The first clinical practice guidelines for Sjögren’s syndrome have been released, the culmination of an initiative by the Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation.1 These standard-of-care recommendations are intended to provide consistency in practice patterns, inform coverage and reimbursement policies, lead to the design and implementation of educational programs, highlight the needs for future research and fill a significant clinical void, according to the document published in Arthritis Care & Research, April 2017.

The Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation effort was led by CEO Steven Taylor and Vice President for Research Katherine Moreland Hammitt. The guidelines represent the first phase of treatment guidelines for Sjögren’s syndrome and address the use of biologic agents, management of fatigue and inflammatory musculoskeletal pain. The first phase was chaired by Fredrick B. Vivino, MD, at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, University of Pennsylvania. The next set of guidelines, which will be developed over the next couple of years, will look at several more of the 10 issues considered most important by the guidelines committee.

Lead author Steven E. Carsons, MD, at NYU Winthrop Hospital Campus and professor of medicine at Stony Brook University School of Medicine, says the clinical practice guidelines “will be extremely valuable for clinicians who treat Sjögren’s and for payers as a guide to appropriate management strategies. These are the first formally constructed guidelines for Sjögren’s syndrome intended for U.S. practitioners, … and they provide some clarity toward a preferred approach to the management of the manifestations of Sjögren’s.”

The Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation, founded about 35 years ago, was the first organization to raise awareness about the disorder, Dr. Carsons says. “On the basis of [its] efforts and efforts by others in Europe and elsewhere, there is now an awareness of Sjögren’s among patients and physicians.” This awareness has fostered a marked increase in research. “The culmination of all this interest and the environment of advances in so many other fields in rheumatology led to questions about what we can do about Sjögren’s, an area where we have not had a lot of good therapies and direction.”

In recent years, there has been a “fairly significant uptick in the number of agents being developed for Sjögren’s, and quite a few clinical trials in the U.S., Europe and other countries are now enrolling [patients]. That is in stark contrast to even five years ago,” Dr. Carsons says. Also, earlier this year, the ACR and EULAR released classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome, intended to improve the comparison of results across clinical studies and to aid in recruitment of patients for trials.2

Guidelines Development

The Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee employed a systematic review of the literature to inform a consensus expert panel (CEP), Dr. Carsons says. Recommendations were formulated by the experts according to the available literature and extrapolation from management of similar circumstances in other rheumatic diseases. The CEP, comprising rheumatologists, dentists, ophthalmologists, nurses, patients and allied health professionals, used Delphi methodology to achieve a 75% or greater consensus among the 30–40 participants for each of the recommendations.

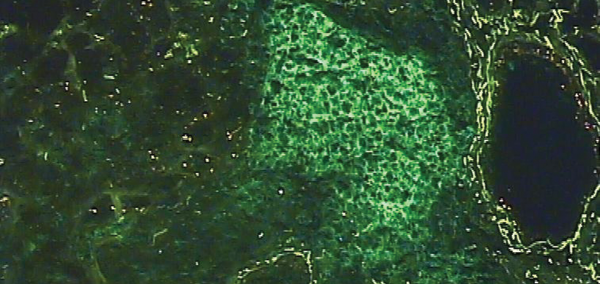

Photomicrograph of the salivary gland of a person with Sjögren’s syndrome, characterized by the abnormal migration of of lymphocytes T and B. Here only the lymphocytes B appear in green.

UEB IFR140 / ScienceSource.com

“We anticipate the guidelines will be used as an evidence- and expert-based reference to identify useful therapeutic pathways for highly relevant clinical questions,” Dr. Carsons says. “Due to the varied clinical presentation of Sjögren’s, we emphasize an individualized patient-centered approach.”

The committee endeavored to consider the context of rheumatology practice in formulating the guidelines to give practitioners “as many therapeutic options as possible while providing some guidance and clarity,” he says. “In other words, we really tried to not shut the door to therapies that some rheumatologists have found beneficial in their experience. On the other hand, the strength of our recommendations is strongly influenced by the quality of available evidence.”

Use of Biologic Therapies

The guidelines include a strong recommendation that tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors not be used to treat sicca symptoms in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. The recommendation was based on one small controlled trial and a multicenter randomized controlled trial. The committee recommends that patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome be monitored for toxicities if TNF inhibition therapy is being used for rheumatoid arthritis or other related and/or overlapping conditions.

The recommendation against TNF inhibitor therapy may be surprising, due to the comfort of rheumatologists with TNF inhibitors in multiple subtypes of autoimmune rheumatic diseases and a tendency to try them in related disorders when other therapies fail, Dr. Carsons explains. “However, because of the strength of the data from controlled trials in that area, we felt comfortable making that statement.”

Although TNF inhibitors are not recommended for treatment of glandular manifestations of Sjögren’s (xerophthalmia and xerostomia), their use is recommended should another rheumatic disease for which they are indicated be present, such as RA overlap or psoriasis, Dr. Carson says.

Another biologic agent, rituximab, may be considered a therapeutic option for keratoconjunctivitis sicca in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome, and it also may be considered for patients with xerostomia when there is evidence of residual salivary production and significant evidence of oral damage after conventional therapies have proved insufficient.

The guideline includes a strong recommendation that tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors not be used to treat sicca symptoms in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. … Their use is recommended should another rheumatic disease for which they are indicated be present, such as RA overlap or psoriasis. —Dr. Carson

“The decision to use a biologic agent, such as rituximab, to treat dry eyes and/or dry mouth would be appropriate only in severe cases and with necessary input from the patient’s ocular and/or oral medicine specialist,” the guidelines state.

Rituximab may also be a therapeutic option for adults with Sjögren’s syndrome who manifest any or all of the following: vasculitis, with or without cryoglobulinemia; severe parotid swelling; inflammatory arthritis; pulmonary disease; and peripheral neuropathy, especially mononeuritis multiplex.

“There probably is some discrepancy or dichotomy between what people may have gleaned from published conclusions of trials of rituximab for Sjögren’s and what the topic review group and the committee and consensus panel recommended,” Dr. Carsons says. “One has to dissect the data and examine secondary outcome measures and time points in order to come to an understanding that there may well be a benefit to the use of agents that target B cells in treating this disorder.

“Although no randomized clinical trial of rituximab in Sjögren’s syndrome has reached its primary endpoint to date, B cell depletion appears to show promise for both glandular and extraglandular manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome, including unresponsive inflammatory arthritis, as well as cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, interstitial lung disease and neuropathies, particularly mononeuritis multiplex,” he says.

Management of Fatigue

Fatigue is one of the most difficult management dilemmas in Sjögren’s syndrome, according to the authors, and the causes of fatigue are numerous. A comprehensive diagnostic evaluation should be conducted to exclude anemia, hypothyroidism, sedating medications and sleep disorders. Patients should be given advice about the value of exercise, which is the only strong recommendation for fatigue in patients with Sjögren’s.

The guideline indicates that hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) may be considered for treatment of fatigue in selected situations, such as presence of inflammatory markers, joint pain or rash. HCQ is the most widely prescribed treatment to manage fatigue in Sjögren’s in the U.S., but that practice is largely based on uncontrolled studies and clinical experience; thus, the recommendation was rated as weak and the overall quality of evidence was given a very low rating by the committee.

“Additional studies with different patient selection parameters, longer duration of therapy and alternate outcomes measures are needed before concluding that use of HCQ should be precluded in this setting,” according to the guidelines.

The guidelines do not recommend the use of biologics, such as TNF inhibitors, rituximab or newer agents, or dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) for fatigue alone.

Musculoskeletal Pain

Recommendations related to the management of inflammatory joint and musculoskeletal pain are represented by a hierarchical decision tree or sequential approach to therapy. Recommendations for agents that have similar efficacy and safety profiles are grouped together so practitioners can choose treatments based on their own experience and the specific patient circumstances.

According to the guidelines, HCQ remains the first-line option for inflammatory musculoskeletal pain; however, other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), such as methotrexate, may be considered in certain situations, including more severe cases when the perceived benefits outweigh the risk of increased toxicity. These situations include:

- Patients who are HCQ responsive but must discontinue therapy due to toxicity or adverse effects;

- Patients who have inadequate response to HCQ;

- Patients with severe steroid-responsive musculoskeletal pain and persistent symptoms who need another DMARD for steroid-sparing effect; and for

- Patients with objective evidence of synovitis.

The decision tree also states that when HCQ or methotrexate alone or the two in combination are ineffective, ≤15 mg/day of corticosteroids for one month or shorter time frame may be considered. Corticosteroids may be used for more than one month to manage inflammatory musculoskeletal pain, “but efforts should be made to find a steroid-sparing agent as soon as possible.”

Dr. Carsons

According to Dr. Carsons, clinicians who treat Sjögren’s syndrome should also become familiar with the published oral and ocular guidelines because, although some patients display prominent rheumatologic manifestations, nearly all Sjögren’s patients have dry eyes and dry mouth, complicated by ongoing ocular and dental problems.3,4 The guideline committee feels that rheumatologists should be familiar with the basic principles of managing ocular and oral manifestations in order to guide overall patient management, Dr. Carsons says.

“Managing patients with Sjögren’s syndrome involves multiple specialties, not only for treatment but also for diagnosis. You have to have close cooperation among rheumatologists, ophthalmologists and dentists,” Dr. Carsons says.

Sjögren’s syndrome remains one of the most difficult autoimmune rheumatic disorders to manage, and to date, there are no curative or remittive agents. The guidelines state that “therapeutic goals remain symptom palliation, improved quality of life, prevention of damage and appropriate selection of patients for immunosuppressive therapy.”

Supplemental material published online with the current manuscript offers information and observations about future directions for research, including development of improved outcome measures for research studies, additional investigation of B cells as therapeutic targets for Sjögren’s and development of orally administered small molecule immunomodulators for Sjögren’s treatment.

Kathy Holliman, MEd, has been a medical writer and editor since 1997.

In Brief

Sjögren’s syndrome remains one of the most difficult autoimmune rheumatic disorders to manage, and to date, there are no curative or remittive agents. The clinical practice guidelines from the Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation are designed to improve quality and consistency of care in Sjögren’s syndrome by offering recommendations for management. Consensus was achieved for 19 recommendations.

Key recommendations include a decision tree for the use of oral disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for inflammatory musculoskeletal pain, use of self-care measures and advice regarding exercise to reduce fatigue, and the use of rituximab in selected clinical settings for oral and ocular dryness and for certain extraglandular manifestations, including vasculitis, severe parotid swelling, inflammatory arthritis, pulmonary disease and mononeuritis multiplex.

The use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for sicca symptoms and for the majority of clinical contexts in primary Sjögren’s syndrome is strongly discouraged.

References

- Carsons SE, Vivino FB, Parke A, et al. Treatment guidelines for rheumatologic manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome: Use of biologic agents, management of fatigue, and inflammatory musculoskeletal pain. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 Apr;69(4):517–527.

- Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R, et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;69(1):35–45.

- Zero DT, Brennan MT, Daniels TE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for oral management of Sjögren disease: Dental caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016 Apr;147(4):295–305.

- Foulks GN, Forstot SL, Donshik PC, et al. Clinical guidelines for management of dry eye associated with Sjögren’s disease. Ocul Surf. 2015 Apr;13(2):118–132.