In this installment of our Rheumatology Drugs at a Glance series, we discuss the management of gout and offer insights from expert clinicians who have achieved a level of distinction in the field of rheumatology.

In this installment of our Rheumatology Drugs at a Glance series, we discuss the management of gout and offer insights from expert clinicians who have achieved a level of distinction in the field of rheumatology.

INITIAL TREATMENT

Several different medications, including corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and colchicine, are appropriate first-line options for the treatment of acute gout (see Table 1, below).1

Oral glucocorticoids are used in many patients, especially for those who have contraindications to NSAIDs. Glucocorticoids should be avoided in patients who have suspected or concomitant infection, prior glucocorticoid intolerance or brittle diabetes. They should also be avoided for those in a postoperative period for whom glucocorticoids may increase the risk of impaired wound healing.

Patients with frequently recurrent gout flares may prefer NSAIDs or low-dose colchicine to avoid excessive total glucocorticoid dosing over time. NSAIDs are an alternative to glucocorticoids in younger patients (those under 60 years old) who lack renal, cardiovascular or active gastrointestinal disease. Patients who have established gout who present with a typical flare limited to one to two joints may be candidates for parenteral glucocorticoids.

If you’re considering a combination product for a patient, colchicine/ probenecid is off patent and can now be obtained at a lower cost in the U.S.

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY

Below, we discuss common errors, clinical pearls, new safety data from the Food & Drug Administration (FDA), and the role of biologic therapies in the management of gout with our three experts in the field.

Brian F. Mandell, MD, PhD, FACR, MACP, is chair of academic medicine and a senior staff physician in rheumatology and immunologic diseases at the Center for Vasculitis Care and Research of the Cleveland Clinic, Ohio. He is the editor in chief of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine and a professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University. Dr. Mandell has served on national education planning and writing committees for the ACR, the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American College of Physicians. Dr. Mandell has published more than a hundred articles, chapters and editorials in peer-reviewed publications and textbooks relating to clinical and basic aspects of medical science.

Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, is chief of rheumatology and a professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine, and a professor of medicine at Boston University School of Public Health. Her research focuses on gout and osteoarthritis. Dr. Neogi helped lead the process to update the ACR Gout Management Guideline. At the 2019 ACR/ARP Annual Meeting, she presented a draft of the new guideline and was a featured speaker on gout in the Review Course, as well as in a Meet-the-Professor session. In addition to clinical care, research and teaching, one of Dr. Neogi’s key roles is to mentor trainees and junior faculty. Her research and mentorship have been recognized with several awards.

Lawrence Edwards, MD, MACP, MACR, is a professor of medicine and vice chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of Florida. He is an internationally recognized expert in gout and hyperuricemia and is CEO of the Gout Education Society, a nonprofit, web-based platform for improving medical literacy regarding gout for patients and clinicians. Dr. Edwards has also been awarded master status by both the ACR and the American College of Physicians.

‘There is no evidence that allopurinol is detrimental to renal function.’ —Dr. Neogi

Q&A

TR: What are the most common mistakes you see in gout management?

Dr. Mandell: The most common mistakes that I see, broadly, relate to the lack of patient education. Patients do not understand and that’s on us … that this really is a chronic disease, and it can be managed by maintaining a low serum urate level for long enough to dissolve the uric acid deposits.

Patients think of the disease as flares, which are really just symptoms; the disease is having the uric acid depositions in and around joints. That, ultimately, links to management decision mistakes. Clinicians should insist on follow-up and ensure that serum urate is kept low enough to dissolve the deposits.

In a recent [study], Michael Doherty, MD, looked at the ‘usual care given by physicians’ [defined as gout being managed predominantly by primary care physicians where there may have been insufficient time to educate patients adequately] and compared it with that provided by dedicated nurse educators.2 [The nurse-led approach focused on time and education: taking the time to explain what gout is, to make sure explanations were individualized and easy to understand, to address illness perceptions and to involve patients in shared decision making.] The difference between the two groups was striking: The nurses did great with keeping serum urate down, which translated directly to a dramatic decrease in the number of flares patients had; and the physicians could have done a better job. Nursing-led care led to 95% effectiveness compared with 30% in the physician care group—a huge difference.

Dr. Neogi: Some of the most common mistakes that I see are:

- Starting allopurinol at 300 mg/day rather than starting at a lower dose and titrating up to the appropriate dose that allows the patient to achieve and maintain a serum urate level below 6 mg/dL. This implicitly requires that patients have their serum urate monitored routinely to enable appropriate dose titration to achieve the serum urate target;

- Starting urate-lowering therapy [e.g., allopurinol, febuxostat, probenecid, pegloticase] without concomitant prophylaxis [colchicine];

- Not providing patients with appropriate medications to manage gout flares at the first signs of the flare—in other words not employing a medications-in-pocket strategy, so the patient can treat the gout flare as soon as possible rather than waiting to be seen by a physician or have a prescription called in, which delays treatment initiation;

- Flare therapy being of either insufficient dosage or duration to fully bring the flare to its resolution;

- Lack of education: Patients are not educated sufficiently to understand that they should continue urate-lowering therapy during a flare; and

- When patients with gout have a rise in their creatinine, it is common practice for allopurinol to be held, particularly for patients who are hospitalized. However, it is more likely that other factors have contributed to the renal function decline than allopurinol; there is no evidence that allopurinol is detrimental to renal function.

Dr. Edwards: One of the most important and common mistakes that we make as clinicians is not taking the time to explain disease mechanisms and the utility of the medications we’re using. This is especially true with gout. The disease itself is easy enough to understand, and we use only a handful of drugs to either treat the inflammation of the disease or to lower serum uric acid levels. Taking the time early on in the patient’s disease process to cover these essential facts will greatly improve adherence and persistence in taking medications.

The second serious error is when clinicians don’t measure serum urate levels on a regular basis. During the initial dose and escalation of the urate-lowering therapy, serum urate levels should be obtained two to three weeks after each dose adjustment and prior to the next escalation. Once a patient has achieved the appropriate target serum urate level, serum urate levels should be monitored every six to 12 months to ensure adherence to, and effectiveness of, therapy.

The assumption that patients are going to be adequately treated if we can just get the allopurinol dose to 300 mg daily is simply false. In fact, less than 40% of gout patients will achieve a target a serum urate level of ≤6.0 mg/dL on 300 mg of allopurinol. The mean dose of allopurinol to achieve target is closer to 400 mg daily, and many patients will require up to 600 or even 800 mg daily. Continuing to monitor serum urate and escalating the urate-lowering therapy until the target is achieved are absolutely crucial for optimal gout management.

Lastly, I think most clinicians underestimate the impact of gout on their patient’s quality of life. In the early stages of gout, the symptoms are intermittent and may be totally resolved by the time the patient visits their doctor. I hear from primary care physicians who tell me all the time that these patients have other medical problems, such as hypertension, kidney disease or diabetes, that are more serious and they simply don’t have the time to devote to gout. This, of course, should not be an either/or scenario. Treating gout is neither complicated nor time consuming. If the clinician spends some time initially describing the disease and its treatment strategy, long-term management is generally quite simple.

TR: Can you share any pearls regarding the management of gout?

Dr. Mandell: The major pearl is that clinicians need to spend adequate time with the patient at the first clinic visit or when a treatment plan is outlined. This should be before starting or concurrently with starting treatment; take at least 20 minutes to explain to the patients why this is a chronic disease, how we can actually treat and manage it and that it takes time to get rid of all the urate deposits. Clinicians should dedicate time with their patients, and if possible relevant family members; then reinforce the information with patients at future visits—communicate with them directly at face-to-face visits, email follow-up messages and/or nurse practitioner visits.

The other pearl is simply to follow the serum urate and escalate the dose to treat to target to maintain the low urate level.

Like most physicians who have actual experience in treating patients with gout, I strongly disagree with the American College of Physicians’ recommendations on managing patients with gout. It’s been reported in a number of studies that physicians don’t escalate allopurinol (which is the most commonly prescribed urate-lowering therapy) sufficiently to get to the optimal serum urate. The lower the serum urate, the faster the deposits will disappear. But the lower the initial serum urate, the more likely it is that patients will have flares at the beginning. Hence, the target level should be individualized.

This requires patient education and an understanding that as we treat the disease―which is the deposition—and the serum urate gets lower, attacks [flares] can increase before they decrease. If this is not explained well to patients, they will assume the drug isn’t working. The fact is, however, that experiencing a flare early on is a sign the drug is working and the deposits are dissolving.

Adherence is rarely an issue in my gout patients because of patient education that is occurring in our clinic.

Dr. Neogi: The management of gout requires engagement in patient education so patients understand the various aspects of gout management necessary to bring their disease under control. Control includes understanding the foundation of managing hyperuricemia with urate-lowering therapy, use of prophylaxis during the early stages of urate-lowering therapy and appropriate management of gout flares.

I often engage in these conversations by using a bathtub analogy for explaining the level of urate in the body and how we can try to lower that level by turning off the tap (xanthine oxidase inhibitors), increasing the flow through the drain (uricosuric agents) or taking a bucket to remove the water (pegloticase).

Separately, we discuss management of gout flares as putting out a fire, which requires separate approaches to what we’re trying to do with the bathtub.

Ongoing engagement with patients and reinforcing their understanding can help with long-term adherence. Exploration of potential triggering factors and/or excessive dietary factors can be a helpful component to their overall gout management. However, lifestyle modification discussions should be engaged in a sensitive manner, because patient blaming/shaming can be a detriment to a patient’s willingness to discuss their gout and a detriment to the therapeutic alliance.

In addition to the important patient education piece, the basics of gout management include addressing those common mistakes listed above: starting urate-lowering therapy at a low dose and titrating up in a timely manner, which requires serum urate monitoring, to achieve the serum urate target; providing concomitant prophylaxis when starting urate-lowering therapy; and ensuring a sufficient duration of prophylaxis guided by stable urate levels below the target of 6 mg/dL and cessation of flares; and providing appropriate dose and duration of flare therapy to resolution.

Dr. Edwards: I spend very little time discussing the impact of diet on gout with my patients. Most patients already know if particular foods cause gouty flares, and they are already avoiding them. Eliminating these foods from the diet will not have a significant impact on the disease over time. Instead, I spend the time discussing the role of urate-lowering medications, which can, if appropriately used, eliminate the pain and joint destruction that accompanies gout.

The trick to treating gouty flares is to initiate anti-inflammatory therapy as early as possible. This generally means the patient should have a filled prescription of whatever medication they will use as an anti-inflammatory―be that colchicine, NSAIDs or corticosteroids. If the patient can start these medications in the first few hours of the flare, the episode can be greatly minimized. Physicians need to understand that allopurinol is not nephrotoxic. The correct dose of allopurinol in somebody with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is no different than the dose in somebody with normal renal function. That dose is whatever it takes to get the serum urate level to ≤6.0 mg/dL.

Allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS) is a rare (~1 in 1,000 drug starts) but potentially lethal complication of gout treatment. We can minimize the risk of this reaction by testing for HLA-B*5801 in Koreans with renal disease, Southeast Asians, Han Chinese and African American patients. There is also evidence that initiating allopurinol at a low dose (100 mg daily for most patients or 50 mg daily for patients with CKD stage 4–5) and slowly escalating to the effective treatment dose will lessen the risk of AHS.

TR: In light of recent data, what is the role of febuxostat (Uloric), and when is it preferred to allopurinol?

Dr. Mandell: My primary urate-lowering therapy is allopurinol, and the role of febuxostat hasn’t changed in my practice. The main reason for using febuxostat is if the patient has demonstrated intolerance to allopurinol because of gastrointestinal side effects or allergy. I also use allopurinol in patients with CKD, but if it’s not tolerated, I switch to febuxostat. It has never been a first-line drug because the cost of febuxostat is approximately 10 times that of allopurinol.

Despite the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study and FDA warning, I’m not convinced this will turn out to be a major issue. 3,4 There were significant problems with the conduct of that specific trial, including a large number of patient dropouts. There was a lack of biological consistency with the results; they are hard to understand physiologically, and there was an imbalance with patients taking aspirin as a cardio-protective drug between febuxostat and the allopurinol groups.

Other studies are being done, and there have been several published that have not shown similar results. Despite the many problems with the NEJM study, there is a black box warning, so I do discuss the cardiovascular risk with my patients if they need to go on the drug.

Dr. Neogi: The data regarding febuxostat with respect to cardiovascular risk has led to a recent FDA black box warning.4 There are a number of uncertainties with the interpretation of the CARES trial data that led to the FDA black box warning, particularly given the substantial treatment discontinuation and loss to follow-up, and that the majority of events occurred off treatment.3,4 Nonetheless, these data certainly reinforce the need for shared decision making, taking into account the unique circumstances for each patient and their preferences, highlighting that no single approach will be appropriate for all patients.

Allopurinol can be considered first-line therapy for virtually all patients with gout, even with renal insufficiency. A major issue is that most patients never have their allopurinol dose titrated above 300 mg/dL, whereas the majority of patients require a dose higher than 300 mg/dL to achieve the serum urate target <6 mg/dL and, therefore, have their clinical disease activity under control.

Studies have demonstrated that allopurinol can be safely dose escalated, even in those with renal insufficiency. Thus, only once allopurinol has failed to achieve the serum urate target for a given patient with appropriate dose titration or there are adverse events related to allopurinol (e.g., allergic reaction) should another agent be considered.

For patients with cardiovascular disease, a risk-benefit analysis of febuxostat use in the context of each patient’s individual profile should be evaluated, along with the lack of a definitive understanding of febuxostat risk vs. the risk of uncontrolled gout. This requires meaningful shared decision making with each patient.

Dr. Edwards: In 2018, the NEJM published the CARES trial that demonstrated in patients selected for high risk of cardiovascular disease that those receiving febuxostat were at increased risk for sudden cardiac death when compared with patients taking allopurinol.3 The cause of this risk is unknown, but this study did not demonstrate an increased incidence of other cardiovascular symptoms in patients receiving febuxostat. There was no placebo arm to the study, so we do not know if being on either allopurinol or febuxostat is more or less risky than being on neither xanthine oxidase inhibitor.

In Europe, the FAST trial has recently been completed, and we expect its publication within the year.5 This study also compared cardiovascular safety of allopurinol and febuxostat. We hope this study will shed more light on the true risk to our patients.

In the meantime, I think it’s prudent to consider allopurinol to be the first-line medication for urate lowering. If however, allopurinol is ineffective, not tolerated or is contraindicated, then febuxostat should be the next choice.

When I tell patients about the CARES trial, I say, “In a study of more than 6,000 patients who were at high risk for cardiovascular disease, 3% of patients on allopurinol and 4% of patients on febuxostat experienced sudden cardiac death over an average follow-up of 3.5 years.3 There are also multiple studies in the medical literature that say that being on any form of urate-lowering treatment decreases cardiovascular mortality.”

TR: What is the role of biologic therapies (i.e., anakinra [Kineret], pegloticase [Krystexxa]) in the management of gout?

Dr. Mandell: Anakinra is used to treat attacks, which is a symptom of the disease. I am a big fan of anakinra as a treatment for acute flares. I find it to be very well tolerated and very effective. It does not have the concerns with fluid balance, glucose or effects on the kidney that our other drugs have.

Other drugs that are used to treat acute attacks are the NSAIDs or prednisone or, sometimes, colchicine. I use colchicine more often for prophylaxis than to treat acute flares.

In the hospital setting, anakinra is often my drug of choice for acute flares because of the efficacy and safety profile―patients frequently have additional co-morbidities in the hospital. The problem with using it in the outpatient setting is cost. Anakinra is not FDA approved for treating gout, so in the outpatient setting, its use is off label, and insurance companies don’t generally cover the cost with using it in this setting.

However, anakinra is the most common drug we use on our consultation service for flares in the hospital; shortening the hospital stay easily recovers the cost of the drug.

Pegloticase is used to treat the disease as enzyme replacement therapy. Humans don’t have active uricase, so this provides the enzyme we’re missing to dramatically lower the serum urate to almost unmeasurable levels in patients who respond to the drug. But in clinical trials, that continued response was seen in only about 50% of patients. The problem is that patients make antibodies to the drug, and they neutralize it, so its efficacy disappears or decreases significantly. Those patients who have very high levels of antibodies who become resistant to the drug are also the ones who have infusion reactions. Although patients in clinical trials generally experienced mild infusion reactions, the reactions can potentially be problematic.

In practice now, if the patient is making antibodies to the drug, which then becomes less effective, the serum urate will start to increase, and we have to stop the infusions—usually using a serum urate of 6 mg/dL as a cutoff.

In clinical trials, about 50% of patients had to stop peglioticase; in my practice, 30–40% of patients have had to stop the drug. There was more benefit for those who could tolerate the therapy, but those patients who had to stop the drug still gained some benefit in dissolving the urate deposits in terms of overall joint discomfort and quality of life, as well as many reducing their tophus volume.

The value of peglioticase is that it lowers the serum urate so much that the deposits are dissolved fairly rapidly, often over the course of several months to less than a year. Patients who have so much tophus in their tendons and hands that they can’t even make a fist―those deposits will be dissolved, often over the course of months, in patients who are able to remain on the drug. The advantage of pegloticase is that it can dissolve deposits relatively quickly. However, not everybody who has tophi needs deposits dissolved very quickly.

Most patients who have a few tophi and few attacks are appropriate candidates for traditional therapy. Those patients whose function is dramatically limited by the amount of gouty deposits they have benefit if the deposits can be dissolved quickly. I have had patients with non-healing, infected tophi for whom I have used peglioticase and seen it dissolve the tophi, permit resolution of the infection and, essentially, save the patients from digit amputation.

Dr. Neogi: Many patients with gout have co-morbidities, intolerances and/or contraindications to the main options for managing gout flares, which include glucocorticoids, NSAIDs and colchicine. For such patients, an IL-1 antagonist, such as anakinra, provides an important and critical option in managing their gout flares. Patients with difficult-to-control tophaceous gout with ongoing clinical disease activity despite appropriate maximal dosing of oral urate-lowering therapy would benefit from pegloticase.

Interestingly, upon completion of pegloticase therapy, patients can often be transitioned back to oral therapy with success in maintaining control of clinical disease activity and serum urate levels below 6 mg/dL. This strategy can be considered as induction therapy to get the clinical disease activity related to gout under control (when oral therapies were not successful), followed by remission maintenance with oral urate-lowering therapy.

Dr. Edwards: I can still remember the words of a rheumatologist and a member of the Arthritis Advisory Panel to the FDA several years ago who said, “Gout does not deserve a biologic.” That is clearly not the case since both of these biologic agents have found very useful niches in the treatment of gout.

When pegloticase was first approved by the FDA nearly a decade ago, it was indicated for gout patients who had failed all other forms of urate-lowering treatments. In retrospect, that was an ill-advised approach because patients are not going to remain on pegloticase for their whole lives. After pegloticase has effectively melted away a good part of their urate burden, these patients will need to go on some other effective form of urate-lowering management for the rest of their lives.

We know from multiple studies that the lower we can get the serum urate level, the more rapidly stores of monosodium urate crystals will dissolve. In our standard approach of reducing serum urate to ≤6.0 mg/dL, the process of melting away clinical and subclinical tophi is frustratingly slow. Even the more aggressive approach of reducing the serum urate level to ≤5 or 4 mg/dL will only modestly improve the rate of dissolution. Dramatic reduction of gouty tophus mass can be accomplished in patients who respond well to pegloticase. I use this drug in patients with advanced gout in whom tophi are limiting physical function or reducing quality of life.

Anakinra has not been approved by the FDA for the treatment of gout flares, but IL-1 is the primary pro-inflammatory cytokine stirred up by crystal-induced NLRP-3 inflammasome activation. It makes sense that an IL-1 inhibitor, such as anakinra, would be effective. This has proved to be the case in multiple small studies and is frequently used in settings where acute gout flares are observed, such as the emergency department and in hospitalized patients.

CONCLUSION

Our physician experts, Dr. Mandell, Dr. Neogi and Dr. Edwards, acknowledge the challenges and limitations of the current management and treatment of gout. They provide a comprehensive discussion of the common errors, clinical pearls and safety issues associated with pharmacologic agents, and acknowledge the value of patient education and continuous patient monitoring. The updated ACR Gout Management Guideline was published in 2020.6

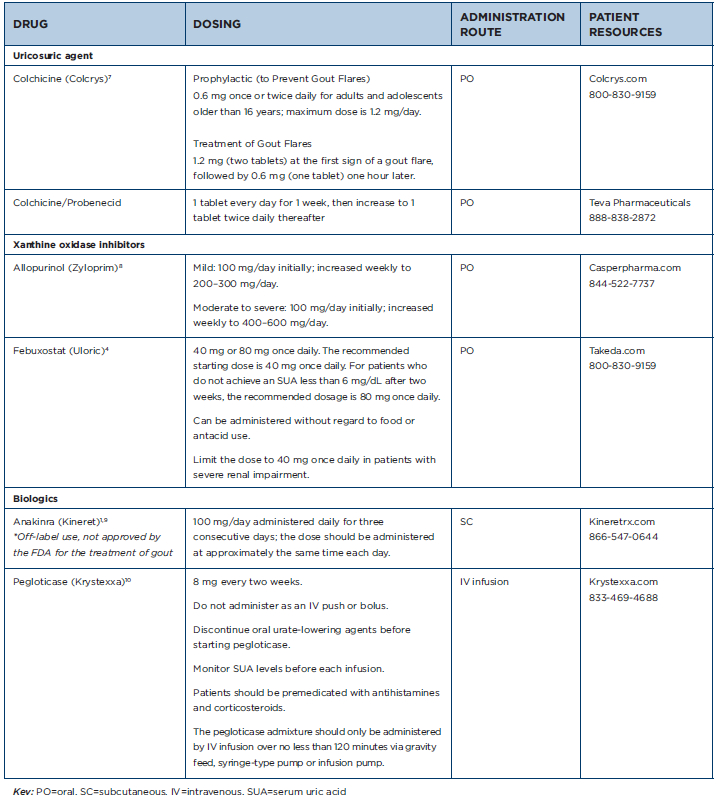

Table 1: Gout Medications at a Glance

Mary Choy, PharmD, BCGP, FASHP, is a medical writer and editor in New York City. Dr. Choy is director of pharmacy practice at the New York State Council of Health-system Pharmacists. She is also the author of Healthcare Heroes: The Medical Careers Guide.

References

- Khanna A, Khanna PP, FitzGerald JD, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology Guidelines for Management of Gout. Part 2: Therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Oct;64(10):1447–1461.

- Doherty M, Jenkins W, Richardson H, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018 Oct;20;392(10156):1403–1412.

- White WB, Saag KG, Becker MA, et al. Cardiovascular safety of febuxostat or allopurinol in patients with gout. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 29;378(13):1200–1210.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Uloric prescribing information. 2019 Feb. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/021856s013lbl.pdf.

- MacDonald TM, Ford I, Nuki G, et al. Protocol of the Febuxostat versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial (FAST): A large prospective, randomised, open, blinded endpoint study comparing the cardiovascular safety of allopurinol and febuxostat in the management of symptomatic hyperuricaemia. BMJ Open. 2014 Jul 10;4(7):e005354.

- American College of Rheumatology. 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken).

2020 June;72(6):744–760. - U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Colcrys prescribing information. 2015 Dec. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/022352s022lbl.pdf.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Zolprim prescribing information. 2018 Dec. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/016084s044lbl.pdf.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Kineret prescribing information. 2018 Jun. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/103950s5182lbl.pdf.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Krystexxa prescribing information. 2018 Jul. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125293s092lbl.pdf.

Editor’s note: First published November 2019; updated September 2020.

Rheumatology Drugs at a Glance

Previous installments in this series include:

- Part 1: Psoriatic Arthritis

- Part 2: Psoriasis

- Part 3: Rheumatoid Arthritis