This is part two of a four-part series on the 2006 Rheumatology Workforce Study.

In 2005, when the ACR commissioned its first workforce study in 10 years, it suspected—correctly—that the demand for rheumatology services would increasingly exceed supply over the next several years. In fact, rheumatologists are keenly aware that patients are already waiting longer to see a specialist. “The problem is not specific to rheumatology; it really involves all healthcare delivery in this country,” says Timothy Harrington, Jr., MD, head of the rheumatology section at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Dr. Harrington was a member of the ACR group that spearheaded the workforce study effort, and he has spent the past 10 years redesigning his own rheumatology practice to reduce wait times and deliver higher quality patient care.

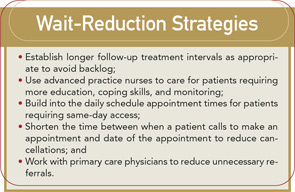

The workforce study report suggests practice redesign—for example, implementing patient screening and employing advanced practice nurses and physicians assistants (PAs)—is one way to minimize the effects of the workforce shortage.

“The question that we all must answer is how many rheumatologists are really needed for people with rheumatology disease,” Dr. Harrington says. “We have not defined ‘necessary care’ and the result is a high level of inefficiency.”

Practice Efficiency

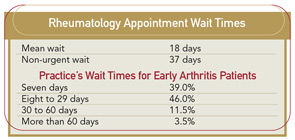

The workforce study highlights wait times for patients as a strong indication of excess demand. The current wait time for new rheumatology patients is higher than for general medicine and other specialty referrals, such as cardiology and gastroenterology.

The workforce report notes rheumatologists try their best to see early arthritis patients quickly in order to prevent joint damage, although some practices still have wait times over two months for these patients.

Nearly all (97%) of the rheumatology practices that responded to a survey conducted as part of the workforce study report that they accept new patients. However, nearly half (48%) restrict access by requiring a referral from a primary care physician. Despite this requirement, Dr. Harrington emphasizes that approximately half of all new patients to rheumatology practices show up without medical records and a majority (80%) do not come to the specialist with a written referral. This automatically triggers the need for a follow-up appointment, he says.

“That almost half of rheumatologists report limiting access based on referral and almost half report wait times for non-urgent patients exceeding four weeks suggests that there is considerable excess demand for rheumatology services,” notes the rheumatology survey final report. “The current supply of rheumatologist visits is not equal to the demand for those visits such that rheumatologists are limiting access through requiring referrals or having long wait times for appointments.”

The workforce survey also asked practices if they planned to hire now or in the next five years—and the response is another indicator that practice redesign is needed. The survey asked rheumatologists if they planned to hire now or in the future, a rheumatologist, a pediatric rheumatologist, a PA, or a nurse practitioner (NP). The results indicate a strong demand for rheumatology services.

Change Your Practice

In the article “Pre-Appointment Management of New Patient Referrals in Rheumatology: A Key Strategy for Improving Health Care Delivery,” Dr. Harrington and Michael B. Walsh, DO, discuss implementation of a screening process for newly referred patients. This article, profiled in the workforce study report, outlines strategies that have been implemented by many ACR members to respond to the need for practice redesign. It listed three general strategies for improvement:

- New patient screening;

- Improved appointment scheduling; and

- Improved quality of care for chronically ill patients.

Dr. Harrington and others have implemented a screening process for all new patients that follows an algorithm for determining if and when the patient should be seen by the rheumatologist, referred to another specialist or pain center, or referred back to the primary care physician. The rheumatologist reviews each case to make this determination. Some of the patients not seen by the rheumatologist were referred to an orthopedist or spine program. “Others were assured that their treatment through the primary care physician was appropriate,” the report notes. “The review of patient records prior to the first appointment had other benefits … it allowed the rheumatologists more information on the patient prior to the appointment so that they could decide whether a brief or longer visit was needed. Also, with the records on hand, duplicate testing occurred less frequently.”

Dr. Harrington tells The Rheumatologist that he was forced to look at redesigning his own practice when he lost the services of an orthopedic spine specialist and wait times in his practice went from two months to six months.

At that time, he and colleagues decided to take a deeper look at the 120 patients on his six-month waiting list and found that half had either gotten better or seen another physician during the six-month period. “As rheumatologists, we need to enforce clinical practice guidelines,” says Dr. Harrington. “We have to learn to do a better job of pre-appointment assessment and management. For instance, if we get a call from a patient with back pain for three days after lifting, the appropriate clinical assessment would send that patient to the primary care physician.”

The study report highlights one rheumatology practice that tested other strategies to reduce wait time for early arthritis patients with success.

“Within several months of implementing this strategy, the wait time for an appointment in the department fell from about 60 to 25 days,” according to the workforce study report. “Nine months after implementation, wait times declined to two days. The department also saw improvements in cancellation rates which fell from about 40% to 20%.”

Likewise, the report cited a chronic care model developed in the 1990s as one that has been used by some rheumatologists. This model suggests that care needs to be changed from episodic to continuous treatment. One idea proposed is to encourage the implementation of the chronic care model into current medical education curriculum. “Through this implementation, students will learn how the biology of chronic disease evolves and the [effects] of treatment as well as how physicians can efficiently use available treatment and other resources.”

The ACR workforce report suggests that physician specialists can improve their ability to treat patients by creating a multidisciplinary team approach to care management and, as part of this team, should hire a nurse practitioner or a physician assistant to perform routine duties that are now covered by the rheumatologist.

Another factor cited in the study report is the effect of Medicare coverage on practice. Changes in Medicare payment policy and the policies of other insurers for rheumatology services are important considerations. These include a cut in Medicare reimbursement for drug costs for on-site infusion services from 95% to 85% of the wholesale price as of January 2004. At the same time, as part of the provisions of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, Congress increased reimbursement for practice expenses by 32% in 2004. Beginning in 2005, a formula called the average sales price is used to calculate reimbursement. The report states this new formula increases payment to physicians to 106% of the average sales price.

However, “the change in reimbursement for on-site infusion is likely to result in decreased reimbursement of infusion drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. This may result in rheumatologists needing to reduce the number of sites where a patient can receive infusions as well as the size of the staff at the sites,” the report notes.

Teamwork on Patient Histories

Dr. Harrington notes that one particular area in which rheumatologists can use the NP or PA to help is in taking the patient’s medical history. First, he stresses, patients must bring all of their records—including lab results and X-ray films—with them to the initial appointment. Second, many rheumatologists are still doing their own narrative histories with patients, but having a PA or NP do this can save an average of 10 minutes per patient and close to double the number of patient appointments available in a day.

Dr. Harrington recommends using a standardized history form that uses branching logic. Give the form to patients while they are in the waiting room and have NPs and PAs who have training in the protocols assist the patient and then provide a summary to the rheumatologist before the actual patient time with the doctor. The standard form has a disease activity score that the NP or PA then can use to qualify the patient’s needs. “We need to learn how to function like dentists and use other clinical staff (e.g., the dental hygienist) to share the workload,” says Dr. Harrington.

He also urges rheumatology practices to switch to electronic medical records (EMRs). (See “Go Digital,” p. 1.) Despite their proven ability to enhance practice management and streamline patient care, only 15% of rheumatologists currently use EMRs.

The technological changes like EMRs and changes in practice organization and design provide a backdrop for fundamental workforce supply and demand and for the primary goal of improving patient outcomes.

“All of the things that we have identified as improvements in practice also improve patient outcomes,” says Dr. Harrington. He stresses that the ACR workforce study report is just the opening round of the discussion on how to further improve.

Retirement Effects

The workforce study highlighted the need to increase the number of U.S. rheumatologists in order to meet future demand for services. One key factor in whether the supply of specialists in the future will meet the demand is the number of rheumatologists planning to retire in the next five to 10 years. Rates of retirement are not available for rheumatologists specifically, but general data on physician specialists suggests what the workforce study called “substantial declines” in rheumatologists between age 59 and 68. “Beyond age 68, the labor force participation rates level off with about 60% of male and 40% of female professionals continuing to participate in the labor force through age 75 at which point the predictive model assumes all rheumatologists will have retired.”

The workforce survey asked respondents when they planned to reduce their work efforts either prior to or at full retirement. Younger rheumatologists plan to reduce work effort earlier than their older counterparts, as do women. This data may be biased because any physicians currently older than 60 who have retired were not counted in the results. Overall, rheumatologists expressed satisfaction with their current work level and environment. About half said they would like their current workload to remain the same; the other half said they wanted their workload to decrease.

With new efforts to improve chronic care management of patients with rheumatic diseases as well as to promote early screening and prevention if possible, Dr. Harrington says the challenge to align clinical practice in a way that meets the needs of patients and rheumatologists in practice is a long-term project. “We continue to move from reactive medicine to primary prevention. How will the system manage this change?” he says. “The impact of current and pending technological advances and practice efficiencies is difficult to quantify,” says the ACR report. “Moreover, future changes not anticipated here will undoubtedly have effects.”

Terry Hartnett is writing the workforce study series.