Clinical Case

SG, a 49-year-old man, presented to the hospital with confusion, dysarthria, expressive aphasia, and progressive gait instability.

SG’s past medical history was remarkable only for congenital left hip dysplasia. He had been in his usual state of good health until four weeks prior to admission, when he experienced nasal congestion, pharyngitis, nausea, and intermittent vertigo. He also noted one episode of left arm pain followed by parasthesias and one episode of right leg paresthesias, both of which woke him from sleep and resolved spontaneously. He presented to an urgent care physician after two weeks of these symptoms and was prescribed meclizine for benign positional vertigo. He returned to his primary care physician the following day with the aforementioned symptoms, in addition to extreme fatigue, weakness, anorexia, and insomnia. He denied fevers, chills, and night sweats. His examination was reportedly unremarkable, other than cervical lymphadenopathy. He was diagnosed with a viral illness and Lyme serology was sent. There was no improvement in his symptoms over the subsequent week and he developed new waxing and waning confusion, word-finding difficulty, and progressively worsening gait instability. He had one episode of slurred speech. There were no descriptions of headache, tinnitus, hearing loss, or visual changes. At this point, he was brought to the hospital for further evaluation.

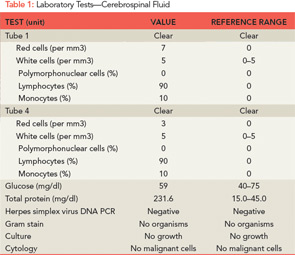

On arrival to an outside hospital emergency department, SG was arousable but unable to answer simple questions in an appropriate manner. Speech was repetitive and dysarthric, with expressive aphasia. He was able to follow simple commands. His physical examination was notable for right-sided nystagmus but was otherwise unremarkable. Gait was not assessed at that time. Routine laboratory tests were normal, and the prior test for Lyme disease was negative. A lumbar puncture was performed and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed high protein and low–normal glucose (see Table 1). Acyclovir and ceftriaxone were started empirically for infection. Magnetic resonance imaging and angiography (MRI/A) of the head and neck were performed. On fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery (FLAIR) imaging, a number of subcentimenter foci of increased T2 signal were seen within the periventricular white matter of both cerebral hemispheres and surrounding the fourth ventricle. A few lesions to the left of the corpus callosum were also seen. There was evidence of leptomeningeal enhancement. Magnetic resonance angiography of the circle of Willis revealed no significant areas of stenosis, aneurysm, or malformation.

SG was then transferred to our hospital for further evaluation. On arrival, he was afebrile and vital signs were normal. On neurologic examination, he was fully oriented, but was unable to relay his history due to word-finding difficulties, and speech was fragmented and circumferential in nature. He was able to recall zero out of three objects at five minutes. His cranial nerves were intact, but he had decreased hearing in the right ear. His reflexes were equal and intact. Mild dysmetria was observed with his left upper and lower extremities. His gait was unstable and he could not walk in tandem. His behavior was disinhibited and he expressed paranoid and delusional thoughts.