Editor’s note: In November, the ACR honored Joel M. Kremer, MD, MACR, president of the Corrona Research Foundation, with its Distinguished Clinical Investigator Award for his outstanding contributions to the field of rheumatology as a clinical scientist (see story here). As the founder of the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (CORRONA, now known as CorEvitas), Dr. Kremer made an indelible impact on how research is shared and real-world insights are gained. Here, he reflects on the genesis of the registry and what he learned along the way.

CORRONA’s Genesis

It’s the late 1990s. I’m a professor and division head at Albany Medical College (AMC), New York. We have a new head of the department of medicine who is a bottom-line guy. He would like me to expand my clinic time to nine, half-day sessions each week.

I like seeing patients but would certainly have liked another full day to focus on research. My research activities and family obligations with two young children had occupied all evenings and weekends for many years. There were overhead funds in college accounts from my studies of methotrexate (MTX), but I was informed these funds were insufficient to free up a day from clinic.

I loved what I was doing, including training fellows, residents and students. But, as we all know, money drives the academic bus. There is simply not enough overhead with clinical grants to buy back personal time to pursue other activities. I recognized that I needed to develop other sources of revenue if there was to be any prospect of opening my schedule.

At this time, there was an early report on the efficacy of etanercept. Would this new agent be the first of a new wave of so-called biologic agents with unique mechanisms of action? What if we could create an organization, a registry, to track the safety and effectiveness of new biologic agents in development as they entered the market? Short-term, randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) are one thing, but rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a lifelong disease. Inevitable channeling biases in who is included in RCTs also exist.

I reasoned that if an RA registry of these new agents could be created it might be possible to realize revenue while providing much-needed, real-world perspectives on long-term safety and effectiveness. I had no clue what would be involved in getting a registry started. But the idea did have some rather fortunate timely elements going for it.

First, my friends and colleagues doing clinical research at academic institutions around the country were (almost) as frustrated with their financial standing and academic perquisites as I was. This was important because if I was to ask for pharmaceutical industry (pharma) support for this initiative, conspicuous concerns would need to be addressed: What about other academic investigators in rheumatology? Are they also backing this effort? If not, then no deal. Big pharma would not risk antagonizing other high-profile academics to satisfy the goals of a single investigator.

This was going to be tricky. While my clinical investigator colleagues shared my frustrations, additional political realities had to be considered. Academic physicians are a competitive species. There will always be tensions among professionals sharing the same space. The dynamic balance of competition and collaboration is shaped by the landscape of opportunities at any given time. If the outcome of a collaborative effort is zero sum, then things can’t work. One member of a group cannot benefit at the expense of others. For academic collaborations to work, all participants must reap benefits.

Setting the Table

Toward the end of 1999 and through 2000–01, a series of face-to-face meetings was held with clinical academic colleagues from around the country. Prominent and established researchers would be needed to provide at least tacit support for the idea of a registry. We would meet in my hotel room at ACR national meetings, occupying bedsides and benches. People like Dan Furst, MD, Artie Kavanaugh, MD, Vibeke Strand, MD, Michael Weinblatt, MD, Lee Simon, MD, Bill Palmer, MD, Mike Schiff, MD, Alan Gibofsky, MD, JD, Jack Cush, MD, Stan Cohen, MD, and others were open to listening to ideas about a registry. If the initiative was successful, we could all be part of the novel accomplishment of the enterprise.

We also had to consider the rheumatologists who would be needed to complete questionnaires at the time of routine clinical encounters. No one was going to do the work of evaluating patients and completing forms without financial incentives.

We shopped the registry vision around to pharma, and we heard lots of nice comments about the good idea—and best wishes! It was apparent that achieving sufficient up-front funds to get a registry started was going to be a stretch. Any requested support had to be formulated and framed in a package that would be less stressful for pharma budgets and priorities.

What if pharma committed to pay in small increments only after patients

were enrolled?

We proposed an initial target enrollment of 300 patients. Achieving this modest enrollment would trigger an agreed-upon ka-ching, and then on to 500, 1,000, etc. This plan might overcome the reluctance of pharma to pay for a grand vision without a prior track record of success. Good ideas are one thing, but I had no experience. The reluctance to dedicate up-front funds to a new venture led by a doctor without bona fide business and organizational credentials was understandable.

An executive of a large French pharma company with whom I had collaborated on leflunomide research offered to cautiously provide limited support for modest initial enrollment numbers. This was an important breakthrough. It was now possible to approach other companies indicating that we already had support. Would they care to become part of this exciting nascent effort?

Early Model Fails

We moved ahead slowly with the model of payments for target enrollments achieved. After two years of planning, I enrolled CORRONA’s first patient in my AMC clinic in October 2001.

I had also approached the dean at AMC about the registry idea. Would he consider some up-front funding and then share in subsequent income? I was told this was clearly a hare-brained scheme. “Go see patients!” The no-nonsense rejection of this proposal would be a major factor in my subsequent decision to leave AMC. It wasn’t that I was insulted; I had expected to be rebuffed. But it had become apparent that if the registry concept was to be realized, it was not going to happen while I was at AMC.

It was also becoming clear that the initial model of payments for enrollments already achieved was not realistic. Personnel were needed to monitor site performance and rheumatologists expected to be financially incentivized to do the work of completing questionnaires. Imagine! And the questionnaires had to be developed, disseminated, collected and analyzed. The hole in the bottom of the barrel was getting bigger and bigger. Expenses and payments were out of sync. More funding had to come from somewhere. Soon!

I shared the dire financial realities with my clinical academic colleagues from around the country. We were running on fumes. There was always the hope that, with time, new biologic agents in development would expand our base of pharma companies willing to support the effort. Wishful thinking? Not uncommon in enterprises that eventually fail.

The CORRONA coordinator responsible for managing our small staff came to me in early 2004 with the news that insufficient funds were available to meet payroll the following week. I had been an academic doctor, although I had already transitioned to a hybrid private practice in which I continued to serve as the AMC fellowship director with rheumatology fellows, rotating residents and medical students in my clinic. My own personal financial resources were not flush after spending 20 years in academic medicine.

These moments of truth were coming in waves. Should I use my own limited resources to build a bridge to a time when other support might become available? Was this wise? Would I ever see a return on this potentially reckless, personal investment?

My wife, Sara, bravely agreed with the decision to tap into our own limited resources. She had been a witness to the passion and frustration that consumed this effort from the start.

Looking Up

Temporal trends with the introduction of new biologic agents supported the idea of a registry model for assessing the performance of expensive drugs with possible toxicities. Other pharmaceutical companies recognized that monitoring real-world performance of their drugs made sense. And of course, if long-term safety and effectiveness data were published on a competitor drug, then they would like to see publications on their drugs as well. Contracts were signed that were, at last, not directly dependent on enrollment numbers. We had a little more breathing room.

The infrastructure now included quality control, information technology (IT) and biostatistical support. We produced peer-reviewed publications. Site payments had to be improved! Changes in questionnaires, now needed on an annual basis as new drugs and toxicities were identified, could be daunting to sites.

The dedicated and superb CORRONA staff lead at this time, Kim Hinkle (now Kim Gottfried), BA, MS, knew the circumstances of each site and knew how to hold the hands of the physicians and research coordinators at our sites. Which clinical site coordinator was on maternity leave? Who was challenged with an especially cranky office manager? Who needed a special call? It was critical that site research personnel become true partners with CORRONA. They were rewarded with gift cards. But what always moved the collaborative needle was always the frequent and caring attention we paid to the dedicated research coordinators at CORRONA research sites. We initiated in-person and virtual meetings for them and paid them to attend. These people supplied us with practical guidance and advice on what might work and what wouldn’t.

Thus, CORRONA had to be on good terms with multiple constituents: physicians, site personnel, pharma executives and academic collaborators. CORRONA was exceptionally fortunate in that some very talented people were involved from the outset, including our superb chief biostatistician George Reed, PhD.

Jeff Greenberg, MD, MPH, was a young rheumatologist at New York University (NYU) who had been recommended to me. He had initially collaborated with CORRONA to fulfill the goals of a K award. Jeff recognized CORRONA’s potential with time and made the jump to a full-time employee in our fifth year. He has been an enormously valued contributor ever since.

Secret Sauce?

I have left out a key element without which the entire effort likely would have been stillborn: trust.

As noted, in these early years, CORRONA was challenged to pay physicians enough to make a substantial difference in their income. However, this was also a time when I was doing a series of frequent dinner talks with rheumatologists around the country. I would discuss my published research on MTX, as well as newly approved biologic agents. I had studied these drugs in my clinic and became a co-author on these high-profile publications. These research experiences informed my presentations to doctors around the country. I would always make it a point to feature CORRONA in my remarks as a much-needed means to determine how these drugs performed in the real world.

These rheumatologists and I belonged to the same band of brothers and sisters. I wasn’t some fast-talking, out-of-town salesman trying to sell the locals on a boondoggle in River City. It may sound self-serving, but it became apparent that I had a measure of credibility earned over decades of ACR presentations and publications on MTX, as well as the more recent publications on new biologic drugs. Jeff Greenberg would call this the secret sauce that encouraged participation—leadership from an individual whom doctors knew and trusted.

I very much honored that trust and also recognized a responsibility for open, honest and transparent communications.

A Fortunate Confluence of Circumstances

To review historical circumstances: I was a desperate clinical academic trying to create a different pathway to generate funds in order to free up time for research; there was an explosion of new and expensive drugs with their own novel safety concerns; there were the shared frustrations of other clinical academics who could participate in, and support, the vision; site physicians saw both the need for what the registry would provide and a measure of credibility of the messenger from decades of academic presentations and publications. It is a certainty the entire effort would have inevitably failed at multiple critical junctures without each and every one of these important elements.

The Rise of RISE

The ACR launches its own rheumatology registry

From the College

In 2014, Salahuddin Kazi, MD, then the chair of the ACR Registries and Health Information Technology Committee and program director of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, announced in the pages of The Rheumatologist the creation of the Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) registry, an enhanced version of the Rheumatology Clinical Registry (RCR).

Although RISE and CorEvitas are both registries, their objectives, goals and day-to-day functions differ greatly. First, CorEvitas’ foundational aims were safety focused, aiming to identify and analyze the safety and efficacy of therapeutics. In contrast, RISE was designed to provide quality improvement capabilities and federal quality reporting support for such programs as the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

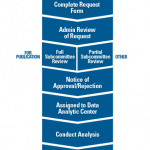

In addition to different goals, CorEvitas and RISE also have practical differences. RISE is electronic health record (EHR) enabled, meaning data collected during patient encounters are automatically extracted. CorEvitas relies on a case report form. Although that does necessitate additional forms for providers to complete and submit to the registry, participants receive a financial incentive to balance the burden of time spent.

The differences between EHR-enabled and case form-enabled registries go further. Because data from the EHR are automatically extracted for RISE, information on all diseases seen by rheumatology providers is collected. This is useful for providers who wish to track their performance on quality measures, expanding the usable measures.

Because CorEvitas relies on case forms, the data collected are more specific and limited. To accommodate the need to study various diseases, CorEvitas expanded by building additional disease-specific registries. In this way, CorEvitas serves more as an umbrella organization for these smaller registries.

By offering differing registry experiences and goals, both CorEvitas and RISE contribute important value to the medical community.

I never considered myself an entrepreneur, although I had been called that. In retrospect, it was fortunate for me that the administration at AMC had harshly disapproved the initiative, and that I chose to leave.

By 2011, nine-and-a-half years after the first patient was entered into the registry and almost 11 years after the idea was born, my wife and I were able to start to pay back our personal investment from years before. For the first time, I even started to take a modest salary from CORRONA. Prior to this juncture, every penny CORRONA generated went directly into facilitating the expansion of support personnel, infrastructure and site payments. A pure entrepreneur would have never made it through these long years without realizing income.

I was also a practicing rheumatologist. The academic colleagues who had supported the idea of a registry a decade before had become members of a CORRONA Board of Directors. They had been part of the struggle and were fully aware that no excess funds existed to be shared for almost a decade. These same individuals encouraged me to pay myself back from the earlier personal investment that had sustained the effort at a critical time.

During the many seasons of CORRONA growth, I frequently reasoned that if we could only make it through a given calendar year our long-term survival would likely be assured. This was wishful thinking. I learned that any endeavor requiring outside funding (and yes, CORRONA had to be managed with business principles) could only be sustained with black ink on balance sheets in the prior two quarters.

I read and digested management books (Note: Everything by Tom Peters is great), subscribed to and read valuable articles in the Harvard Business Review and tried to apply what I was learning to running CORRONA. (I have to say that I gained a newfound respect for what was needed to be successful in a business enterprise. I had always viewed business types—the suits—with a degree of disdain. But I learned that for any initiative requiring continued funding to survive and thrive, one needed diligence, creativity, vision and the willingness to take informed risks. Shooting from the hip was not a good business model.)

Expansion & More Challenges

The next years of CORRONA, now called CorEvitas, saw an expansion into 42 states with well over 150 sites enrolling patients and contributing data. We had become the largest rheumatology registry in the world. New European and Australian RA registries had been established in the first decades of this century. These registries were also sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry (with the exception of the independent, state-sponsored Swedish national ARTIS registry), starting up some years after CORRONA. The pharma-sponsored registry model had been embraced in different countries, although many country-specific differences in registry management and support existed.

And in 2014, the ACR launched the Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) registry (see sidebar, p. 57) to answer a need for quality reporting and quality improvement measures.

CORRONA could never rest on its laurels. Expansion of sites; the need for new and talented staff; refinement of clinical questionnaires, including new targeted adverse event forms; and strong IT and biostatistical support created relentless financial challenges.

It was becoming apparent in our 14th year that CORRONA would never be able to roll the big rock to the top of the hill without some additional infusion of capital. Things were never there and done in this rapidly changing therapeutic and practice environment. Many private sites now had considerable additional income associated with office infusions of biologic agents. CORRONA needed to sustain our model of attractive financial benefits in these changing circumstances.

We were approached by private equity (PE) companies that expressed some interest in investing in our model. They could supply much-needed capital while keeping experienced management in place. After much personal turmoil and angst, I agreed to a sale of CORRONA to PE. My metaphorical patient needed a transfusion, and I couldn’t pretend that things would be just fine without one. I became the chief medical officer of the new CORRONA, and Jeff Greenberg became the chief science officer.

Founding the Corrona Research Foundation

At the time of the transition to PE in mid-2014 I founded the Corrona Research Foundation, a not-for-profit 501(c)(3) organization. The foundation collaborates with talented academics from around the U.S. and Canada to develop and produce meaningful contributions to the medical literature by accessing the clinical data from CORRONA (now CorEvitas). The foundation functions without any profit requirement. I retired from seeing patients in July 2019 and remain engaged with the varied research efforts of the Corrona Research Foundation collaborating with talented academics throughout the country.

Joel M. Kremer, MD, MACR, has engaged in clinical research for the past four decades. He currently leads a not-for-profit research organization, the Corrona Research Foundation.