The results of the phase I/II trials and registered case reports have been published.2 In essence, two publications have shown that around 50% of SLE patients achieved remission at some stage post-transplant,4,5 and, in MS and SSc, durable remission occurred in one-third. (See Figure 3, p. 22.) Transplant-related mortality was highest in the multicenter SLE series, but in general, that is now less, due to more stringent patient selection.

In SSc, it has been recently shown that HSCT is not just a once-only immunosuppression. HSCT also seems to be able to reverse fibrosis6,7 and improve micro-vascularisation.8,9

A prospective trial called the Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation International Scleroderma trial (ASTIS) is nearing completion in Europe, comparing HSCT with 12 monthly cyclophosphamide IVI pulses; in the United States, the Scleroderma Cyclophosphamide or Transplant (SCOT) trial is running. Both have similar designs with the exception of the treatment arm of SCOT, which includes limited radiotherapy.

Limited experience is available with allogeneic HSCT for autoimmune disease.10 Although offering the theoretical advantage of a “healthy” immune system, the real risk of GvHD and its attendant morbidity and mortality has limited this form of HSCT to small series and case reports.

The Future of HSCT for Autoimmune Disease

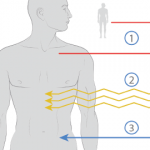

There are now significant data suggesting that a profound immunoreduction supported by autologous stem cell rescue may alter the natural history of some autoimmune disease, with most experience being in SSc. The initial treatment is hazardous, with potentially lethal complications such as cardiotoxicity or overwhelming infection.

So far, however, there is no indication that unknown toxicity occurs in autoimmune disease patients. The considerable toxicity of HSCT in general is the reason that the treatment should only be performed in experienced transplant units. When selecting a patient for such a treatment, one should ask the following questions:

- Is the disease potentially more dangerous than the treatment? (Current estimates are around 5% transplant-related mortality.)

- Is the patient in too advanced a state of vital organ damage such that the chances of meaningful benefit are outweighed by the higher risk of transplant-related mortality (e.g., advanced lung fibrosis with diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide of less than 30% predicted)?

- Does the patient and his or her family understand that the stem-cell transplant is only to “rescue the normal blood cells” after heavy immunoablation and not to supply some special healing action on the diseased organs?

- Have you exhausted the existing conventional proven treatments for this autoimmune disease?

If the answers to these questions are affirmative, then it is reasonable to enter such a patient into one of the experimental trials. Only through prospective randomized trials are hematologists able to offer long-term cure to certain leukemia patients, even though the exact cause of leukemia remains unknown.