Looking for cutting edge clinical information? Here are some treatment advance updates from the ACR State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium. See the June issue here.

Strides in Diagnosing, Treating Sjögren’s

“One interesting change is the prevalence of Sjögren’s,” said Frederick B. Vivino, MD, a rheumatologist at Penn Rheumatology Associates and the Sjögren’s Syndrome Center in Philadelphia. “Many experts consider it to be the second most common autoimmune rheumatic disease.” In his presentation, “Sjögren’s Syndrome: Comprehensive Diagnosis and Management,” he stressed that, “just like in lupus, you’re dealing with an entire spectrum of disease.” Dr. Vivino reviewed diagnosis of Sjögren’s, including unusual presentations of symptoms like inflammatory myositis, fever of unknown origin, chronic fatigue syndrome, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

“Sicca symptoms may be minimal or nil,” warned Dr. Vivino. There may be a discrepancy between symptoms and results of objective tests of eye and mouth dryness. “The bottom line is that if you have a patient with symptoms that fit, you’re obligated to order tests for Sjögren’s.”

He stressed using the American-European criteria for earlier and better diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome. “These criteria are in use in nearly every children’s center in the world,” said Dr. Vivino. “They clearly represent an advance over what we had before.”

The criteria call for four of the following six symptoms to be present for diagnosis:

Subjective

- Dry eye symptoms; and

- Dry mouth symptoms.

Objective

- Abnormal test for dry eyes;

- Abnormal test for dry mouth;

- Positive anti-SSA/SSB*; or

- Positive lip biopsy.*

*Required

“One of the four objective criteria must be proof of the presence of autoantibodies,” Dr. Vivino pointed out. “This clearly represents an advance over what we had before.”

Errors are often made in reading salivary gland biopsies; a previous study by Dr. Vivino found that 53% of 60 accessions had errors. Other problems include lack of focus score, misinterpretation of focus score, and failure to examine all sections. “It behooves us to talk to our pathologists about accurate test results,” he said.

He pointed out that Sjögren’s can lead to a lot of disease complications, specifically lymphoma. “Lymphomas are the most important cause of morbidity and mortality in Sjögren’s syndrome patients,” said Dr. Vivino. “This is confusing, but the best predictors of lymphomagenesis include persistent parotid enlargement, persistent lymphadenopathy, palpable purpura, mixed monoclonal cryoglubulinemia, and low complement of C4.”

As for symptoms, there has been recent progress in treating dry eyes. This symptom has greatest quality-of-life effect. Research has shown that inflammation is tied to dry-eye disease. New evidence points to secretagogues, such as pilocarpine and cevimeline, that can alleviate symptoms. Fatty acids seem to play a role as well.

Dr. Vivino ended by discussing appropriate treatment for Sjögren’s, recommending immunosuppressives, such as hydroxychloroquine, or corticosteroids, but warned that these don’t have proven benefit for dry mouth or dry eyes.

Hear the Sessions

These and other sessions from the ACR State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium are available as audio CDs, MP3s, and podcasts. Visit www.ACRMeetings.com to view the sessions currently available from the meeting.

Distinguish Myopathy from Mimics

In “Myositis: From Autoantibodies to Clinical Trial,” Chester V. Oddis, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, provided guidelines for diagnosing and treating myositis syndromes.

Dr. Oddis began by reviewing the diagnostic criteria for idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, which include:

- Symmetric proximal muscle weakness;

- Elevation of serum muscle enzymes (creatine kinase, aldolase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, or anti-diuretic hormone);

- Myopathic electromyographic abnormalities;

- Characteristic muscle pathology; and

- Skin rash of dermatomyositis.

He then discussed several mimics of inflammatory myositis, including endocrine myopathies of hyper- and hypothyroid, metabolic myopathies, muscular dystrophies, and (the most common) drug or toxic myopathies caused by alcohol, colchicines, statins, and more.

“We all struggle with statins and statin myopathy,” said Dr. Oddis. Factors that increase risk of statin myopathy include increasing age, female gender, renal insufficiency, hepatic dysfunction, hypothyroidism, diet, and polypharmacy.

Dr. Oddis recommended a muscle biopsy to distinguish myopathy from immune-mediated myositis, or polymyositis, that’s amenable to treatment with steroids.

“In a patient with refractory polymyositis, consider the mimics of inflammatory myopathy,” he advised, “and you also have to consider inclusion body myositis [IBM].” Although it’s the most common myopathy, this is often missed. IBM is more prevalent in elderly males and includes an insidious onset of painless muscle weakness with slow progression. There’s a characteristic pattern of muscle atrophy in forearm flexors, quadriceps, and intrinsic muscles of the hands.

Although dermatomyositis (DM) may appear to be polymyositis with a rash, “it’s much more complicated than this,” explained Dr. Oddis. In polymyositis, the target is myofiber; in dermatomyositis, the target is blood vessels—treatment for the two must be different.

In a classic DM model, the autoimmune disease is mediated by an adaptive immune system and you’ll find a locally humorally mediated response with B and T helper cell infiltration. You’ll also find perifascicular atrophy of muscle fibers caused by ischemia. But investigations over the last few years have found specific gene transcriptional patterns in DM muscle tissues, including genes identified as type 1 interferon-induced. This is similar to a genetic signature found in lupus.

Dr. Oddis reviewed the two classifications of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: clinical groups, including adult and juvenile, and serologic groups, or those with autoantibodies. The second group includes myositis-specific autoantibodies. Categories of myositis-specific autoantibodies include anti-synthetases, which present with acute and aggressive onset with pulmonary symptoms such as interstitial lung disease. Other symptoms include high fever, inflammatory arthritis, and sometimes deforming arthritis of the hands. These patients are often thought to have pneumonia and/or rheumatoid arthritis, said Dr. Oddis. The pulmonary involvement can be life threatening.

There is very little evidence-based treatment for pharmacologic therapy of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, according to Dr. Oddis. Current treatment may include corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, combination regiments, intravenous immunoglobulin, and biologic agents such as anti-TNF agents, monoclonal anti-B cell agents, and monoclonal anti-complement agents.

A current NIH trial is assessing the efficacy of rituximab in polymyositis and DM, said Dr. Oddis.

Childhood Vasculitis Update

Rayfel Schneider, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto in Ontario and head of rheumatology at the Hospital for Sick Children there, presented “Pediatric Vasculitis,” a review of the current classification of childhood vasculitis, diagnostic pitfalls, and new treatment developments.

Beginning with the 2005 practical classification for childhood vasculitis—which Dr. Schneider calls “a work in progress”—he reviewed large-vessel, medium size–vessel, and small-vessel vasculities. He then focused on Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG)—a small-vessel vasculitis—and primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) in children, because, he says, “we’re seeing an increasing number of patients with isolated vasculitis of the CNS and we’ve done some work in that area.”

Dr. Schneider outlined recent research on Wegener’s granulomatosis in children, pointing out common symptoms including fever, arthralgia, and weight loss; glomerulonephritis; upper airway disease; and pulmonary disease. Less common symptoms include eye involvement, skin vasculitis, arthritis, and venous thrombosis.

“Wegener’s in children is more common in females,” Dr. Schneider says. “Think about Wegener’s in children with ‘atypical’ [Henoch-Schoenlein purpura]. Constitutional symptoms and upper airway, pulmonary, and renal involvement are all very common at presentation, and some patients may present with [deep venous thrombosis].”

Dr. Schneider then reviewed the proposed diagnostic criteria for PACNS, which include newly acquired neurological deficit, angiographic and/or histological features of CNS vasculitis, and no evidence of a systemic condition associated with these findings. Mimics must also be excluded.

He stressed that PACNS is a heterogeneous disease. It can present with acute stroke or diffuse neurological deficits—or with both. Permanent neurological deficits are frequent.

All diagnostic modalities have limitations, Dr. Schneider pointed out. “Lab and CSF tests aren’t sensitive or specific—the same is true of MRIs—and angiography is frequently positive and lacks sensitivity for small vessel disease.” The solution: Brain and leptomeningeal biopsies should be used in cases of children with suspected PACNS who have negative angiography. Additionally, identifying patients at high risk of progression may help determine whether they’ll require immunosuppressive therapy.

At the Hospital for Sick Children, four patients with biopsy-proven small vessel vasculitis were treated as follows. All four were given prednisone, two were given cyclophosphamide, and one was given azathioprine. Three of the four recovered with no neurological deficit, and there was a relapse in one patient recently, six years after treatment.

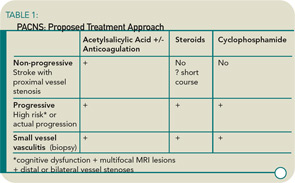

Dr. Schneider’s research shows that the patients with angiographic PACNS most likely to get progressive disease had three indications: neurocognitive dysfunction; multifocal, bilateral MR lesions; and distal stenoses on angiogram. This led him to think that the classification for vasculitis should be re-examined and should include the following categories: progressive, non-progressive, and small vessel (biopsy), each with a separate treatment. (See Table 1)

Jane Jerrard is a journalist based in Chicago.