shortness of breath and a history of pleuritis or pericarditis), renal failure, seizures or psychosis, foot or wrist drop, cranial nerve palsy, blood count drops (e.g., anemia, leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, etc.), Raynaud’s, dry mouth or dry eyes. The family also denied the patient was using any intravenous (IV) drugs or medications.

His family history was positive for possible rheumatoid arthritis and discoid lupus in the patient’s maternal grandmother.

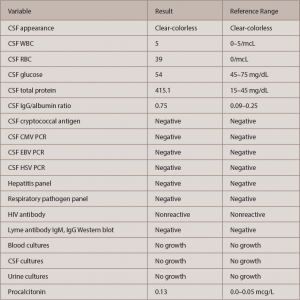

In the emergency department, a CT head scan showed subtle, low-density changes in the temporal lobes bilaterally with a lucency in the right external capsule and thalamus. A lumbar puncture (LP) followed due to initial concerns of herpes encephalitis. The LP revealed elevated protein (415.1 mg/dL) with normal glucose levels and white blood cell counts. No oligoclonal bands were present, but cerebrospinal fluid immunoglobulin G (CSF IgG) and the IgG/albumin ratio were elevated (393 mg/dL and 0.75, respectively—see Table 1). The patient was started on ceftriaxone, vancomycin and acyclovir pending culture results.

A CT chest scan revealed a large right pleural effusion. He underwent thoracentesis, and the pleural fluid analysis was exudative. A CT abdomen scan revealed mild ascites, moderate retroperitoneal edema, subcutaneous edema and external iliac adenopathy.

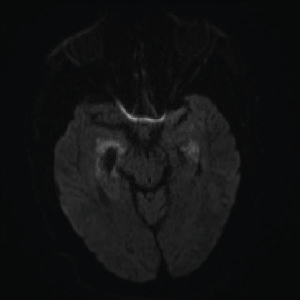

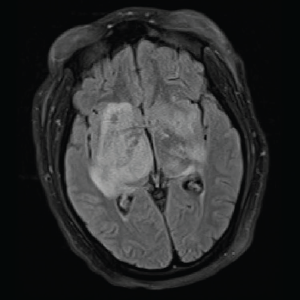

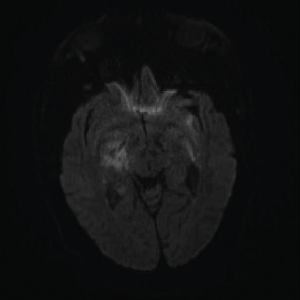

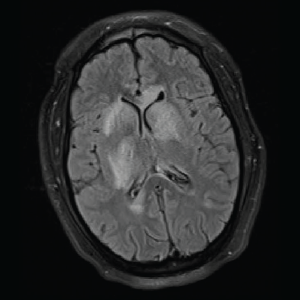

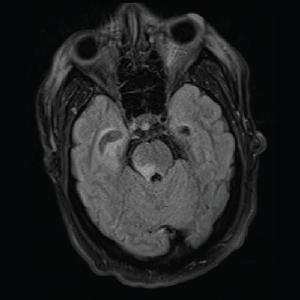

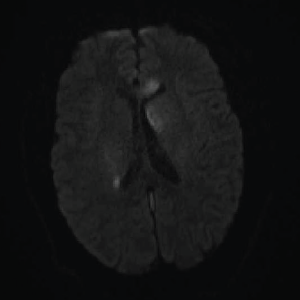

On day three of admission, the left-side weakness became profound, and the patient became unconscious. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an extensive abnormal signal with patchy areas of restricted diffusion, and a hyperintense T2/FLAIR signal throughout the bilateral mesial temporal lobes, extending to basal ganglia and to periventricular white matter with patchy hemorrhage concerning for acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (see Images 1–5).

Image 1A: DWI: Diffusion seen bilaterally, particularly in the mesial temporal lobe.

Image 1B: T2/FLAIR: Hyperintensities of the bilateral mesial temporal lobes extending into the right basal ganglia.

Image 2: DWI: Extensive abnormal signal with patchy areas of restricted diffusion, particularly in the right basal ganglia and bilateral mesial temporal lobes.

Image 3: T2/FLAIR: Hyperintensities of the caudate nucleus with mild mass effect.

Image 4: T2/FLAIR: Abnormal T2/FLAIR signal of the right midbrain and pons.

Image 5: DWI: Extensive areas of restricted diffusion extending to the periventricular white matter along the lateral ventricles.

By now a multidisciplinary team, which included infectious disease, pulmonology/critical care, rheumatology, neurology and hospitalist service, was working together to evaluate the case. They sent laboratory workup for infectious and autoimmune etiology. Complete blood count (CBC) showed normocytic anemia, lymphopenia, normal leukocytes and normal platelet counts. Inflammatory markers were elevated (ESR >130 mm/hr and C-reactive protein = 15.6 mg/dL—see Tables 1 and 2, below and opposite). A drug screen was positive for the oxycodone the patient had received a prescription for during his previous admission. Blood, urine and CSF cultures were all negative for bacterial, viral and fungal etiology (see Table 1).

Autoimmune workup revealed positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) (titer 1:640, speckled pattern). ANA subset serology identified positive SS-A, ribonucleoprotein and anti-Smith antibodies. Interestingly, double-stranded DNA (ds-DNA) and SS-B were negative (see Table 2, opposite). An antiphospholipid antibody panel was positive for elevated lupus anticoagulant, but it might have been falsely positive because the patient was already on anticoagulation with a direct thrombin inhibitor started a few weeks before this admission for DVT.

Urinalysis was positive for nephritic range proteinuria (protein in urine was 2.17 g/24 hr); hypoalbuminemia was noted (2.0 g/L) as well. Urine and serum electrophoresis were also completed, and were negative for monoclonal protein. MRI of the cervical spine and a CT angiogram of the patient’s head and neck were also completed, and showed no signs of vasculitis.

The patient’s clinical situation remained unchanged: He was nonresponsive and had severe paresis on the left side of his body. Because the infectious workup was negative, the team discontinued antibiotics.

Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with new-onset SLE with CNS involvement. Both the ACR and the SLICC Criteria for the SLE classification were met, including six ACR criteria and eight SLICC Criteria: serositis, renal disorder, neurologic disorder, hematologic disorder, ANA and immunologic disorder (i.e., ANA, anti-Smith, antiphospholipid and low complement levels).

The patient was started on IV methylprednisolone 1 g daily for five days, followed by IV cyclophosphamide at 0.75 g/m2 body surface. Following IV methylprednisolone, oral prednisone 1 mg/kg was continued. The team added hydroxychloroquine 400 mg daily shortly after.

Soon after he received this regimen, the patient’s mental status improved dramatically. After one month of physical therapy, he was able to ambulate by himself, and he featured minimal paresis on his left lower extremity. Markers of inflammation decreased to normal, and proteinuria resolved.

After six monthly IV cyclophosphamide infusions, the patient is back to normal, with no residual weakness, and he is ready to resume his job. The oral prednisone will be slowly tapered and discontinued soon. The plan: Continue the monthly therapy with cyclophosphamide up to one year, and then decrease the infusion frequency to every three months.

SLE Discussion

SLE is a severe rheumatic disease. Neuropsychiatric symptoms occur in up to two-thirds of patients and include a wide range of manifestations, including headache, cerebrovascular events, cognitive dysfunction and psychosis, as well as even more serious presentations, such as neuropathies, myelitis and encephalomyelitis.2,3 These symptoms can present alone or concomitantly with other system involvement.3

The diagnosis of neuropsychiatric lupus often proves difficult and requires a multimodal approach due to overlapping characteristics with other factors, such as infections or metabolic abnormalities. Doctors must exclude alternative explanations for the signs and symptoms.

CSF analysis, imaging data and autoimmune workup help. In up to one-third of SLE cases, CSF analysis shows increased level of protein, decreased glucose and/or lymphocytic pleocytosis. These findings, however, are neither sensitive nor specific.4,5 Roughly 20 different antibodies have been detected in neuropsychiatric lupus, and this includes anti-ribosomal P antibodies and anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor.4,5 Imaging, particularly MRI, proves especially useful, but many patients with SLE have some abnormalities detected on imaging.5

ADEM Discussion

ADEM, a fulminant demyelinating disease, is a monophasic disorder of the central nervous system. It’s rarely reported in adults. It’s most common in children because of immature myelin, the relative immaturity of the immune system and the increased frequency of infections seen in this age group.6 The incidence ranges from 0.4–0.8/100,000 per year.6,7,8,9 In approximately 30% of cases, ADEM progresses to multiple sclerosis (MS).10 Child mortality rates range from 10–30%, but most patients recover with minimal to no neurological disability.6,11,9,12

A 2015 study suggests infections trigger an immune response that causes disseminated multifocal inflammation and patchy demyelination.13 Neurologic symptoms such as fever and encephalopathy typically occur in ADEM from one to three weeks after the inciting event (which often is misleading because it resembles encephalitis) and progress rapidly.6,14 Other symptoms include weakness, ataxia, headache, meningismus, paresis, lethargy and seizures leading to coma.

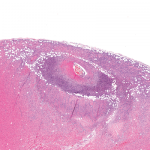

Doctors can diagnose ADEM via clinical characteristics, laboratory findings and imaging features. CSF findings are abnormal in two thirds of cases and include pleocytosis and elevated protein.11 Oligoclonal bands are typically absent. Pathologic findings show prominent perivenous demyelination with infiltrates of lymphocytes and macrophages.11 CT scans are usually abnormal but nonspecific, and may show hypodense areas within cerebral white matter and juxtacortical areas.8

MRI remains the most useful tool for diagnosing ADEM. Typical MRI findings include widespread, bilateral, asymmetric increased signal intensity on T2 weighted imaging within the white and gray matter of the brain and spinal cord.6,8

Differential diagnoses include MS, encephalitis, optic neuritis and clinical isolated syndrome.11 The International Pediatric MS Study Group has proposed diagnostic criteria to discriminate ADEM from MS, which have been validated and used widely.6,8,14

There is no standard treatment for ADEM, but once the diagnosis is made, supportive care and high-dose IV methylprednisolone (10–30 mg/kg/day, up to 1 g/day) are imperative.11 Aggressive physical and occupational therapy are also essential to successful recovery. Alternative treatments include intravenous immunoglobulin and plasma exchange.

Patients often respond favorably to steroids. In addition, doctors should initiate cyclophosphamide for neurologic manifestations of lupus.

Final Thoughts

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis as a symptom of SLE remains a rare, but unquestionably severe, neuropsychiatric symptom of SLE. Outcomes for ADEM vary widely, mostly depending on its severity. Fortunately, in the case presented here, the team made a diagnosis in a timely manner, and the patient responded well to treatment.

Today, the patient is back to his normal self and ready to restart his job.

Teresa Sosenko, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio, with an interest in rheumatology.

Teresa Sosenko, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio, with an interest in rheumatology.

Anca Emanuela Musetescu, MD, PhD, is a lecturer in rheumatology at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Craiova in Craiova, Romania.

Anca Emanuela Musetescu, MD, PhD, is a lecturer in rheumatology at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Craiova in Craiova, Romania.

Neha Gandhi, MD, is the associate program director for the Internal Medicine Residency at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, and a primary care physician.

Neha Gandhi, MD, is the associate program director for the Internal Medicine Residency at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, and a primary care physician.

Scott Friedstrom, MD, is the Internal Medicine Residency Program Director at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, and an infectious disease specialist.

Scott Friedstrom, MD, is the Internal Medicine Residency Program Director at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, and an infectious disease specialist.

Diana Girnita, MD, PhD, is a rheumatologist and faculty for internal medicine at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati.

Diana Girnita, MD, PhD, is a rheumatologist and faculty for internal medicine at Trihealth Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati.

References

- Kim JM, Son CN, Chang HW, et al. Simultaneous presentation of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) after enteroviral infection: Can ADEM present as the first manifestation of SLE? Lupus. 2015 May;24(6): 633–637.

- Bermejo PE, Ruiz A, Beistegui M, et al. Hemorrhagic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis as first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Neurol. 2008 Aug;255(8):1256–1258.

- Klippel JH, Stone JH, Crofford LJ, et al. (2008) Primer on the Rheumatic Disease. New York, New York: Springer.

- Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, et al. (2013) Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier Saunders.

- Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al. (2011) Rheumatology. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby Elsevier.

- Rahmlow MR, Kantarci O. Fulminant demyelinating diseases. Neurohospitalist. 2013 Apr;3(2):81–91.

- Wang PN, Fuh JL, Liu HC, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in middle-aged or elderly patients. Eur Neurol. 1996;36(4):219–223.

- Marin SE, Callen DJ. The magnetic resonance imaging appearance of monophasic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: An update post application of the 2007 consensus criteria. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2013 May;23(2):245–266.

- Zettl UK, Stuve O, Patejdl R. Immune-mediated CNS diseases: A review on nosological classification and clinical features. Autoimmun Rev. 2012 Jan;11(3):167–173.

- de Seze J, Debouverie M, Zephir H, et al. Acute fulminant demyelinating disease: A descriptive study of 60 patients. Arch Neurol. 2007 Oct;64(10):1426–1432.

- Alexander M, Murthy JM. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: Treatment guidelines. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011 Jul;14(Suppl 1);S60–S64.

- Honkaniemi J, Dastidar P, Kahara V, et al. Delayed MR imaging changes in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001 Jun–Jul;22(6):1117–1124.

- Borras-Novell C, García Rey E, Perez Baena LF, et al. Therapeutic plasma exchange in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children. J Clin Apher. 2015 Dec;30(6):335–339.

- Likasitwattanakul S, Chiewvit P. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in Siriraj Hospital: Clinical manifestations and short-term outcome. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012 Mar;95(3):391–396.