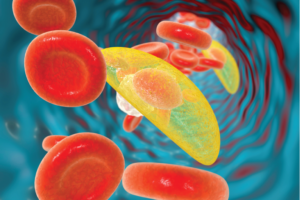

Toxoplasma gondii parasites in blood, the causative agent of toxoplasmosis disease, 3D illustration

Kateryna Kon / shutterstock.com

The occurrence of opportunistic infections is an established complication in patients diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The foremost challenge in such circumstances is differentiating between an exacerbation or progression of SLE, and the effects of the infection itself.1 Toxoplasma gondii is a ubiquitous parasite that often causes an asymptomatic infection in healthy, immunocompetent adults. However, in the setting of an immunocompromised status, such as SLE or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), toxoplasmosis can become symptomatic and cause various, grave consequences, including cerebritis.2

Case Presentation

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a few hours of altered mental status, right facial droop and slurred speech. She had recently been diagnosed with SLE based on the presence of malar rash, discoid lesions, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, arthritis and a positive ANA. Immunosuppressive therapy had not been initiated.

She had been tired and suffering from memory loss for the past week. She denied having a headache, neck stiffness, vision changes, fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, urinary or bowel changes. She also denied alcohol or drug use. A physical exam was pertinent for confusion and an inability to follow commands. Cardiovascular and pulmonary exams were normal.

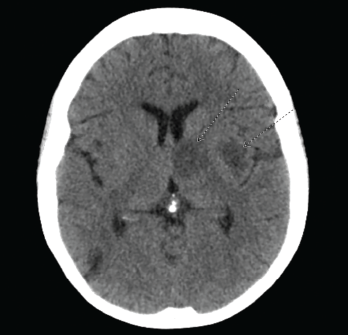

The initial computed tomography (CT) scan of the head revealed multiple bihemispheric regions of hypodensity, as well as evidence of remote multifocal cortical and subcortical infarcts (see Figure 1). Based on the initial presentation and CT findings, the preliminary differential diagnosis included ischemic or embolic stroke, and lupus cerebritis.

Figure 1. CT of the head reveals multiple bihemispheric regions of hypodensity, as well as evidence of remote multifocal cortical and subcortical infarcts

The initial laboratory evaluation was within normal limits, with the exception of an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 12,800 cells/µL and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 20 mg/L (normal: <3 mg/L). The initial immunological evaluation revealed an elevated anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 2,560. Anti-double-stranded DNA antibody and anti-cardiolipin antibody were not detected, and complement C3 and C4 were normal.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed innumerable enhancing lesions scattered throughout the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres, with involvement of the cortex, subcortical and periventricular white matter, bilateral basal ganglia, thalami and brainstem, with target and nodular enhancement (see Figure 2).

Given the elevated WBC and CRP levels, along with the MRI findings, our differential diagnoses now included cerebral toxoplasmosis, neurocysticercosis and central nervous system lymphoma. An initial cerebrospinal fluid analysis did not reveal any significant findings. However, subsequent cerebrospinal fluid analysis for Toxoplasma revealed 2,600 copies/mL. Serologies were negative for HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B and hepatitis C. T. gondii IgG was positive (145 IU/mL; normal 0.0–7.1 IU/mL). T. gondii IgM was normal.