A systematic assessment of the patient’s immunological status is the next step. This includes basic laboratory analyses such as a complete blood count, serum immunoglobulin levels (IgG, IgA, and IgM), and total complement levels (CH50). The determination of IgG subclasses (IgG1 to IgG4) is especially useful in patients who have only slightly decreased or low-normal IgG serum levels but suffer from recurrent infections.

Next, perform a quantitative flow cytometric analysis of lymphocyte phenotypes. This analysis should include T cell subsets (CD4+, CD8+, and memory) as well as total (CD19+) B cell numbers and B cell subsets. The numbers of class-switched memory B cells (CD27+/IgD–), non-switched memory B cells (CD27+/IgD+), and other peripheral B cell subsets provide useful information. While total numbers of B cells in CVID are usually normal or only slightly reduced in about 90% of patients, class-switched memory B cells are reduced in up to 75% of CVID patients.6,7

Of particular importance is the assessment of specific antibody responses to different antigens (protein and polysaccharide antigens) upon vaccination.8 The results of these tests are helpful in determining whether a patient requires immunoglobulin replacement therapy, especially when a patient is hypogammaglobulinemic but has not yet had recurrent infections.

Genetic testing and specific in vitro tests (e.g., flow cytometry studies of surface markers and specialized functional testing) are available in immunodeficiency centers and specialized laboratories. Although genetic tests for CVID are only accessible to a small subgroup of patients so far, the recent discovery of the first single gene defects permits a definite diagnosis of CVID for the first time.

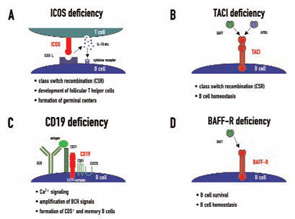

New Genetic Insights in the Pathogenesis of CVID

It has long been known that CVID also has a genetic component. While most cases of this disease occur sporadically, in 10% to 20% of CVID cases, at least one additional family member either suffers from CVID or selective IgA deficiency.9 With a ratio of about 4 to 1, autosomal dominant inheritance is more common than recessive inheritance in CVID families. Genetic linkage studies have revealed that the genetic defect involved in this disease cannot be reduced to a single gene locus.

Candidate loci for CVID have now been demonstrated at the HLA region on chromosome 6, chromosome 4q, and chromosome 16q. This genetic heterogeneity—which probably mirrors the variable clinical presentation of this disease—is further increased by the recent discovery of four candidate genes which were found to be mutated in CVID independently of the results of previous linkage and association studies. These genes—ICOS, TACI, CD19, and BAFFR—encode for cell surface receptors on lymphocytes that play crucial roles either in peripheral B cell development or in B cell function.9