Discovered more than 3,000 years ago, colchicine is one of the oldest drugs still in use today. Like most old remedies, colchicine is a chemical substance found in many plants, most notably in colchicum autumnale, known as wild saffron or autumn crocus. It was mentioned in the oldest Egyptian medical text, Ebers Papyrus (circa 1550 B.C.), where it was described for the use of pain and swelling.1

Discovered more than 3,000 years ago, colchicine is one of the oldest drugs still in use today. Like most old remedies, colchicine is a chemical substance found in many plants, most notably in colchicum autumnale, known as wild saffron or autumn crocus. It was mentioned in the oldest Egyptian medical text, Ebers Papyrus (circa 1550 B.C.), where it was described for the use of pain and swelling.1

As early as the 1st century A.D., Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician and pharmacologist, describes the use of colchicum to treat gout in his pharmacopeia, De Materia Medica.2

Colchicine’s name may come from its use as a poison in the district of Colchis of ancient Greek. Medea, the sorceress daughter of the king of Colchis, used it as one of her poisons, and it was referred to in Greek mythology as “the destructive fire of the Colchicon Medea.”1,2

Over the course of years, the drug has been described in various texts from Persia and Turkey, and it was noted in the London Pharmacopeia in 1618.2

In the 18th century, a French military officer, Nicolas Husson, used colchicine as the main ingredient in Eau Medicinale, a product he developed as a commercial remedy to treat gout. Benjamin Franklin used this product successfully to treat his own gout and is credited with introducing colchicine to the U.S.1

Colchicine was first isolated in 1820 by French chemists Pierre-Joseph Pelletier and Joseph-Bienaimé Caventou, and a purified active ingredient named colchicine was developed in 1833 by Philipp Lorenz Geiger.3

Despite colchicine’s long history of use, it was not until 2009 that the U.S. Food & Drug Administration approved colchicine to treat gout and familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) under the Unapproved Drugs Initiative.4 Beyond gout and FMF, colchicine is widely used to treat a variety of dermatologic conditions, and its role is being investigated for the treatment of coronary artery disease and even COVID-19 infection.

Mechanism of Action

Colchicine binds to tubulins, blocking the assembly, polymerization and—at higher concentrations—depolymerization of microtubules. Colchicine has multiple effects on the function of the immune system. It inhibits neutrophils’ chemotaxis, adhesion, mobilization and superoxide anion production. It also inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome complex that mediates interleukin 1β activation. Because it binds to tubulin, colchicine interferes with mitosis.

Despite its antimitotic effect, the efficacy of colchicine in curbing the inflammatory process without prohibiting toxicities may be due to its tendency to highly concentrate in the neutrophils, possibly related to their low expression of ABCB1 drug transporter gene.5,6

Further, Chia et al. showed that colchicine was selective in inhibiting monosodium urate (MSU) induced superoxide production by neutrophils at much lower doses than those required to inhibit neutrophil migration in vivo.7 Nevertheless, neutrophils treated with colchicine were still able to mount superoxide production in response to stimuli other than MSU. Thus, the use of colchicine in the treatment of gout at low, non-toxic doses would have no impact on superoxide production by other stimuli.7

Colchicine exerts an additional anti-inflammatory effect by blunting tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α-induced activation of macrophages. It reduces TNF receptors on macrophage surfaces and may also have a role in inhibiting both cell-mediated immunity and antibody selection. It also inhibits the expression of IL-2 receptor on activated T lymphocytes and down-regulates ICAM-1 and E-selectin on endothelial cell surfaces, and induces shedding of neutrophil adhesion molecules L-selectin, which interfere with adhesiveness and further recruitment of neutrophils.

Finally, colchicine inhibits transforming growth factor β and directly suppresses specific genes, like fibronectin, thus giving colchicine antifibrotic properties.5

Colchicine is a relatively well-tolerated drug, with the most common side effect being diarrhea, which is noted in about 23% of patients receiving low to moderate doses.

Current Uses

Below, we discuss various off-label and novel applications of colchicine, in addition to reviewing the FDA-approved indications.

I. FDA-approved indications for the use of colchicine:8

A. Treatment of acute gout: Colchicine is an effective treatment for acute gout if used soon after initiation of the gout attack.9,10 It works well even when used at a lower dose, as described in the AGREE trial and is well tolerated at that dose.11 It can be safely used in patients with chronic kidney disease, which is a contraindication for the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the treatment of gout; dose adjustment is necessary in such situations.12

B. Chronic prophylaxis against gout: Although the ACR recommends allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor, as a typical drug for prophylaxis against future gout attacks, colchicine has two unique roles: 1) It can be used in conjunction with allopurinol until target serum uric acid levels are reached, and 2) colchicine can be used for chronic prophylaxis in individuals who are intolerant of uric acid lowering or have contraindications to allopurinol’s use.

C. Familial Mediterranean fever: Colchicine can be used at doses up to 2.4 mg/day in divided doses to treat this rare condition, which affects individuals of certain ethnicities, including Ashkenazi Jews, Italians, Greeks, Spaniards and Cypriots. It has also been approved in children with this condition.13

II. Non-FDA-approved indications for the use of colchicine:

A. Role of colchicine in COVID-19: Given the anti-inflammatory properties of colchicine, there was enthusiasm to study its effect on COVID-19. A recent retrospective cohort study showed colchicine use was associated with reduced mortality and faster recovery in COVID-19 patients.14

Another recent trial concluded that colchicine reduced the length of both oxygen therapy and hospitalization.15 The COLCORONA trial showed that, for non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19, colchicine reduced the composite rate of death or hospitalization.16 However, although the final results of the RECOVERY trial are yet to be published, the preliminary analysis of data failed to show a significant difference in the primary endpoint of 28-day mortality of colchicine vs. usual care alone.17

Multiple trials are in progress, as noted on clinicaltrials.gov.18

B. Cardiac conditions: Multiple in vitro animal models and observations in patients treated with colchicine have demonstrated that colchicine has antifibrotic effects and plays a role in improving endothelial dysfunction, inhibition of intimal hyperplasia, suppressing smooth muscle cell proliferation and reducing the expression of inflammatory proteins, such as TNF-α and NF-κB, among others.5 This encouraged investigations of colchicine’s role in pericarditis and atherosclerosis.

1. Colchicine proved efficacious in treating pericarditis when added to the conventional anti-inflammatory regimen.19

2. Interestingly, the COLCOT trial showed that treating patients with recent myocardial infarction with low-dose colchicine, 0.5 mg daily, significantly lowered the risk of ischemic cardiovascular events.20 However, the Australian COPS Randomized Clinical Trial did not replicate such a result and concluded the use of colchicine as secondary prevention after acute coronary syndrome was associated with an increased rate of mortality.21 Further studies are required to determine the safety and benefit of colchicine after a myocardial infarction.

C. Other arthritic conditions—calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) arthritis: Although minimal literature supports the use of colchicine in patients with CPP arthropathy, the shared mechanism of inflammation induced by CPP and urate crystals support the logic of its use.

In a randomized controlled trial of 39 patients with knee osteoarthritis with persistent inflammation induced by CPP, the addition of colchicine to intra-articular glucocorticoids was superior to intra-articular glucocorticoids alone.22

In another clinical trial among patients with knee osteoarthritis, the addition of colchicine to nimesulide was superior to nimesulide alone.

In 2011, EULAR recommended colchicine in patients with CPP arthropathy based on expert opinion.23

D. Dermatologic indications: Very limited data exist for the use of colchicine in dermatologic conditions, yet colchicine is used widely for a variety of dermatologic diseases, including several that rheumatologists frequently see. Neutrophilic dermatoses, such as Sweet’s syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum and Behçet’s disease, as well as neutrophilic infiltrative diseases, such as pustular psoriasis, erythema nodosum, cutaneous vasculitis and recurrent aphthous stomatitis, have all been successfully treated with colchicine. It has also been used in neutrophilic bullous disorders, such as dermatitis herpetiformis, and other conditions, such as actinic keratosis and hidradenitis suppurativa. Some initial studies have also assessed the use of colchicine in scleroderma.24-27

Adverse Drug Reactions

Colchicine is a relatively well tolerated drug, with the most common side effect being diarrhea, which is noted in about 23% of patients receiving low to moderate doses. In patients using higher doses, more than 2–3 mg/day, the incidence of diarrhea could increase to about 80%. Other gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, have also been noted.5,11

Aside from higher doses, the presence of renal failure, liver failure and concurrent use of CYP3A4 inhibitors could increase the risk of gastrointestinal side effects.28 Given how common statin use is in colchicine users, it is worthwhile to note the potential drug-drug interaction with certain statins that are substrates for CYP3A4 (e.g., atorvastatin and simvastatin) and consider replacing them with a statin that is not metabolized by CYP3A4 (e.g., pravastatin or rosuvastatin).28

Other side effects of importance to note include cytopenia, bone marrow suppression and vacuolar myopathy. These are quite rare.5,29

Unapproved Drugs Initiative & Cost

Despite being used successfully to treat gouty arthritis for a long time and its availability as a generic prescription drug in the U.S. since the 19th century, colchicine was not approved by the FDA until 2009. In 1938, the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act required all new drugs be approved by the FDA before being released to the market. In the 1960s, the agency embarked on evaluating the safety and efficacy of older drugs. While the FDA approved a combination pill containing colchicine and probenecid for use in gout, monotherapy of colchicine was not approved.

In 2006, the FDA launched the Unapproved Drugs Initiative, with a primary intention of documenting supporting data for several drugs that remained in the market continually, even before the agency began reviewing safety and effectiveness data in 1938.30 In exchange, the FDA offered market exclusivity to the first manufacturers of the product.

A clinical trial assessing the efficacy of colchicine in gout was completed, and the FDA approved colchicine under the brand name Colcrys for the treatment of acute

gout, granting Takeda Pharmaceuticals a three-year period of market exclusivity for gout and a seven-year exclusivity for use in FMF under the Orphan Drug Act.31 In 2010, the FDA ordered other manufacturers to stop manufacturing their products. In 2011, branded colchicine was the only formulation available in the U.S.32

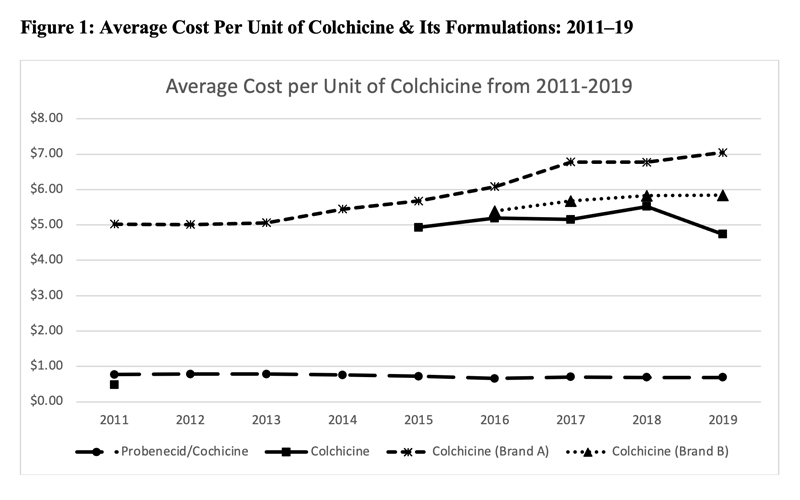

This led to a significant increase in the price of colchicine. Figure 1 (below) shows the average cost per unit of various formulations of colchicine as noted in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Part D spending files. Although data prior to 2011 were unavailable, the cost of generic colchicine in 2011 was $0.48. During the period of market exclusivity, the unit cost of branded colchicine soared to well over $5.

In 2015, generic colchicine was once again available in the market; however, despite the availability of alternative formulations of colchicine, the price of colchicine remained high.33,34

In 2019, there were two branded formulations of colchicine and generic colchicine was being manufactured by more than six companies, yet the unit cost was over $4.74. The cost of branded colchicine was $7.03.

The unit cost of probenecid-colchicine over this entire study period remained at approximately $0.70.

A total of 21 drugs received approvals from 2008–17 under the Unapproved Drugs Initiative, and two were granted exclusivity under the Orphan Drug Act. Eight of the 21 were self-administered agents, including morphine sulfate, oxycodone hydrochloride and atropine sulfate eye drops. Competition amongst manufacturers of these products was significantly reduced, and although not as remarkable as colchicine, several products saw an increase in unit price.30

In November 2020, the FDA decided to terminate the Unapproved Drug Initiative. In a report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the FDA, it stated several reasons for such an action. In addition to raising the costs of several drugs, including colchicine, the market exclusivity provided under the Unapproved Drugs Initiative created shortages of various drugs.

The report added that the majority of the drugs approved under this initiative were supported by literature reviews and bioequivalence to older drugs, with very little added in terms of new clinical trial evidence.

As a consequence, the cessation of this initiative will likely reduce the burden on American taxpayers and increase access to these drugs.35 It is presently unclear what will replace the Unapproved Drug Initiative.

Conclusion

Colchicine is one of the oldest remedies still in use today, with the potential for multiple indications. The anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects it confers, with a relatively favorable safety profile, make it an ideal drug for several rheumatic and non-rheumatic conditions. Although the cost of this very old drug remains inexplicably high, it is being investigated for several rheumatic and non-rheumatic conditions.

Ibrahem Salloum, MD, is a hospitalist and assistant professor (clinician-educator) with the Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine at the Warren Alpert School of Medicine, Brown University, Providence, R.I. He provides inpatient care at The Miriam Hospital in Providence and has an interest in caring for patients with rheumatic diseases.

Deepan S. Dalal, MD, MPH, has been a faculty member in the Department of Medicine, Rheumatology Section at the Warren Alpert School of Medicine for the past five years. He sees patients in the general rheumatology clinic at Brown Medicine Patient Center and has a special interest in musculoskeletal ultrasound. He focuses on health services and outcomes research and is particularly interested in geriatric patients suffering from inflammatory arthritis.

Deepan S. Dalal, MD, MPH, has been a faculty member in the Department of Medicine, Rheumatology Section at the Warren Alpert School of Medicine for the past five years. He sees patients in the general rheumatology clinic at Brown Medicine Patient Center and has a special interest in musculoskeletal ultrasound. He focuses on health services and outcomes research and is particularly interested in geriatric patients suffering from inflammatory arthritis.

References

- Nerlekar N, Beale A, Harper RW. Colchicine—a short history of an ancient drug. Med J Aust. 2014 Dec 11;201(11):687–688.

- Hartung EF. History of the use of colchicum and related medicaments in gout; with suggestions for further research. Ann Rheum Dis. 1954 Sep;13(3):190–200.

- Roddy E, Mallen CD, Doherty M. Gout. BMJ. 2013 Oct 1;347:f5648.

- Roubille F, Kritikou E, Busseuil D, Barrere-Lemaire S, Tardif JC. Colchicine: An old wine in a new bottle? Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2013;12(1):14–23.

- Leung YY, Yao Hui LL, Kraus VB. Colchicine—Update on mechanisms of action and therapeutic uses. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015 Dec;45(3):341–350.

- Sardana K, Sinha S, Sachdeva S. Colchicine in dermatology: Rediscovering an old drug with novel uses. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020 Sep 19;11(5):693–700.

- Chia EW, Grainger R, Harper JL. Colchicine suppresses neutrophil superoxide production in a murine model of gouty arthritis: A rationale for use of low-dose colchicine. Br J Pharmacol. 2008 Mar;153(6):1288–1295.

- COLCRYS. accessdata.fda.gov. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/022352s017lbl.pdf.

- Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: Therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Oct;64(10):1447–1461.

- Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Jan;76(1):29–42.

- Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, et al. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: Twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Apr;62(4):1060–1068.

- Vargas-Santos AB, Neogi T. Management of gout and hyperuricemia in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 Sep;70(3):422–439.

- Ozkaya N, Yalcinkaya F. Colchicine treatment in children with familial Mediterranean fever. Clin Rheumatol. 2003 Oct;22(4–5):314–317.

- Manenti L, Maggiore U, Fiaccadori E, et al. Reduced mortality in COVID-19 patients treated with colchicine: Results from a retrospective, observational study. PLoS One. 2021 Mar 24;16(3):e0248276.

- Lopes MI, Bonjorno LP, Giannini MC, et al. Beneficial effects of colchicine for moderate to severe COVID-19: A randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. RMD Open. 2021 Feb;7(1):e001455.

- Tardif JC, Bouabdallaoui N, L’Allier PL, et al. Efficacy of colchicine in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19 [preprint]. medRxiv2021. 2021 Jan 27.

- Robinson J. RECOVERY trial halts recruitment to colchicine arm because of a lack of ‘convincing’ evidence. Pharm J. 2021 Mar 8.

- clinicaltrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=colchicine+covid&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=.

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cemin R, et al. A randomized trial of colchicine for acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 17;369(16):1522–1528.

- Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019 Dec 26;381(26):2497–2505.

- Tong DC, Quinn S, Nasis A, et al. Colchicine in patients with acute coronary syndrome: The Australian COPS randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2020 Nov 17;142(20):1890–1900.

- Das SK, Mishra K, Ramakrishnan S, et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the slow-acting symptom modifying effects of a regimen containing colchicine in a subset of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002 Apr;10(4):247–252.

- Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. EULAR recommendations for calcium pyrophosphate deposition. Part II: Management. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Apr;70(4):571–575.

- Callen JP. Colchicine is effective in controlling chronic cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985 Ag;13(2 Pt 1):193–200.

- Robinson KP, Chan JJ. Colchicine in dermatology: A review. Australas J Dermatol. 2018 Nov;59(4):278–285.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucglà A, et al. Colchicine in the treatment of cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Results of a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 1995 Dec;131(12):1399–1402.

- Sullivan TP, King LE Jr., Boyd AS. Colchicine in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998 Dec;39(6):993–999.

- Slobodnick A, Shah B, Krasnokutsky S, Pillinger MH. Update on colchicine, 2017. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018 Jan 1;57(suppl_1):i4–i11.

- Fernandez C, Figarella-Branger D, Alla P, et al. Colchicine myopathy: A vacuolar myopathy with selective type I muscle fiber involvement. An immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study of two cases. Acta Neuropathol. 2002 Feb;103(2):100–106.

- Gunter SJ, Kesselheim AS, Rome BN. Market exclusivity and changes in competition and prices associated with the US Food and Drug Administration Unapproved Drug Initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 2021 May 17;3211989.

- Kesselheim AS, Solomon DH. Incentives for drug development—The curious case of colchicine. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jun 3;362(22):2045–2047.

- Kesselheim AS, Franklin JM, Kim SC, et al. Reductions in use of colchicine after FDA enforcement of market exclusivity in a commercially insured population. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 Nov;30(11):1633–1638.

- Gallegos A. Court allows generic colchicine to enter market 2015. Rheumatology News. 2015 Jan 28.

- McCormick N, Wallace ZS, Yokose C, et al. Prolonged increases in public-payer spending and prices after unapproved drug initiative approval of colchicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Feb 1;181(2):284–287.

- Termination of the Food and Drug Administration’s unapproved drugs initiative; request for information regarding drugs potentially generally recognized as safe and effective. Department of Health and Human Services. hhs.gov. 2020 Nov 20.