Although pediatric rheumatologists care for disease entities distinct from those seen by adult rheumatologists, childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) and adult-onset SLE (aSLE) are fundamentally the same disease along a continuum. Important differences exist in disease manifestations, severity, and management that require consideration of the unique issues of the child and adolescent with chronic disease. SLE in childhood or adolescence accounts for 15% to 20% of all cases of SLE, with an approximate prevalence just below 1 per 10,000 children in the U.S.

The ACR classification criteria for SLE are used to classify patients with cSLE much as they are for aSLE, with one validation study demonstrating 96% sensitivity and 100% specificity in cSLE.1 The recently published Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) classification criteria appear useful for cSLE, although they await systematic evaluation.2

Disease Characteristics

The distribution of cSLE is skewed towards non-Caucasian ethnicities. Recent analysis of the prevalence of SLE and lupus nephritis (LN) among children in the U.S. Medicaid beneficiary population noted the greatest incidence of disease in Asian, African-American, Native American, and Hispanic children.3 Further, LN had the highest prevalence in Asian children, and lowest in white children, though there are possible biases when analyzing this database.3

Among the cohort in Canada’s “1,000 Faces of Lupus” study—which included almost 1,700 aSLE and cSLE patients—48% of all Asian patients had childhood onset, compared with only 14% of white patients with SLE. In addition to greater prevalence in nonwhite ethnicities, my colleagues and I have observed greater disease severity in these patient groups. Analysis of patients with cSLE in the Canadian cohort found that Aboriginal Canadians, Asians, and blacks more frequently developed moderate-to-severe disease (with LN and significant cytopenias), while white patients experienced mild or moderate disease (with predominantly mucocutaneous features and arthritis).4

More than ethnicity, genotype likely influences age of onset, ultimate disease burden, and phenotype. Large, genetic cohort studies comparing cSLE and aSLE are underway that may help to elucidate some of these differences. In Canada, disease severity may be less impacted by access-to-care issues because there is a nationwide program of universal healthcare coverage.

Disease activity at presentation and during the disease course is greater for cSLE compared with aSLE. For example, one study observed mean SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) scores at diagnosis of 16.8 ± 10.1 in cSLE versus 9.3 ± 7.6 in aSLE (P<0.0001).5 Not surprisingly, greater disease activity leads to more significant and earlier damage (such as cataracts, avascular necrosis, or persistent cognitive dysfunction) in cSLE.

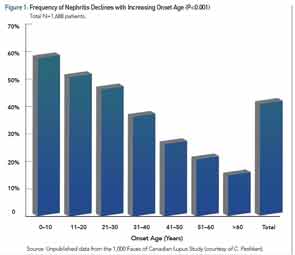

Among the larger published cSLE cohorts, the average age of diagnosis is 12.5 years, so cSLE is not only a disease that affects adolescents, as many children present in the first decade of life. Recent literature reviews and a meta-analysis have examined the clinical similarities and differences between cSLE and aSLE.6-8 All agree that malar rash, lymphadenopathy, cytopenias, and nephritis have a greater prevalence in cSLE. Figure 1 illustrates the decreasing incidence of renal disease with increasing age of SLE diagnosis.

Neuropsychiatric SLE (NPSLE), as defined by the 1999 ACR case definitions, is less clear. A recent study of our Toronto-based cSLE cohort found that 12% of 447 patients developed psychosis and/or significant cognitive dysfunction, and one-third of these patients reported suicidal ideation.9 Other recent studies suggest that psychosis is likely more prevalent, if not at least as prevalent in cSLE as it is in aSLE. The occurrence of seizures is less clear, as their attribution may be multifactorial: NPSLE, a complication of nephritis and significant hypertension, an adverse event from a drug, or complication of the macrophage activation syndrome. Headaches are frequent in cSLE, and the prevalence probably does not differ from aSLE.

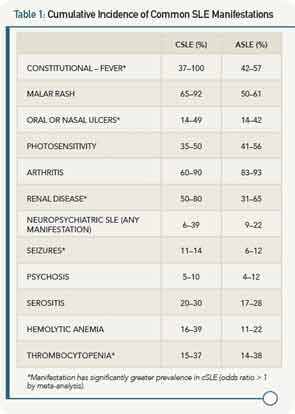

Autoantibody profiles are similar between cSLE and aSLE, except for anticardiolipin antibodies, which may be more common in cSLE. Table 1 provides a comparison of the most common disease manifestations, as reported in the past 10 years, between cSLE and aSLE.

With an understanding of cSLE manifestations, the following is a typical case that highlights some common management issues.

Case

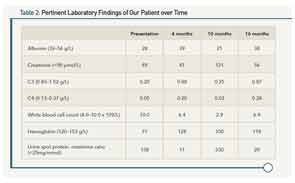

A 14-year-old, African-Canadian female presents with malar rash, alopecia, polyarthritis, hypertension, nephrotic-range proteinuria, peripheral edema, and a moderate-sized pericardial effusion. At presentation, laboratory values are notable for hypoalbuminemia, hypocomplementemia, and lymphopenia, along with the presence of a positive test for antinuclear antibodies, double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith antibodies, and anti-ribonucleoprotein antibodies (see Table 2). A renal biopsy demonstrates proliferative glomerulonephritis (ISN Class III). Oral prednisone (20 mg po TID) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF, 1,000 mg BID) were prescribed. After six weeks, her prednisone was tapered to 50 mg daily. By four months, the prednisone dose was reduced to 30 mg daily. She had minimal proteinuria, the serum complements normalized, and her blood pressure was <75th percentile for her age and height. Other clinical features (rash, arthritis, and serositis) were absent. The dose of prednisone was tapered further, but she does not return to clinic for almost five months (10 months following diagnosis).

Upon return, she is found to be in acute kidney injury, with peripheral edema, hypertension, and abnormal laboratory parameters as noted in Table 1. She admits that she has not been adherent to her drug regimen and states she felt “well” until just this past week. In the interim, she lost her supplemental drug coverage that paid for her MMF. Prednisone was reinstituted along with IV cyclophosphamide using the EuroLupus dosing regimen. She demonstrated a slow and consistent improvement, and laboratory parameters six months following reinstitution of therapy continued towards normalization. Current medications include hydroxychloroquine, a slow prednisone taper schedule, and mycophenolate sodium following re-induction. She has recently become sexually active, and states that she “sometimes” forgets her medications. She attends school “most days,” but is not happy with her appearance, and has difficulty concentrating and remembering what she is learning in school.

Management

There are several unique issues to consider in the management of cSLE. While the principles of drug therapy are similar to aSLE, the treatment of the child/adolescent requires greater involvement of the physician and other healthcare providers. In addition to the usual issues in caring for adults with SLE, the treating team must be mindful of normal expected growth and development, pubertal status, age and stage of adolescence, maturity, self-management capacity, and education and involvement of the family. The usual adolescent issues are magnified by the addition of a chronic disease, while fatigue, joint pain, and “lupus fog” make school and extracurricular participation difficult. Medication adherence is a significant challenge, and side effects have a significant impact on the ability and confidence of the adolescent to establish new friendships and intimate relationships that are crucial during this period. The “sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll” phase of adolescence (i.e., periods of normal experimentation) is altered by the disease and its treatment, which can contribute to both abnormal socialization and mood disorders.

Medication choices in cSLE are derived or extrapolated from aSLE clinical trials, with modifications made based on observational data and the severity of organ involvement. Drug dosing is based on pharmacokinetic considerations including age, weight, and body surface area. Recent studies suggest more than 90% of patients with cSLE require prednisone at some point in their disease course, despite the fact that its side effects including weight gain, acne, cushingoid facies, striae, increased facial hair, and mood alterations may be devastating to the adolescent and child alike.4,10 Antimalarial drugs are prescribed almost universally to patients with cSLE. Immunosuppressants, including methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide, and MMF, are prescribed for patients with organ involvement and for those who are unable to successfully taper off prednisone. The Aspreva Lupus Management Study (ALMS) compared MMF versus cyclophosphamide for LN. It was the first clinical trial for LN to include cSLE patients over 12 years old. Examination of the study’s 24 cSLE subjects in the ALMS study suggested no difference in response rate between the drugs for induction of LN, but the study lacked adequate power for this subgroup analysis.11

This dearth of trial-based evidence has led to the development of consensus treatment plans (CTPs) for cSLE and other pediatric rheumatologic diseases. These CTPs have been created through recognized consensus methodology by the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA), and for cSLE, provide the physician with a choice of treatment plans for induction and maintenance of proliferative LN.12 Data will be collected from multiple centers using the CTPs for comparative effectiveness research, and in this case, a comparison of MMF versus IV cyclophosphamide with concomitant oral and/or IV corticosteroids. With the high cost of industry-sponsored, randomized controlled trials, using observational data collected in a rigorous prospective manner and analyzed with newer statistical methodologies are the most realistic and cost-effective ways for pediatric rheumatologists to address many of the treatment questions in this relatively rare disease.

Cyclophosphamide has traditionally played a pivotal role in the treatment of severe organ involvement and rare life-threatening complications such as pulmonary hemorrhage. At our center, we have rarely used this drug for induction treatment for LN and instead have reserved its use primarily for patients with severe NPSLE—psychosis, acute confusional state, what was called “lupus cerebritis” or “organic brain syndrome”—and for severe cognitive dysfunction occurring concomitantly with other NPSLE syndromes. Our practice change to cyclophosphamide for NPSLE treatment occurred as more than 50% of patients initially treated with azathioprine (and corticosteroids) required escalation of therapy due to inadequate response.13

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval of belimumab as “the first new drug for SLE in 50 years” was lauded within the SLE community. However, the drug is indicated for adults with SLE, and as is frequently the case, pediatric rheumatologists are limited to “off-label” prescribing. In Canada as in the U.S., there are many payers who will not cover biologic drugs for off-label therapy. Thus, we await results from the ongoing international randomized controlled trial (RCT) of this drug in cSLE. Although rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, may be effective in the treatment armamentarium of cSLE, following the disappointing results of the aSLE rituximab trials, no phase III or IV study has been conducted in cSLE. Anecdotally, the pediatric rheumatology community uses rituximab for treatment-resistant cSLE manifestations including refractory CNS disease, renal disease, and cytopenias. At the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, 24 patients with cytopenias have received 31 courses of rituximab, with achievement of a rapid and complete response in 23 patients over the past 10 years. This is a selected group of cSLE patients with cytopenias refractory to high-dose systemic corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, antimalarial drugs, and other immunosuppressants. Clinical response is durable at a median of two years of follow-up, and those patients who flared all responded to repeat courses of rituximab.

Back to the Case

Pediatric rheumatologists recognize that in order to achieve adequate disease control and autonomy, the adolescent with cSLE requires self-management skills, education, motivation, and engagement. Understanding adolescents’ relationships with their peers and parents, as well as their educational and extra-curricular involvement is crucial for successful disease management. The disease course outlined here is not infrequent, and requires a multidisciplinary team approach to promote adherence, to place the disease in the larger context of life, and to provide solutions to significant issues such as acne and depression. We are fortunate to have developed a successful multidisciplinary cSLE clinic, whereby all adolescents are regularly seen and reviewed by rheumatologists and nephrologists, members of the adolescent health team (physicians and nurse practitioners), and as required by psychiatrists, social workers, and nutritionists. When necessary, patients can access other specialists from dermatology, ophthalmology, and other fields. By combining multiple services and appointments into one day, adolescents are more likely to receive the care they require. Our transition program brings the adult rheumatologist to meet the transitioning adolescent at the pediatric hospital during their last appointment, with the completion of a health passport and wallet card with pertinent personalized disease information.

The next step in self-management is completion of a mobile app, which my colleagues and I have developed through consensus methodology and is currently being evaluated by a demographically diverse group of adolescents with cSLE at two sites (Toronto and Charleston, S.C.). The app aims to fulfill an unmet need, which is the ability to carry secure, personalized health information that can be made readily available in an emergency. It allows the user to set alarms and personalized reminders for medications and appointments; to log symptoms using text, menus, and diagrams; and integrate photos taken by the patient. Didactic information about SLE is available as are links to useful websites and videos. A portal to a secure social networking site for app users is being developed.

As is frequently the case in pediatric chronic disease, we do not know a great deal about the long-term outcomes of our patients. In general, patients with cSLE are transitioned to adult care between the ages of 18 and 21. Self-management of a chronic disease in young adulthood ranges from poor to excellent, and plays a big role in their ultimate health. The risks of adverse cardiovascular events are very high in young women with aSLE, and we can only assume at this point that disease onset in childhood leads to an even greater long-term risk due to multiple factors, in particular, the chronic inflammatory state.

Utilizing multiple health administrative databases, we have assembled and linked a cohort of 620 patients with cSLE diagnosed in Ontario over the past 30 years. We are examining long-term outcomes including rates of hospitalizations, renal failure, joint replacements (for avascular necrosis), pregnancy outcomes, and mortality. Early results suggest higher rates of serious cardiac events (angina, myocardial infarction, and stroke) than we would have expected in these predominantly young women (currently aged 30 to 45 years), with more definitive results available by the end of this year.

Since early mortality from cSLE is low, and management of major organ involvement is possible with newer and less toxic drugs and drug regimens, we need to focus on improving patients’ long-term outcomes. Several factors are at play, including: 1) successful transition of the adolescent to an independent young adult able to manage their disease in partnership with their adult care provider(s); 2) educational and employment opportunities; and 3) access to medical care with adequate insurance coverage, which is frequently tied to employment. Ongoing collaborative research will help provide the necessary tools to these adolescents and young adults, while continued drug discovery and inclusion of cSLE patients in clinical trials will hopefully improve outcomes and lessen disease burden and permanent damage from this chronic disease.

Dr. Levy is a pediatric rheumatologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

References

- Ferraz MB, Goldenberg J, Hilario MO, et al. Evaluation of the 1982 ARA lupus criteria data set in pediatric patients. Committees of Pediatric Rheumatology of the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics and the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1994;12:83-87.

- Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677-2686.

- Hiraki LT, Feldman CH, Liu J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and demographics of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis from 2000 to 2004 among children in the U.S. Medicaid beneficiary population. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64: 2669-2676.

- Levy DM, Peschken CA, Tucker LB, et al. Influence of ethnicity on childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: Results from a multiethnic multicenter Canadian cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:152-160.

- Brunner HI, Gladman DD, Ibañez D, Urowitz MD, Silverman ED. Difference in disease features between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:556-562.

- Livingston B, Bonner A, Pope J. Differences in clinical manifestations between childhood-onset lupus and adult-onset lupus: A meta-analysis. Lupus. 2011;20:1345-1355.

- Mina R, Brunner HI. Update on differences between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:218.

- Papadimitraki ED, Isenberg DA. Childhood- and adult-onset lupus: An update of similarities and differences. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2009;5:391-403.

- Lim LS, Lefebvre A, Benseler S, Peralta M, Silverman ED. Psychiatric illness of systemic lupus erythematosus in childhood: Spectrum of clinically important manifestations. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:506-512.

- Watson L, Leone V, Pilkington C, et al. Disease activity, severity, and damage in the UK Juvenile-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2356-2365.

- Sundel R, Solomons N, Lisk L, Aspreva Lupus Management Study (ALMS) Group. Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in adolescent patients with lupus nephritis: Evidence from a two-phase, prospective randomized trial. Lupus. 2012;21:1433-1443.

- Mina R, von Scheven E, Ardoin SP, et al. Consensus treatment plans for induction therapy of newly diagnosed proliferative lupus nephritis in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:375-383.

- Lim LS, Lefebvre A, Benseler S, Silverman ED. Longterm outcomes and damage accrual in patients with childhood systemic lupus erythematosus with psychosis and severe cognitive dysfunction. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:513-519.