BALTIMORE—In 2009, the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) developed classification criteria that coined the terms axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and non-radiographic axSpA.1 Since then, clinicians and researchers have worked hard to understand these entities and apply this knowledge to accurately diagnose and treat patients with these conditions.

BALTIMORE—In 2009, the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) developed classification criteria that coined the terms axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and non-radiographic axSpA.1 Since then, clinicians and researchers have worked hard to understand these entities and apply this knowledge to accurately diagnose and treat patients with these conditions.

At the 19th Annual Johns Hopkins Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment of the Rheumatic Diseases Symposium, a session titled Updates in Ankylosing Spondylitis and Non-Radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis provided a masterful discourse on this complex, thought-provoking topic.

Overview

Atul Deodhar, MD, professor of medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, began with a helpful summary related to disease manifestations and epidemiology. He explained that axSpA is a chronic, systemic inflammatory disease of the axial skeleton with onset in early adulthood. It can have severe and highly variable disease burden, with significant impacts on quality of life. In addition to inflammatory back pain, patients may experience peripheral inflammatory arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis, uveitis and other ocular manifestations, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, urethritis and even psychologic symptoms, such as anxiety and depression.

The population prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis varies across the globe, ranging from 0.006–0.54%. Within the U.S., the prevalence of axSpA is between 0.9 and 1.4%.2

Dr. Deodhar used the visual graphic of a tree to illustrate why axSpA is so multifaceted. In the roots of the tree are genetic factors, such as the HLA-B27 allele and the ERAP1 gene, which may predispose patients to a higher risk of axSpA but may exist without clinical manifestations of the disease. In the lower trunk of the tree is back pain in general, which may branch into different etiologies, including mechanical back pain, inflammatory back pain and pain from other causes, such as tumors, infections and fractures. The symptom of inflammatory back pain may then branch off into a clinical course with spontaneous remission or a chronic course.

Further down the branch is non-radiographic axSpA, which may also follow a path of spontaneous remission vs. chronic symptoms. Even further down the branch is ankylosing spondylitis, which, in some cases, may involve only the sacroiliac joints. Finally, at the tip of the branch, there is advanced ankylosing spondylitis, with syndesmophytes and other findings of progressive disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of axSpA is challenging. First, diagnosis requires astute pattern recognition, clinical reasoning and the exclusion of other entities that may closely mimic the symptoms of axSpA.

Second, imaging findings, such as bone marrow edema on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis, can be seen in asymptomatic, healthy individuals. In one study of 187 individuals aged 45 and younger, bone marrow edema and fat infiltration was seen on the MRI in 7% of healthy patients and 14% of patients, respectively. This study examined 75 patients with ankylosing spondylitis, 27 with pre-radiographic inflammatory back pain, 26 with nonspecific back pain and 59 healthy controls.3

Third, interpretation of imaging study results may vary among radiologists. Efforts to use data-driven definitions for active and structural lesions of the sacroiliac joints as evaluated by MRI are ongoing.

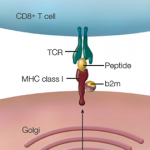

Pathogenesis: Dr. Deodhar noted that genetics, gut microbiome dysbiosis and entheseal trauma and inflammation likely all play a role in axSpA pathogenesis. The association between ankylosing spondylitis and HLA-B27 positivity has long been recognized. Work by Dr. Deodhar et al. has helped clarify how ankylosing spondylitis patients with this finding may differ from those who are negative for HLA-B27. Example: HLA-B27 negative ankylosing spondylitis is more prevalent in non-white patients. Those with non-radiographic axSpA experience a longer diagnostic delay and have a higher frequency of peripheral arthritis, dactylitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease. They also have less frequent radiographic sacroiliitis and less symmetry of syndesmophytes as compared with their HLA-B27 positive counterparts.4

Management Recommendations

With respect to evidence-based guidelines for the management of patients with axSpA, a number of international societies have written recommendations. But reconciling discrepancies between these documents can be challenging. Dr. Deodhar highlighted points of agreement among these international guidelines.

Overall, these points include managing ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axSpA in a similar manner. It also entails individualizing treatment based on patient-specific signs and symptoms, extra-articular manifestations and co-morbidities. Non-pharmacologic interventions include physical therapy, exercise, smoking cessation and management of psychosocial factors. For treatments, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be used as first-line interventions, and long-term systemic corticosteroids are discouraged. The first-line biologic agent should be a tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitor or interleukin (IL) 17 inhibitor. In general, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors should be used after failure of a TNF-α inhibitor.5,6

Patient Care

Dr. Deodhar concluded by discussing how rheumatologists can optimize quality of care in axSpA. One way is to individualize the treatment of the condition. Dr. Deodhar speculates that, in the future, this approach may include personalized medicine practices based on genetics, pharmacokinetics and other factors. He advises clinicians to routinely collect patient-reported outcomes and take these outcomes seriously when using a treat-to-target approach with patients. Focus on enhancing the multidisciplinary care of patients and the evaluation of potentially modifiable drivers of health-related quality of life. Also, it’s reasonable to explore tapering biologics with patients when it is appropriate to do so, but clinicians should avoid abruptly stopping medication completely.

When all actions on the part of the clinician seem to have failed, the rheumatologist should ask themselves several questions:

- Is the diagnosis correct?

- Is the disease still active, and am I treating inflammation or damage?

- Is the patient compliant with treatment?

- Are fibromyalgia, depression, sleep disturbance or different issues at play?

- Have I set realistic expectations for the patient in terms of anticipated results?

By running through this list of questions, the clinician can step back and gain a better understanding of the whole picture of the patient, thereby enabling holistic, more effective care of the patient as a person.

In Sum

The session provided by Dr. Deodhar was rich with insight, and the audience was left with many clinical pearls to help in the management of axSpA and non-radiographic axSpA.

Jason Liebowitz, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York.

References

- Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): Validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jun;68(6):777–783.

- Bohn R, Cooney M, Deodhar A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of axial spondyloarthritis: methodologic challenges and gaps in the literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018 Mar–Apr;36(2):263–274.

- Weber U, Lambert RG, Østergaard M, et al. The diagnostic utility of magnetic resonance imaging in spondyloarthritis: An international multicenter evaluation of one hundred eighty-seven subjects. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Oct;62(10):3048–3058.

- Deodhar A, Gill T, Magrey M. Human leukocyte antigen b27-negative axial spondyloarthritis: What do we know? ACR Open Rheumatol. 2023 Jul;5(7):333–344.

- Ramiro S, Nikiphorou E, Sepriano A, et al. ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):19–34.

- Hamilton L, Barkham N, Bhalla A, et al. BSR and BHPR guideline for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis (including ankylosing spondylitis) with biologics. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017 Feb;56(2):313–316.