In the past several years, Chikungunya has emerged as a dangerous, rapidly spreading viral illness characterized mainly by debilitating arthritic symptoms. Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a single-stranded RNA virus of the genus Alphavirus. The virus is transmitted to humans by mosquitoes. The virus was first isolated from the serum of a febrile patient during an outbreak that occurred in the southern province of Tanzania (Makonde Plateau) in 1952–1953.1,2 The name Chikungunya translates in the Bantu language of the Makonde people to “that which bends up,” in reference to the stooped posture patients frequently adopt due to the frequent and incapacitating associated joint pain. Although initially limited to tropical Africa, South East Asia and the Indian Ocean islands, Chikungunya has spread to Europe and also, recently, to the American continents.3,4

Unlike most other viruses, CHIKV predominantly attacks the joint, and patients present with features similar to inflammatory arthritis. A period of persistent joint symptoms often follows the acute febrile phase, which is indeed difficult to distinguish from rheumatoid arthritis. Many of these cases get referred to rheumatologists, and thus, it’s important to create awareness about arthritis caused by CHIKV. This article describes the risk associated with the spread of this infection and clinical features, mainly focusing on rheumatic manifestations.

How Far Has This Viral Infection Spread?

Although there have been reports of epidemics with fevers and predominant arthritis symptoms in the early 19th century, they were thought to be dengue fever. But it’s now felt they would better fit the presentation of Chikungunya infection.5 Since 1952, Chikungunya has been frequently reported in the African continent, and the first reported outbreak in Asia was in Thailand in 1958. Since then, a number of cases were reported from 1960 to 2000 in Africa and Asia.6,7

But it was in 2005 when this viral outbreak caught global attention with the rapid spread of devastating outbreaks in the Indian Ocean islands. It was most notable in the Reunion Islands, affecting around 266,000 individuals (34% of the island’s population) and 75% of the population of Lamu (an island off the coast of Kenya).8,9 The French Territories in the Indian Ocean had more extensive administrative and technological resources than other islands in the region, so they had better local epidemic-monitoring systems. In India, nearly 1.4 million suspected cases of Chikungunya were reported in 2006.10,11

Although considered a tropical disease, an outbreak of Chikungunya occurred in northeastern Italy in 2007, resulting in more than 200 locally acquired cases.12 The index case was a traveler returning to Europe from India. Phylogenetic analysis of the virus demonstrated similarity with the Chikungunya strain found in the Indian Ocean outbreaks. This is an example for seasonal synchrony in which the period of active transmission in India coincided with Italy’s hottest months. It shortened the extrinsic incubation period, resulting in the early transmission of the virus to a new host.

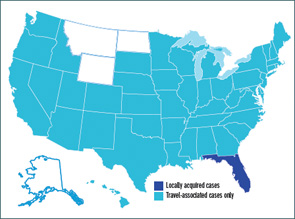

In December 2013, Chikungunya infection was reported in the Caribbean Island of Saint Martin, and by April 2014, it had spread to 14 nearby countries. In the U.S., 1,211 Chikungunya cases had been reported to ArboNET (a national surveillance system for arboviral diseases) as of Sept. 30, 2014, of which 40% of the cases were reported from New York and Florida. Alarmingly, 11 locally transmitted cases have been reported from Florida since mid-July 2014. This infection has been reported more widely in Puerto Rico, with around 466 locally transmitted cases reported (see Figure 1).

How Is Chikungunya Transmitted?

The two most common CHIKV vectors are Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, although there have been rare isolation of other Aedes (Ae.) mosquitoes with transmission of CHIKV (see Figure 2).

Ae.aegypti is widely distributed in urban areas of the tropics and subtropics. They are found in a perimeter range of 100 meters of human habitation and breed readily in flowerpots and discarded cups. On the other hand, Ae.albopictus (the so-called Asian tiger mosquito) colonizes more around peridomestic habitats, such as farms with a lot of vegetation. It is one of the most invasive mosquitoes in the world and an aggressive daytime human biter. The large outbreaks of Chikungunya in Italy and Reunion have resulted from virus transmission by Ae.albopictus. In fact, CHIKV and dengue virus share the same mosquito vector species, so epidemic waves caused by both viruses affect the same regions, and human co-infections may occur.

Viral Strains

CHIKV has three major phylogroups based on the viral envelope E1 structural glycoprotein sequence: East-Central South Africa (ECSA), West African and the Asian strain. A fourth strain, called the Indian Ocean strain, which is a variant of the ECSA group, has a genetic change with a substitution of an alanine to valine at position 226 of the E1 envelope glycoprotein (E1-A226V).15,16 This point mutation has enhanced both virus replication and transmission efficacy in Ae.albopictus and was observed in >90% of viral sequences in the Indian Ocean outbreaks.17

Ae.aegypti is more capable of transmitting the ESCA and Asian strains, and the Ae.albopictus efficiently transmits the epidemic Indian Ocean strain. The CHIKV strain isolated from the recent outbreak in the Caribbean belongs to a variant of the Asian genotype, which is primarily transmitted by Ae.aegypti.18 Being more abundant in the Americas than Ae.albopictus, Ae.aegypti represents a real threat.19-22

Clinical Manifestations

Chikungunya infection has two successive phases. After an incubation period of around two to four days (range one to 14), the initial phase of acute illness typically presents with high-grade fevers, skin rash and characteristic severe polyarthritis. Unlike most other alphaviral infections, Chikungunya is associated with high-grade fever (often exceeding 39ºC). Forty to 60% of patients have a macular or maculopapular rash (usually three days after fever), which starts on the limbs, can involve the face and may be patchy or diffuse. The skin lesions are pruritic, and exfoliative dermatitis is common. Bullous skin lesions have also been described, most often in children. Additional common manifestations in the acute phase are headache, conjunctivitis, myalgia, peripheral lymphadenopathy, neuropathy and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Polyarthritis is reported in 87–98% of cases, typically seen two to five days after onset of fever. They are commonly symmetrical (64–73%), with pain and swelling involving distal small joints such as those of the hands, wrists and ankles. Involvement of the axial skeleton was noted in 34–52% of cases.8,23,24 Often, the arthritis is severe and debilitating, leading to immobilization due to pain. The subsequent phase of persistent arthritis/arthralgias is unique with Chikungunya. This phase is characterized by morning stiffness, persistent joint pain and swelling, which may last for months to years. One study from South Africa reports arthritis occurring eight years after the acute illness.25 The number of individuals with persistent joint symptoms decreases with time.

These symptoms mimic rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and case reports from the Reunion Island outbreak have reported 21 patients fulfilling the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for RA.26 Another study from India showed 36% (34/94) met the ACR criteria for RA, of whom only one individual tested positive for anticyclic citrullinated peptide.27 Tenosynovitis is another commonly described feature.28 Lymphopenia and moderate thrombocytopenia are observed on laboratory tests. An elevated sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein is not frequently seen. A small number of cases from India, as well as the Reunion Islands, has documented radiographic erosions on magnetic resonance imaging during the persistent arthritic phase.27,28

Can Chikungunya Infection Be Fatal?

Severe complications and death are reported among patients older than 65 years, infants and in those with other underlying co-morbid illnesses. A case–fatality ratio of about 1:1,000 was documented from the Reunion Islands.29 Uveitis, myocarditis, hepatitis, nephritis, meningoencephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome and cranial nerve palsies have also been reported with Chikungunya infection.6,8,30,31 Thus, chances for severe complications are higher in immunocompromised individuals. There has not been any clear report about Chikungunya in immunosuppressed individuals, but it would be concerning in those who are on immunosuppressive treatment. In utero transmission has been documented, mostly during the second trimester, as well as intrapartum transmission. In a case report from the Reunion Islands, severe illness was observed in 53% of newborns and mainly consisted of encephalopathy with persistent disabilities in 44% of them.32

How to Diagnose Chikungunya?

The primary diagnostic tool is testing for IgM anti-Chikungunya virus antibodies (by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]). They are detected in the serum starting about four days following onset of symptoms. IgG antibodies are detected after about two weeks and may persist for years. CHIKV diagnostic testing in the U.S. is primarily only performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Testing for these antibodies is not very specific, and cross-reactivity with other alphaviruses has been noted. Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) can be used as a diagnostic tool during the initial viremic phase (≤8 days). Viral cultures are used as a research tool and may detect the virus in the first three days of illness. CHIKV has been isolated from biopsies of skeletal muscles, synovial tissue and skin, and has also been found in perivascular synovial macrophages.33

Treatment

There has not been much evidence-based research regarding treatment of Chikungunya-related arthritis. The mainstay of treatment in the acute phase is supportive measures with fluids and antiinflammatory agents (nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]). Some drugs were found to be effective against CHIKV when tested in vitro, but no antiviral agents have been shown to be effective in human infections.34 There has been documentation of persistence of the virus in nonhuman primates weeks after infection,35 and thus, the use of immunosuppressive agents would not be advised. There are also reports of strong rebound arthritis when corticosteroid treatment is stopped.6

There has been only anecdotal evidence for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in the chronic arthritic phase. A single, randomized, controlled study, comparing chloroquine with NSAIDs (meloxicam), failed to demonstrate any advantage of chloroquine over meloxicam.36

Active research is underway to develop a better vaccine and treatments for Chikungunya infection. Currently, prevention consists of minimizing mosquito exposure.

Conclusion

Chikungunya continues to spread to different geographic areas and is a major threat with its ability to rapidly infect a large population. The debilitating severe chronic arthritis, which can present in a similar fashion to RA, is a serious concern for rheumatologists. In the U.S., the vectors transmitting dengue virus are only seen in the southern and southeastern states, but it has been demonstrated in the lab that it does not take long for viral mutation and mosquito adaptability to occur. Better understanding of the pathophysiogenesis is needed for developing treatment and preventive strategies. More randomized, controlled studies are needed to guide treatment approaches.

Dany V. Thekkemuriyil, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Washington University in St. Louis. He saw Chikungunya during the outbreak in India.

Chikungunya—Things to Note

- Acute presentation is characterized by high-grade fevers, joint pain, rash.

- Chronic persistent arthritis lasting months to years, which can present similar to RA.

- Travel history and history of sick contacts is important.

- Report suspected cases to the state or local health department.

- Laboratory diagnosis: Serology to detect IgMif ≥4 days, IgG >2 weeks since onset (CDC). RT-PCR to detect viral RNA if in first week of illness.

- Supportive treatment: fluids, analgesics, NSAIDs.

References

- Robinson MC. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. I. Clinical features. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955 Jan;49(1):28–32.

- Lumsden WH. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. II. General description and epidemiology. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955 Jan;49(1):33–57.

- Fischer M, Staples JE; Arboviral Diseases Branch, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC. Chikungunya virus spreads in the Americas—Caribbean and South America, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014 Jun 6;63(22):500–501.

- Vega-Rua A, Zouache K, Girod R, et al. High level of vector competence of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from ten American countries as a crucial factor in the spread of Chikungunya virus. J Virol. 2014 Jun;88(11):6294–6306.

- Carey DE. Chikungunya and dengue: A case of mistaken identity? J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1971 Jul;26(3):243–262.

- Thiberville SD, Moyen N, Dupuis-Maguiraga L, et al. Chikungunya fever: Epidemiology, clinical syndrome, pathogenesis and therapy. Antiviral Res. 2013 Sep;99(3):345–370.

- Staples JE, Breiman RF, Powers AM. Chikungunya fever: An epidemiological review of a re-emerging infectious disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Sep 15;49(6):942–948.

- Renault P, Solet JL, Sissoko D, et al. A major epidemic of chikungunya virus infection on Reunion Island, France, 2005–2006. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007 Oct;77(4):727–731.

- Sergon K, Njuguna C, Kalani R, et al. Seroprevalence of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection on Lamu Island, Kenya, October 2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008 Feb;78(2):333–337.

- Chopra A, Anuradha V, Lagoo-Joshi V, et al. Chikungunya virus aches and pains: An emerging challenge. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Sep;58(9):2921–2922.

- Krishnamoorthy K, Harichandrakumar KT, Krishna Kumari A, et al. Burden of chikungunya in India: Estimates of disability adjusted life years (DALY) lost in 2006 epidemic. J Vector Borne Dis. 2009 Mar;46(1):26–35.

- Charrel RN, de Lamballerie X, Raoult D. Seasonality of mosquitoes and chikungunya in Italy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008 Jan;8(1):5–6.

- Rulli NE, Suhrbier A, Hueston L, et al. Ross River virus: Molecular and cellular aspects of disease pathogenesis. Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Sep;107(3):329–342.

- Pialoux G, Gauzere BA, Jaureguiberry S, et al. Chikungunya, an epidemic arbovirosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007 May;7(5):319–327.

- Bordi L, Carletti F, Castilletti C, et al. Presence of the A226V mutation in autochthonous and imported Italian chikungunya virus strains. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Aug 1;47(3):428–429.

- Schuffenecker I, Iteman I, Michault A, et al. Genome microevolution of chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS Med. 2006 Jul;3(7):e263.

- Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, et al. A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog. 2007 Dec;3(12):e201.

- Vega-Rua A, Zouache K, Girod R, et al. High level of vector competence of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from ten American countries as a crucial factor in the spread of Chikungunya virus. J Virol. 2014 Jun;88(11):6294–6306.

- Devaux CA. Emerging and re-emerging viruses: A global challenge illustrated by Chikungunya virus outbreaks. World J Virol. 2012 Feb 12;1(1):11–22.

- Reiskind MH, Pesko K, Westbrook CJ, et al. Susceptibility of Florida mosquitoes to infection with chikungunya virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008 Mar;78(3):422–425.

- Reiter P, Fontenille D, Paupy C. Aedes albopictus as an epidemic vector of chikungunya virus: Another emerging problem? Lancet Infect Dis. 2006 Aug;6(8):463-464.

- Rochlin I, Ninivaggi DV, Hutchinson ML, et al. Climate change and range expansion of the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) in Northeastern USA: Implications for public health practitioners. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60874.

- Fourie ED, Morrison JG. Rheumatoid arthritic syndrome after chikungunya fever. S Afr Med J. 1979 Jul 28;56(4):130–132.

- Lynch N, Ellis Pegler R. Persistent arthritis following Chikungunya virus infection. N Z Med J. 2010 Oct 15;123(1324):79–81.

- Brighton SW. Chloroquine phosphate treatment of chronic Chikungunya arthritis. An open pilot study. S Afr Med J. 1984 Aug 11;66(6):217–218.

- Bouquillard E, Combe B. Rheumatoid arthritis after Chikungunya fever: A prospective follow-up study of 21 cases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Sep;68(9):1505–1506.

- Manimunda SP, Vijayachari P, Uppoor R, et al. Clinical progression of chikungunya fever during acute and chronic arthritic stages and the changes in joint morphology as revealed by imaging. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010 Jun;104(6):392–399.

- Chaaithanya IK, Muruganandam N, Raghuraj U, et al. Chronic inflammatory arthritis with persisting bony erosions in patients following chikungunya infection. Indian J Med Res. 2014 Jul;140(1):142–145.

- Queyriaux B, Simon F, Grandadam M, et al. Clinical burden of chikungunya virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008 Jan;8(1):2–3.

- Simon F, Javelle E, Oliver M, et al. Chikungunya virus infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011 Jun;13(3):218–228.

- Mohan A, Kiran DH, Manohar IC, et al. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of Chikungunya fever: Lessons learned from the re-emerging epidemic. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55(1):54–63.

- Gerardin P, Barau G, Michault A, et al. Multidisciplinary prospective study of mother-to-child chikungunya virus infections on the island of La Réunion. PLoS Med. 2008 Mar 18;5(3):e60.

- Hoarau JJ, Jaffar Bandjee MC, Krejbich Trotot P, et al. Persistent chronic inflammation and infection by Chikungunya arthritogenic alphavirus in spite of a robust host immune response. J Immunol. 2010 May 15;184(10):5914–5927.

- de Lamballerie X, Ninove L, Charrel RN. Antiviral treatment of chikungunya virus infection. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009 Apr;9(2):101–104.

- Labadie K, Larcher T, Joubert C, et al. Chikungunya disease in nonhuman primates involves long-term viral persistence in macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2010 Mar;120(3):894–906.

- Chopra A, Saluja M, Venugopalan A. Effectiveness of chloroquine and inflammatory cytokine response in patients with early persistent musculoskeletal pain and arthritis following chikungunya virus infection. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Feb;66(2):319–326.