Rheumatologists and neurologists are old friends. Practitioners of both fields have long shared a number of diagnoses, and referrals from one specialist to the other are frequent, such as for central nervous system (CNS) conditions, including giant cell arteritis, primary angiitis of the CNS, Call-Fleming syndrome, Susac’s syndrome and neuropsychiatric lupus. For the peripheral nervous system, shared spaces include evaluations of patients with mononeuritis multiplex or sensory neuropathy.

Rheumatologists and neurologists are old friends. Practitioners of both fields have long shared a number of diagnoses, and referrals from one specialist to the other are frequent, such as for central nervous system (CNS) conditions, including giant cell arteritis, primary angiitis of the CNS, Call-Fleming syndrome, Susac’s syndrome and neuropsychiatric lupus. For the peripheral nervous system, shared spaces include evaluations of patients with mononeuritis multiplex or sensory neuropathy.

Philip Seo, MD, MHS, director of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Rheumatology Fellowship, spoke with The Rheumatologist about what rheumatologists think neurologists should know to help strengthen the partnership between specialties.

He listed four areas of concerns. Rheumatologists must:

- Understand their limits. Sometimes a rheumatologist can treat only a portion of what’s happening to a patient with rheumatic disease;

- Realize how dependent rheumatologists are on the physical exam;

- Know that nerve conduction studies can be operator dependent; and

- Understand that neurologists and rheumatologists focus on atypical diseases. Communication is key.

“Rheumatologists generally rely on clinical assessment and try not to [request] tests when we feel that the yield [may] be low,” Dr. Seo says. “Neurologists sometimes cast a broad net, which may lead to equivocal tests that are difficult to interpret. As an example, an ANA [antinuclear antibody] test in a patient who presents with joint swelling and a malar rash is an incredibly useful test. An ANA test in a patient without the typical features of lupus may just be noise, because the test is positive in up to one-third of patients without a discernable autoimmune disease.”

Understand Your Limits

Dr. Seo says neurologists may be tempted to think that after a patient has an identified rheumatic condition, it’s smooth sailing for a rheumatologist to treat whatever problems arise. Nope.

“Often, there is a very thin slice of the patient’s problems that I can get under control with immunosuppression,” Dr. Seo says. “Many of the problems that bother the patient the most are a consequence of damage caused by previously active disease, which is no longer responsive to immunosuppression, the consequence of the drugs I use, such as steroid myopathy, or completely unrelated to the patient’s rheumatic disease, even though the patient may think that the problems are linked.”

Neurologists can help set a reasonable expectation about what their rheumatic brethren can achieve.

“My drugs can often halt the progress of a rheumatic disease, but [the treatments] can’t walk back damage that has already taken place [in the body], and they often take months to start working,” Dr. Seo says. “Patients sometimes come into my clinic with the idea that they have the autoimmune equivalent of a pneumonia. And it’s helpful if they realize that, regardless of the final diagnosis, treatment is generally a marathon, not a sprint.”

Importance of the Physical Exam

Dr. Seo says there are only few situations in which he can get a clinical diagnosis based on a lab test, particularly if the patient’s history and physical presentation are not typical. Buttressing test results with the valuable information gleaned from a physical examination is key.

“When I am seeing a patient who has both neurologic and extra-neurologic problems, I cheat. I use the patient’s rash or joint pain or lung infiltrates as a guide to determining if their neurologic disease is also being adequately treated,” he says.

Example: When patients have only neurologic manifestations, such as in Susac’s syndrome, Dr. Seo wants a neurologist to “please pick up the phone and walk me through why you think I need to prescribe cyclophosphamide.” Something that might be an obvious conclusion to a neurologist, may not be as obvious to me. I may be more reluctant to augment immunosuppressive therapy, [because] I have developed a healthy respect for all of the complications associated with these drugs.”

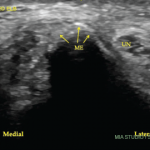

Nerve Conduction Studies Can Be Operator Dependent

Neurologists should not be offended when rheumatologists question certain decisions. Dr. Seo says, “Nerve conduction studies are not perfect tests, inflammatory myopathy can be patchy and hard to find with blind biopsies, and the yield of sural nerve biopsy for vasculitic neuropathy is low. Even with tests that should be giving us definitive answers, there is often room for interpretation and doubt.”

Dr. Seo adds, “Knowing this, please don’t be insulted if I ask you to reconsider a diagnosis that doesn’t seem likely to you.”

Focus on Atypical Diseases

Dr. Seo notes that both specialties focus on the “business of evaluating patients with rare diseases.” But practicing rheumatologists must be wary when a neurologist says that because other options have been ruled out, a patient “must have a rheumatic disease.”

“When a rheumatic disease is a diagnosis of exclusion, it is helpful to communicate directly with the treating rheumatologist to ensure we’re all on the same page,” he says. “I largely diagnose rheumatic diseases based on pattern recognition. So when a patient doesn’t look like the last 10 patients I have evaluated with the same condition, I will want to triple check that every other cause has been excluded before I start immunosuppression. It’s the great irony of these conditions that the mimics of rheumatic disease, such as infection and malignancy, often worsen with immunosuppression, and once treatment begins, diagnostic tests become less reliable. So I’m generally reluctant to start aggressive immunosuppression empirically.

“We could certainly do a better job working with each other,” Dr. Seo adds. “In some ways, it’s as if we speak different dialects of the same language—and some ideas translate better than others. One possibility might be to involve each other in our national meetings. I would bet a What Neurologists Wish Rheumatologists Knew symposium would be very popular at the ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, for example.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.