In Part 1 of this series, we covered the vital role of medical decision making in determining the final level to bill for a patient encounter. Medical decision making is the key component in coding because it reflects the intensity of the provider’s cognitive labor. This implies that there’s an unseen component involved in the Medicare Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management (E/M) Services that directly affects reimbursement for physician services. The guidelines clearly advise what a reviewer would look for to determine the level of decision making, but there’s not enough information for providers to plainly determine the level.

The process of medical decision making requires providers translate their internal clinical thoughts to paper for the care of a patient. This is where a provider’s thought process is quantified—and sometimes deemed the primary role in providing a summary documentation of a visit. Providers must confirm the medical record documentation supports the level of service reported to a payer and not necessarily use the volume of documentation to determine a specific level of service to bill. Services are to meet specific medical necessity requirements in the statute, regulations and manuals defined by National Coverage Determinations and Local Coverage Determinations (if any exist for the service reported).

The CMS defines medical necessity as, “healthcare services or supplies needed to prevent, diagnose or treat an illness, injury, condition, disease or its symptoms and that meet accepted standards of medicine.” In any of those circumstances, if a condition produces debilitating symptoms or side effects, then it is also considered medically necessary to treat those. The CMS continues, “No Medicare payment shall be made for items or services that are not reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member.”

In claim reviews, someone other than the provider is trying to confirm the level of decision making that is billed on a claim, but if auditing is involved, someone else is tasked with determining if the medical decision making meets the level of coding. Although EHRs have done a great job in managing a lot of information in patient notes, the following information is designed to assist providers with the tools to quantify the thoughts that are documented during a patient encounter.

Diagnoses & management options: Document the number of problems addressed during the visit that are relevant to the presenting problem. If there is a new problem, verify that this is clearly stated in the history of present illness, review of systems or examination. Showing how the patient condition is being handled is at the heart of disease management. The history and examination are not always enough to reach a diagnosis, so it is important to document what other work was done to arrive at a definitive diagnosis.

Data: The guidelines state there may be a need to look at “the amount and complexity of data to be reviewed.” This refers to information from sources other than the history and physical, lab tests, imaging, other diagnostic services, old records and history from sources other than the patient. This shows an increase in the complexity and volume of data you will need to review or order to help with the quality of care. Key factors to document for the data component include:

- the nature of any diagnostic service you order, plan, schedule or perform at the time of the encounter;

- any review of diagnostic test results that you perform;

- any decision to review old records or obtain history from sources other than the patient;

- relevant findings from any review of old records or from any additional history you obtain that will aid in verifying a diagnosis or in any treatment options;

- the results of any discussion you have with the physician who carried out or interpreted a diagnostic test or service; and

- “direct visualization and independent interpretation of an image, tracing or specimen” that has been or will be interpreted by another physician.

Such independent checking is not expected to be a regular thing, but rather something that rarely happens.

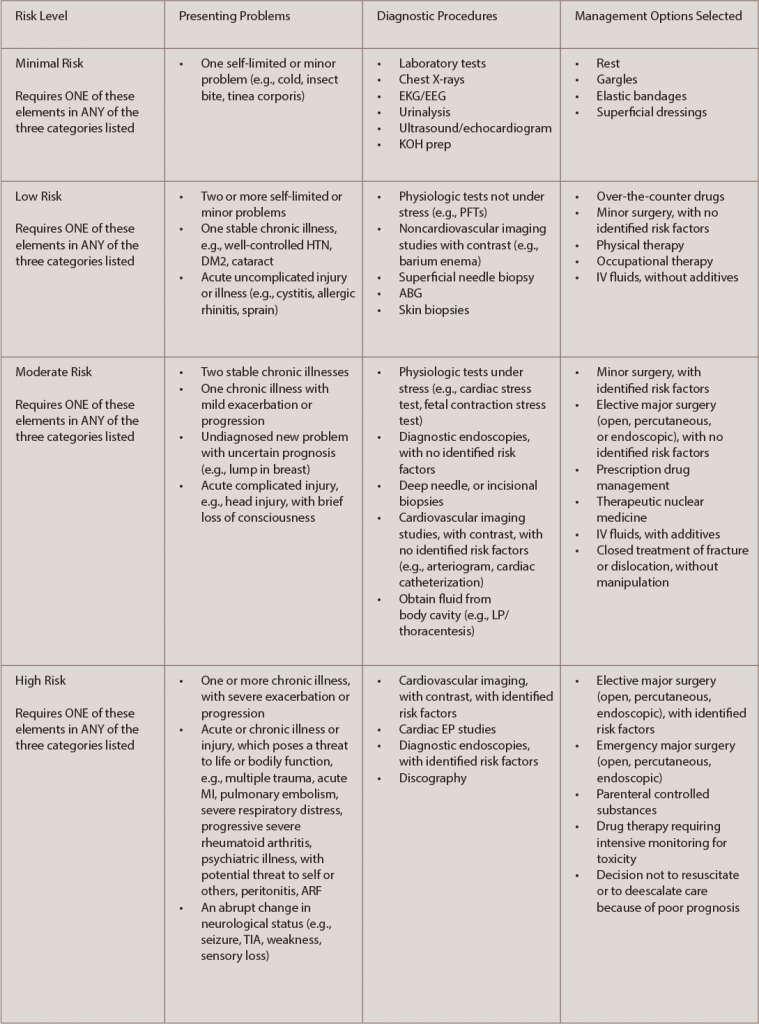

Risk: The guidelines consider risk to the patient in determining the level of medical decision making—risk of significant complications, morbidity and mortality—and they recognize three gauges of this risk: the presenting problems, any diagnostic procedures you choose and any management options you choose. Key documentation principles to follow for this component are outlined in Table 1.

The comprehensive process in medical decision making is an area that reflects evaluating, testing and treatment, and providers should take precaution to monitor practice improvement to avoid unnecessary audits and/or coding adjustments.

Keep in mind that Medicare and private payers incorporate medical necessity as a criterion for payment in addition to the individual requirements of the CPT codes. Thus, when CMS states that the medical necessity requirement must be met “in addition to the individual requirements of a CPT code,” this means, even if a service meets the technical requirements of a CPT code level (including medical decision making), that level may be higher than the medical necessity of the service, which may make it unpayable by Medicare at that level. Many third-party payers have specific coverage rules regarding what they consider medically necessary, or have riders and exclusions for specific procedures. Third-party payers may have a specific exclusion for procedures they consider experimental or unproven for a specific diagnosis or procedure, and it is imperative practices understand the protocols for billing a service.

For additional information or questions on coding, billing and auditing, contact Antanya Chung, CPC, CPC-I, CRHC, CCP, at [email protected].