Lan Chen, MD, PhD, believes celiac disease is vastly more common than current diagnostic tests indicate, and she hopes rheumatologists can take the lead on research into the disease. At least 3 million people in the U.S. are living with celiac disease. According to celiac disease statistics from the University of Chicago School of Medicine Celiac Disease Center, 97% of them are undiagnosed.1 Data suggest 34% of patients diagnosed with celiac disease at or after age 20 will develop another autoimmune disease.2

Lan Chen, MD, PhD, believes celiac disease is vastly more common than current diagnostic tests indicate, and she hopes rheumatologists can take the lead on research into the disease. At least 3 million people in the U.S. are living with celiac disease. According to celiac disease statistics from the University of Chicago School of Medicine Celiac Disease Center, 97% of them are undiagnosed.1 Data suggest 34% of patients diagnosed with celiac disease at or after age 20 will develop another autoimmune disease.2

“When patients come to us with advanced stages of autoimmune disorders, we need to test for celiac as a practice standard,” Dr. Chen says.

In her rheumatology practice, Dr. Chen sees a number of patients with non-specific autoimmune conditions, such as arthritis, thyroid imbalance, Hashimoto, psoriasis, irritable bowel and vitamin deficiencies, as well as advanced autoimmune diseases, such as lupus and fibromyalgia. She finds these patients often have a diagnosis of celiac disease or a family history of it and believes they can benefit from a gluten-free diet based on research and anecdotal cases.3

“If we are treating advanced autoimmune diseases only with immunosuppressants, we are doing a disservice to patients who may have celiac and could benefit considerably from a diet targeted to avoid gluten,” Dr. Chen says.

Science of Celiac

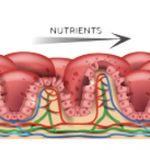

People with celiac disease have a sensitivity to gluten—a protein found in wheat, rye and barley.4 When a person with celiac ingests gluten, it triggers an immune response that attacks the small intestine, damaging the villi responsible for nutrient absorption, as well as other autoimmune mediated damages to the pancreas, thyroid, liver, adrenal glands, synovial tissues, nerves, salivary glands, muscles, skin and kidney. Celiac disease is more frequent in those who have the following autoimmune conditions: Type I diabetes (2.4–16.4%), multiple sclerosis (11%), Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (4–6%), autoimmune hepatitis (6–15%), Addision’s disease (6%), arthritis (1.5–7.5%), Sjögren’s syndrome (2–15%), idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (5.7%) and IgA nephropathy (3.6%).

Dr. Chen worries about nutrient deficiencies in both diagnosed and undiagnosed patients with celiac disease. The disease causes the malabsorption of important nutrients, such as vitamins and minerals. Living with gluten sensitivity herself, Dr. Chen notes that completely avoiding gluten can sometimes be a challenge. “A patient has to be very educated and motivated to maintain a strict gluten-free diet,” she says.

Much like other treatments targeted to reduce immune response, a noticed difference in improved health on a gluten-free diet can take up to six or even 12 months to become evident, and rheumatologists should explain this to their patients. Dr. Chen explains, “Patients may give up on a gluten-free diet or cheat if they don’t see immediate results, which sets them back to square one in seeing a noticeable health improvement.”