Gastrointestinal diseases are frequent in CVID patients and manifest as chronic diarrhea, malabsorption, and weight loss. A significant number of patients suffer from inflammatory bowel disease.

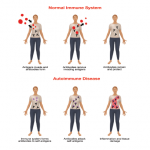

The increased risk of developing autoimmune diseases underscores the sometimes paradoxical immune disregulation observed in CVID patients. The most common autoimmune manifestations in CVID are idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). ITP or AIHA may occur years before a patient presents with an immunodeficiency.4 A subgroup of CVID patients clinically presents with a combination of ITP/AIHA, splenomegaly, and granuloma formation.5 Other observed autoimmune diseases include pernicious anemia, autoimmune thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, and vitiligo.

CVID patients have an increased risk of developing malignancies, especially lymphoma and gastric cancer, and patients should be screened regularly for these potential complications.3

Immunological Features

During the past five decades, numerous studies have identified a plethora of immunological abnormalities in patients with CVID. CVID pathogenesis has been attributed to defects in T cells and their subsets, antigen presenting cells, and B cells. Despite convincing evidence that alterations of T cell function and subset distribution are associated with the CVID phenotype, recent research points to the impaired terminal differentiation of B lymphocytes as the hallmark of the disease.5-7

Several groups have now demonstrated that the formation of memory B cells is severely impaired in the majority of CVID patients and leads to a concomitant depletion of long-lived plasma cells and a drop of serum Ig levels. The altered distribution of B cell subsets observed in CVID patients is now applied in disease classification.5-7

Diagnosis

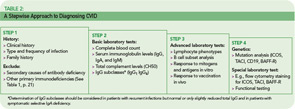

The rare incidence and high clinical variability of CVID can present a diagnostic challenge. Because there is no specific test for diagnosing CVID, diagnosis is made by excluding similar conditions. First, the clinically more frequent secondary causes for hypogammaglobulinemia must be ruled out (See Table 1, below). Then other primary immunodeficiency disorders have to be excluded, and suspected CVID should be validated, as outlined in Table 2 (p. 22).

The first step is the assessment of the clinical and family history, including a detailed description of the type, duration, and frequency of infections. In addition to recurrence of infections, unusual severity and development of complications (e.g., empyema, bronchiectasis) can indicate an underlying immune defect. Identifying underlying pathogens is very helpful in evaluating any immunodeficient patient, with infections by encapsulated bacteria being the most common type in CVID. Whenever possible, use direct detection methods for pathogens (e.g., microbial culture, antigen-ELISA, PCR) to evaluate the cause of infection, because serology is futile in patients with an antibody deficiency.