Dr. Hwang

Dr. Hwang: The diagnosis of axSpA can be very challenging. I think that classification criteria are sometimes misused for diagnostic purposes instead of their more intended purpose of creating a relatively homogenous population for research. For our fellows-in-training, I try to frame classification criteria as part of the scaffold to build the clinical acumen/diagnostic skills off of instead of the definitive answer.

On the other hand, we also see some patients in our spondyloarthritis clinic who carry an axSpA diagnosis—I believe with very reasonable suspicion in that initial evaluation—that have different rheumatic and other health conditions that can explain their symptoms. I believe this is, in part, due to anchoring bias that we all struggle with due to the mutual respect we have in the rheumatology field for our colleagues. I think a constant reevaluation of the underlying diagnosis is important, especially when patients have had lacked continuity of care.

Dr. Liew: For non-rheumatologists, including primary care providers, it’s really an issue of education and understanding of what axSpA is.

Even the terminology itself is confusing. And, like other diseases in rheumatology, there are no diagnostic criteria. There are classification criteria, which are meant to be specific enough to get a homogenous population for a clinical trial or an observational cohort. However, this is not something that is widely understood, so classification criteria are often incorrectly used for diagnosis.

Then, if you have someone who is unaware of nr-axSpA or of the terminology, perhaps they look at the older, modified New York criteria for AS, which require clear structural changes in the sacroiliac joints on plain films. This will, of course, miss everyone who has, or might have, nr-axSpA.

All of this contributes to the very long diagnostic delay. There have been many studies about this, performed over two or so decades and in multiple countries. Steven Zhao in the U.K. performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of these studies; the pooled mean diagnostic delay was nearly seven years.2 In addition, these studies have also shown that the diagnostic delay has persisted despite advances in understanding of the disease, and this leads to a treatment delay. And a treatment delay may lead to lower response to treatment when it’s finally initiated.

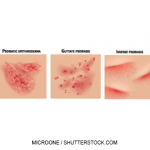

Again, it’s an education issue. But rheumatologists are not exempt from making mistakes with diagnosis and treatment in axSpA. And then you need to think: If it’s so difficult for us, how should we expect non-rheumatologists to get it right? There are people studying referral pathways to get patients with low back pain seen by rheumatologists sooner. For example, Fabian Proft in Germany published on the use of an online self-referral tool compared to a physician referral tool for chronic low back pain.3 In the U.S., a group at Yale is doing something similar with the Finding axSpA study (FaxSpA).4 Other groups are looking at improving referrals from ophthalmology, dermatology and gastroenterology clinics, for patients who have anterior uveitis, psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease.

Other common mistakes, in no particular order:

- Not considering the diagnosis of axSpA in women. We learn that axSpA is a male-predominant disease, with an illness script of a white man in his 20s with inflammatory back pain that responds to NSAIDs and exercise and worsens with rest. Although the illness script still works, we need to consider who we’re missing if we focus on that demographic. In nr-axSpA we don’t see this male predominance, unlike in axSpA.

- Misdiagnosis based on imaging. I’ve discussed the problem of missing nr-axSpA due to reliance on radiographs. There is also the other issue: overdiagnosis. As a field, we are working on better definitions for features on MRI that would be consistent with a diagnosis of nr-axSpA vs. features that are non-specific, or are non-specific if not present with other abnormalities. Studies of athletes and postpartum women have shown that bone marrow edema on MRI of the sacroiliac joints can be seen in people without axSpA.5,6

- Not starting TNF inhibitors sooner. Coupled with this, the reliance on methotrexate and sulfasalazine for peripheral disease but sometimes also axial disease (methotrexate is not recommended for either; sulfasalazine is only in the recommendations for peripheral involvement). AxSpA should not be treated like rheumatoid arthritis—they are very different diseases.

- Not emphasizing physical therapy and exercise (of any type). These are recommended for all patients with axSpA but physical therapy is very underutilized. Of course, not every patient has good access or the time or other means to attend regularly.

TR: What are some tips for the clinical management of axSpA?

Dr. Gensler:

a) Make sure the diagnosis is correct. If you are in the possible/probable zone, then set a time frame for response to treatment and don’t anchor to a diagnosis if treatment response is in the placebo range or less.

b) Consider using data to drive your decisions. Because the physical exam for axial involvement is limited in early disease and slowly responsive to treatment, the peripheral exam is not typically abnormal and the inflammatory markers are often normal (especially in women), consider measuring disease activity. I use a Bath Anklylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) as a point of care assessment and prefer an Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS-CRP) if the CRP is available. This gives me an outcome to look at over time that though subjective, compares to the patient’s own quantitative assessment from before. The ASDAS is almost always consistent with how the patient feels.

c) When patients come in complaining of increased pain or symptoms suggestive of disease activity, delve into both risks for uncontrolled disease (e.g., missed medications, changes in exercise, weight gain, stress, mental health) before switching to another medication. We have limited therapeutic options, so making sure the patient doesn’t have some other reversible reason for treatment failure is important. Additionally, if the reason for disease activity is not uncontrolled inflammation, then there is a risk of what I call the biologic spiral—switching from one drug to another without gaining disease control.

d) When sitting with a patient on a biologic with uncertain disease activity, consider using objective data to help drive decisions. Is the CRP elevated again? If not, do you need an MRI to identify bone marrow edema reflective of active disease, before changing?

e) Assess for extra-musculoskeletal manifestations as you consider treatment or treatment changes. I have a low threshold to evaluate for inflammatory bowel disease in axSpA.

Dr. Hwang: Structured exercise is very important. A balance of flexibility, postural, strength and aerobic exercises is important in the care of these patients. A trial of NSAIDs—as short as two to four weeks—can also be an alternative at times, before changing biologics, if patients have a partial response to biologic pharmacotherapy.