Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) has been recognized as the most common symptomatic form of antibody deficiency diagnosed in adulthood since its first description by Janeway and colleagues.1 The clinical spectrum of CVID is heterogeneous, but this condition is usually characterized by hypogammaglobulinemia and recurrent bacterial infections. However, the phenotypic and immunologic variability of this disease still marks the diagnosis “CVID” as a grab bag for multiple diseases. Thus, the etiology of CVID is believed to be multifactorial and still holds many unanswered questions. Recent discoveries in the molecular genetics and immunologic basis of this disease have shed important new light on its pathogenesis and raised prospects for earlier and better diagnosis and treatment.

CVID affects both genders equally, with an incidence estimated at 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 50,000.2 In a small number of patients, the onset of disease may occur in childhood, but the mean age of onset for the majority of patients is about 23 for men and 28 for women. There is a significant delay—four to six years on average—between the median age of symptom onset and the age at diagnosis.3

Clinical Features

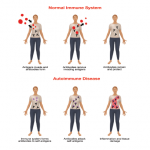

Although the clinical phenotype of CVID may be heterogeneous, one key characteristic of this disease is an impaired ability to produce antibodies. This disturbance manifests in decreased levels of immunoglobulin (Ig) G, IgA, and, sometimes, IgM isotypes and in an impaired or even absent antibody response upon antigenic challenge. This results in a failure to respond to vaccinations and an increased susceptibility to infections. Infections are usually localized in the respiratory tract and a majority of patients have recurrent bronchitis, sinusitis, or otitis (which is more common in childhood-onset CVID), and have had one or more episodes of pneumonia.

Typical pathogens affecting patients with CVID are encapsulated bacteria like Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, or Moraxella catharralis. A significant number of CVID patients also suffer from gastrointestinal tract infections caused by Giardia lamblia, Campylobacter, or Salmonella species. Pulmonary symptoms of CVID may be accompanied by an obstructive lung phenotype (e.g., chronic bronchitis) and asthma. The lung represents the Achilles’ heel of the CVID patient and chronic lung damage (e.g., bronchiectasis, lung fibrosis, and emphysema) is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in the CVID cohort.

The respiratory system of CVID patients may also be affected by granulomatous inflammation, characterized by sarcoid-like lesions in lymph nodes and other histology specimens. This accompanying disease is found in approximately 10% to 22% of CVID patients. In addition to the lung, virtually any other organ system can be affected, but the involvement of lung and liver in particular worsens the patient’s prognosis and is often difficult to treat. High-resolution computer tomography is the method of choice to evaluate and monitor the status and progression of lung-related pathology in CVID patients.