Image Credit: BioMedical/shutterstock.com

Case report: A 27-year-old male was referred to the rheumatology outpatient department in February 2015 from the urology department after complaining of recent-onset uncontrolled hypertension (220/160 mmHg), headache and vomiting.

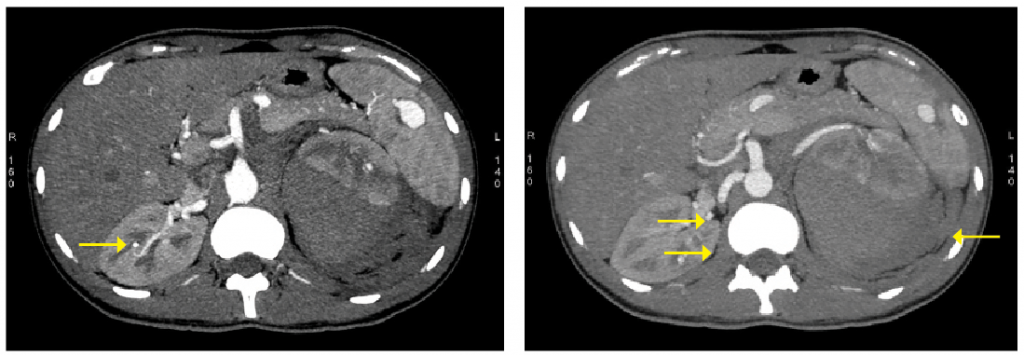

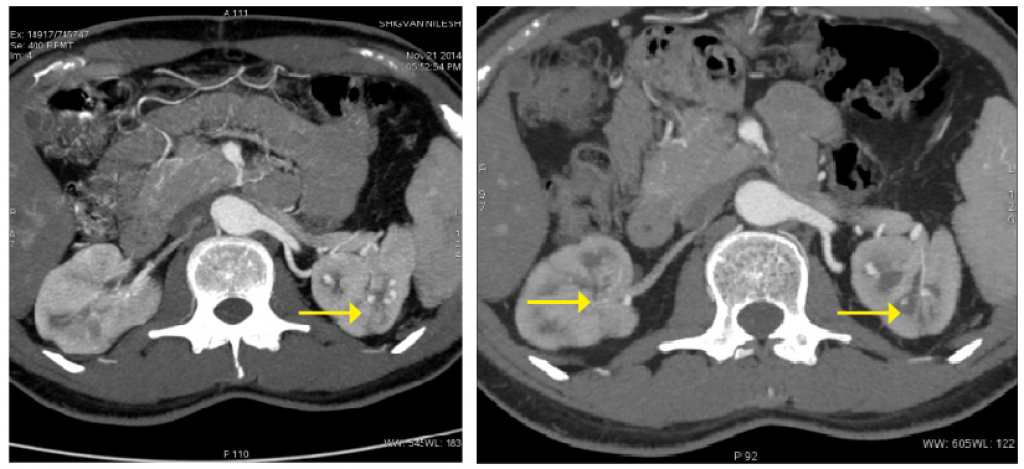

In 2010, he was admitted to the urologist for sudden-onset left lumbar region pain and recent-onset hypertension. Clinical examination and the blood tests were normal. CT angiography of the abdomen suggested a ruptured aneurysm with subcapsular and para-renal hematoma around the left kidney. Multiple aneurysms were present in the intra-renal vessels on the left and right kidneys. Aneurysms were also present in the lower pole of the spleen and branches of the splenic artery. The abdominal aorta and its major vessels were normal at their origin (see Figures 1 & 2).

Emergent exploratory laparotomy was performed, with evacuation of the hematoma. A diagnosis of medium vessel vasculitis–polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) was made, and immunosuppressive therapy with steroids was advised at the time of discharge. However, the patient had not participated in follow-up visits until the present consultation.

(click for larger image)

Figure 1: A splenic, right renal aneurysm with left para-renal hemorrhage is shown in the CT.

Figure 2: Multiple right renal aneurysms with left para-renal hemorrhage are shown in the CT.

Upon presentation, the patient’s examination was normal except for hypertension. Inflammatory markers and all other labs were normal. Repeat CT angiography showed the presence of multiple new aneurysms involving peripheral intra-renal branches on both sides (see Figure 3).

Given the presence of new aneurysms and uncontrolled hypertension, the patient was started on oral prednisolone at 40 mg/day and was given three pulses of IV cyclophosphamide, each at 500 mg, two weeks apart. Following the three pulses, he was asymptomatic, his inflammatory markers were normal, and his blood pressure had been reduced to 170/90 mmHg.

(click for larger image)

Figure 3: Pretreatment, multiple bilateral intra-renal aneurysms are present.

Figure 4: Post-treatment, significant resolution of the aneurysms bilaterally is apparent.

A repeat CT angiography was performed to monitor response to treatment and help guide further treatment. The repeat scan demonstrated significant reduction in the size and number of aneurysms bilaterally (see Figure). Thus, we decided to continue treatment with three additional pulses of cyclophosphamide.

Discussion

PAN is a necrotizing systemic vasculitis involving the medium and small arteries, characterized by the presence of aneurysms and stenosis of medium-sized visceral arteries on angiography, absence of glomerulonephritis and negative serology for ANCA.1 The classification criteria for PAN were proposed by the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC 2012), the American College of Rheumatology (ACR 1990) criteria and the French Vasculitis Study Group criteria (2008).1,2,8 There are no diagnostic criteria.3

PAN is associated with hepatitis B and other viral infections. Diagnostic clues include the presence of systemic features, such as fever, malaise, weight loss; ischemic symptoms, including myalgia, renovascular hypertension, severe abdominal pain, testicular pain, livedo reticularis and digital gangrene; and symptoms secondary to ruptured aneurysms, including intra-abdominal and renal hemorrhage.

It’s imperative to also consider important differential diagnoses that cause aneurysms, including other types of small and large vessel vasculitis, infections and non-inflammatory vasculopathies, because treatment differs according to the cause.

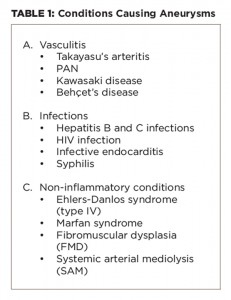

Important differential diagnoses that cause aneurysms are given in Table 1.

Aneurysms occur in the other forms of vasculitides, as well. In Takayasu’s aortoarteritis (large vessel vasculitis), aneurysms are well described in the aorta and its major branches in the proximal portions of these vessels on angiography, and rarely, there are aneurysms of the visceral arteries.4 It usually presents with limb claudication, CNS ischemic symptoms, absent or unequal pulsations and hypertension. Pulmonary artery aneurysms presenting in the midpart of the pulmonary artery, presenting with hemoptysis is typical of Behçet’s disease (variable vessel vasculitis) and is associated with the predominant mucocutaneous and ocular features.1 Kawasaki disease (medium vessel vasculitis) is characterized by coronary artery aneurysms in children.1

Non-inflammatory vasculopathies can cause aneurysms, which could be asymptomatic. They include fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), systemic arterial mediolysis (SAM), Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) type IV.5

FMD typically affects young females, preferentially affects renal arteries with string of bead appearance on angiography and may be asymptomatic or may lead to hypertension. However, isolated intra-parenchymal renal aneurysms are rare in FMD. Similarly, in Marfan syndrome the aorta is predominantly affected by aneurysms and dissection of the involved vessels, and other clinical features are present. In EDS type IV, aorta, celiac artery, splanchnic vessels and renal vessels are most commonly affected. Again, the lesions in EDS are more proximal, with increased risk of aneurysms, dissections and rupture.

It’s imperative to also consider important differential diagnoses that cause aneurysms, including other types of small & large vessel vasculitis, infections & non-inflammatory vasculopathies.

Back to the Case

In our patient, there were no clues (i.e., clinical, laboratory or imaging) to suggest these other differentials. Although there were no other clinical features of PAN and the inflammatory markers were normal, the diagnosis of PAN was tenable.2

Although there were no other clinical features of PAN—the inflammatory markers were normal and viral serologies were negative—in the view of hypertension, presence of multiple intra-renal and splenic aneurysms on CT angiography, abdominal hemorrhage and response to immunosuppressive treatment, the diagnosis of PAN was tenable.2,6-8

Comparison with earlier CT angiography plates did show presence of new aneurysms, and because a past history of near-fatal aneurysmal rupture existed, after an adequate explanation to the patient, a decision was taken to treat him as active disease. Because the viral serologies were negative, cyclophosphamide and steroids were instituted.9

The other important aspect of this case was to assess disease activity. ESR/CRP was normal, and the patient could not afford a positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance angiography (PET/MR), which can help assess disease activity. Thus, after three doses of intravenous cyclophosphamide, a repeat CT angiography was performed, which showed significant reduction in the size and number of aneurysms.

This highlights the difficulty of monitoring response to treatment in the face of normal inflammatory markers and the role of imaging in monitoring disease activity in patients with polyarteritis nodosa.

Dr. Parikh

Dr. Yathish

Dr. Sagdeo

Taral Parikh, MD, G.C. Yathish, MD, and Parikshit Sagdeo, MD, are rheumatology DNB students at Hinduja Hospital in Mumbai, India.

Dr. Canchi

Balakrishnan Canchi, MD, is chief of rheumatology at Hinduja Hospital.

Dr. Mangat

Gurmeet Mangat, MD, is a consultant rheumatologist at Hinduja Hospital.

Key Points

- Renal artery involvement in PAN is in the form of intra-renal aneurysms, differentiating it from other mimics.

- Assessing disease activity of such patients may be difficult.

- Consider such aneurysms as evidence of active disease, and treat them accordingly.

- Repeat imaging in such patients could show a reduction in the aneurysms’ size, number or both.

References

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):1–11.

- Hunder GG, Arend WP, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of vasculitis. Introduction. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Aug;33(8):1065–1067.

- Henegar C, Pagnoux C, Puéchal X, et al. A paradigm of diagnostic criteria for polyarteritis nodosa: Analysis of a series of 949 patients with vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 May;58(5):1528–1538.

- Kerr GS, Hallahan CW, Giordano J, et al. Takayasu arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 1994 Jun 1;120(11):919–929.

- Slavin RE. Segmental arterial mediolysis: Course, sequelae, prognosis, and pathologic- radiologic correlation, Cardiovasc Pathol. 2009 Nov–Dec;18(6):352–360.

- Hekali P, Kajander H, Pajari R, et al. Diagnostic significance of angiographically observed visceral aneurysms with regard to polyarteritis nodosa. Acta Radiol. 1991 Mar;32(2):143–148.

- Ozaki K, Miyayama S, Ushiogi Y, et al. Renal involvement of polyarteritis nodosa: CT and MR findings. Abdom Imaging. 2009 Mar–Apr;34(2):265–270.

- Pagnoux C, Seror R, Henegar C, et al. Clinical features and outcomes in 348 patients with polyarteritis nodosa: A systematic retrospective study of patients diagnosed between 1963 and 2005 and entered into the French Vasculitis Study Group Database. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Feb;62(2):616–626.

- de Menthon M, Mahr A. Treating polyarteritis nodosa: Current state of the art. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011 Jan–Feb;29(1 Suppl 64):S110–S116.