Toxoplasma gondii parasites in blood, the causative agent of toxoplasmosis disease, 3D illustration

Kateryna Kon / shutterstock.com

The occurrence of opportunistic infections is an established complication in patients diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The foremost challenge in such circumstances is differentiating between an exacerbation or progression of SLE, and the effects of the infection itself.1 Toxoplasma gondii is a ubiquitous parasite that often causes an asymptomatic infection in healthy, immunocompetent adults. However, in the setting of an immunocompromised status, such as SLE or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), toxoplasmosis can become symptomatic and cause various, grave consequences, including cerebritis.2

Case Presentation

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a few hours of altered mental status, right facial droop and slurred speech. She had recently been diagnosed with SLE based on the presence of malar rash, discoid lesions, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, arthritis and a positive ANA. Immunosuppressive therapy had not been initiated.

She had been tired and suffering from memory loss for the past week. She denied having a headache, neck stiffness, vision changes, fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, urinary or bowel changes. She also denied alcohol or drug use. A physical exam was pertinent for confusion and an inability to follow commands. Cardiovascular and pulmonary exams were normal.

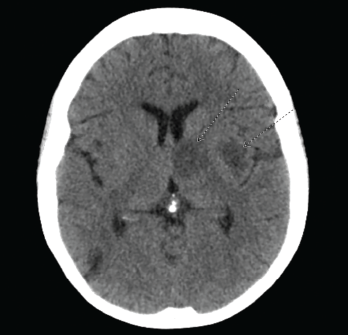

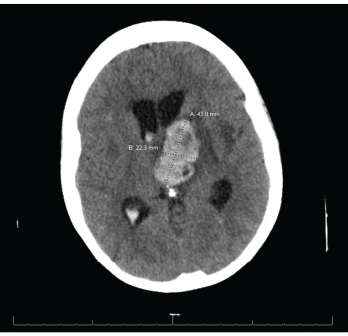

The initial computed tomography (CT) scan of the head revealed multiple bihemispheric regions of hypodensity, as well as evidence of remote multifocal cortical and subcortical infarcts (see Figure 1). Based on the initial presentation and CT findings, the preliminary differential diagnosis included ischemic or embolic stroke, and lupus cerebritis.

Figure 1. CT of the head reveals multiple bihemispheric regions of hypodensity, as well as evidence of remote multifocal cortical and subcortical infarcts

The initial laboratory evaluation was within normal limits, with the exception of an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 12,800 cells/µL and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 20 mg/L (normal: <3 mg/L). The initial immunological evaluation revealed an elevated anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 2,560. Anti-double-stranded DNA antibody and anti-cardiolipin antibody were not detected, and complement C3 and C4 were normal.

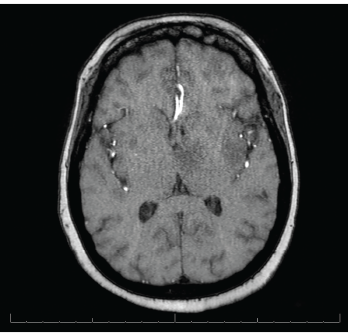

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed innumerable enhancing lesions scattered throughout the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres, with involvement of the cortex, subcortical and periventricular white matter, bilateral basal ganglia, thalami and brainstem, with target and nodular enhancement (see Figure 2).

Given the elevated WBC and CRP levels, along with the MRI findings, our differential diagnoses now included cerebral toxoplasmosis, neurocysticercosis and central nervous system lymphoma. An initial cerebrospinal fluid analysis did not reveal any significant findings. However, subsequent cerebrospinal fluid analysis for Toxoplasma revealed 2,600 copies/mL. Serologies were negative for HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B and hepatitis C. T. gondii IgG was positive (145 IU/mL; normal 0.0–7.1 IU/mL). T. gondii IgM was normal.

Figure 2. MRI of the brain shows innumerable enhancing lesions scattered throughout the bilateral cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres.

The patient was treated with 1,500 mg of sulfadiazine every six hours, 75 mg of pyrimethamine daily and 25 mg of leucovorin daily, intended for a course of four to six weeks. During her course of treatment, the patient became unresponsive and an emergent head CT revealed a large, left thalamic, intraparenchymal hemorrhage with intraventricular extension causing obstructive hydrocephalus (see Figure 3). A neurosurgeon was consulted.

The patient required intubation and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). During her ICU stay, the patient had two episodes of tonic-clonic seizures and was started on 500 mg of levetiracetam every 12 hours.

The patient underwent an electroencephalogram, which exhibited diffuse slowing, including frequent generalized rhythmic delta activity, suggesting a moderate degree of bilateral cerebral dysfunction and independent left-hemispheric slowing, temporal maximum, suggesting focal cerebral dysfunction in that region.

Despite aggressive measures, including placement of an external ventricular drain, the neurological status of the patient deteriorated, and the patient died one week following her admission.

The patient’s family declined a brain biopsy.

Discussion

Figure 3. CT reveals a large left thalamic intraparenchymal hemorrhage with intraventricular extension causing obstructive hydrocephalus.

SLE patients are at risk of developing numerous bacterial, viral and parasitic infections secondary to an inherent immunocompromised state.

Opportunistic infections are an established complication of SLE, with an incidence of up to 50%. Studies indicate these infections may involve the skin, nervous system, respiratory system and urinary tract.3-7 One such study, involving more than 33,000 patients with SLE, found an incidence of 10.8 serious infections per 100 person-

years.8 Although the majority of these infections can be attributed to bacteria, viral and parasitic infections are increasingly common, including infections caused by Epstein-Barr virus, human papillomavirus, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19 and the parasite T. gondii.7

Risk factors that predispose SLE patients to infections include being male and Black, longer duration of disease, SLE flare, lupus nephritis, reduction in cell counts (e.g., lymphocytes and neutrophils) and the use of immunosuppressants.7,8 Of note, none of the aforementioned risk factors was present in our patient.

T. gondii is a common opportunistic parasite causing infection in both humans and animals, with the most common course being asymptomatic infection with chronic latency. Neurologic manifestations are commonly seen in congenital infections and immunocompromised patients, and include seizures, hydrocephalus, spasticity, nerve palsies and vision impairment.

The diagnosis of cerebral toxoplasmosis can be established by the presence of a compatible clinical presentation, suggestive brain imaging or detection of T. gondii DNA on polymerase chain reaction of the cerebrospinal fluid.9,10

Although our patient’s clinical presentation was not specific, MRI findings of multiple enhancing lesions, along with an IgG antibody of 145 IU/mL, were highly suggestive of cerebral toxoplasmosis; this diagnosis was subsequently confirmed by PCR of the cerebrospinal fluid, which confirmed the presence of T. gondii. Additionally, the patient’s CRP was elevated at 20 mg/L (normal 0–5 mg/L), also pointing toward an infectious etiology.

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis of the patient in our case report was unremarkable, with no inflammatory changes or pleocytosis. Research suggests cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities are present in 32% of SLE patients with neuropsychiatric illness.11

Additional techniques proposed to elucidate the diagnosis of toxoplasmosis include demonstration of the organism in body fluids or tissues via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, rapid electron microscopy, polymerase chain reaction and Wright-Giemsa stained slides.12

A known complication of cerebral involvement in SLE patients is seizures, including grand mal, petit mal, Jacksonian epilepsy and temporal lobe epilepsy.13,14 The patient in question demonstrated seizures of tonic-clonic type. Our patient also developed hydrocephalus, which is frequently associated with cerebral toxoplasmosis.

Conclusion

It can be challenging to diagnose central nervous system infections in SLE patients presenting with non-specific neurological manifestations. Opportunistic infections, such as cerebral toxoplasmosis, should be kept in mind in addition to the more obvious diagnosis of lupus cerebritis and ischemic/embolic stroke when dealing with SLE patients presenting with altered mental status. When suspected, imaging, such as CT and MRI of the brain, and serological testing should be pursued—particularly if symptoms don’t improve with immunosuppressive therapy.

Komal Ejaz, MD, is a resident in internal medicine at the Wright Center for Graduate Medical Education, Scranton, Pa.

Komal Ejaz, MD, is a resident in internal medicine at the Wright Center for Graduate Medical Education, Scranton, Pa.

Muhammad Ali Raza, MD, is a resident in internal medicine at Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center/Temple University, Johnstown, Pa.

Muhammad Ali Raza, MD, is a resident in internal medicine at Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center/Temple University, Johnstown, Pa.

References

- Jung JY, Suh CH. Infection in systemic lupus erythematosus, similarities, and differences with lupus flare. Korean J Intern Med. 2017 May;32(3):429–438.

- Lyngberg KK, Vennervald BJ, Bygbjerg IC, et al. Toxoplasma pericarditis mimicking systemic lupus erythematosus. Diagnostic and treatment difficulties in one patient. Ann Med. 1992 Oct;24(5):337–340.

- Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 10-year period: A comparison of early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003 Sep;82(5):299–308.

- Zhou W, Yang CD. The causes and clinical significance of fever in systemic lupus erythematosus: A retrospective study of 487 hospitalised patients. Lupus. 2009 Aug;18(9):807–812.

- Nived O, Sturfelt G, Wollheim F. Systemic lupus erythematosus and infection: A controlled and prospective study including an epidemiological group. Q J Med. 1985 Jun;55(218):271–287.

- Hidalgo-Tenorio C, Jiménez-Alonso J, de Dios Luna J, et al. Urinary tract infections and lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004 Apr;63(4):431–437.

- Cuchacovich R, Gedalia A. Pathophysiology and clinical spectrum of infections in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009 Feb;35(1):75–93.

- Feldman CH, Hiraki LT, Winkelmayer WC, et al. Serious infections among adult Medicaid beneficiaries with systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Jun;67(6):1577–1585.

- Luft BJ, Remington JS. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1992 Aug;15(2):211–222.

- Cohn JA, McMeeking A, Cohen W, et al. Evaluation of the policy of empiric treatment of suspected Toxoplasma encephalitis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1989 May;86(5):521–527.

- Mok CC, Lau CS, Yuen KY. Cryptococcal meningitis presenting concurrently with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1998 Mar-Apr;16(2):169–171.

- Zamir D, Amar M, Groisman G, et al. Toxoplasma infection in systemic lupus erythematosus mimicking lupus cerebritis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999 Jun;74(6):575–578.

- Rothfield N. Clinical aspects and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1989 Oct;1(3):327–331.

- Feinglass EJ, Arnett FC, Dorsch CA, et al. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: Diagnosis, clinical spectrum, and relationship to other features of the disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976 Jul;55(4):323–339.