The diagnosis is confirmed by genetic testing, with most mutations present on exon 3 of the NLRP3 gene. More than 170 gene variants have been described. In some variations/mutations, a clear phenotype-genotype correlation exists. For example, the T348M mutation is associated with more severe hearing loss (as with the family in Case 2), but many mutations are not specific for a certain phenotype, such as the wide clinical spectrum seen in families with the E311K mutation.14,15 Therefore, it’s clear that the environment and, perhaps, epigenetics influence disease severity. Further, several variants (most commonly Q703K and V198M) are found in the general population (as much as 10% for Q703K), and their clinical significance is often not clear. Many patients with these variants exhibit nonspecific inflammatory symptoms.

Unfortunately, no mutations are found in many patients when tested by traditional methods, especially with those with NOMID/CINCA (40–50%) and MWS (25–33%).9 When tested (still not widely available in commercial testing) by massively parallel sequencing, somatic mosaicism (as opposed to germline mutations in which all cell lines are affected) is detected in nearly 70% of genetically negative NOMID/CINCA patients (in 4–36% of cells, perhaps with milder neurologic sequela), but only in 12.5% of MWS patients (in 5.5–35% of cells).16,17

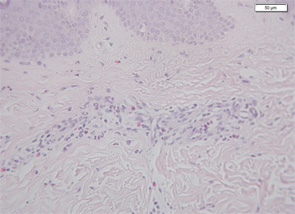

Therefore, a high level of suspicion and awareness is crucial in making the diagnosis of CAPS. There are several diagnostic aids to help diagnose these patients. These include a biopsy of the rash. Unlike classic urticaria, which is characterized by edema and the presence of mast cells, the rash in CAPS shows a dense neutrophilic infiltrate mainly in the lower (reticular) layer of the dermis, which tends to be perivascular and peri-eccrine (see Figure 5). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with a focus on the inner ear often shows edema with gadolinium enhancement (occasionally also meningeal enhancement is present) (see Figure 6). Lumbar puncture during attacks may show increased opening pressure with pleocytosis and elevated protein levels. Hearing tests showing high-frequency hearing loss may be a first sign of impending deafness. A detailed eye examination may reveal uveitis in addition to conjunctivitis. In unclear cases of FCAS, placing the patient in a very cold environment for 15–20 minutes may induce an attack and rash within 30 minutes to several hours, with increased production of acute-phase reactants.

Formal diagnostic criteria for CAPS have not yet been defined. In order not to deny treatment and prevent potentially devastating damage to patients, genetic confirmation should not be a compulsory criterion. In Table 2 (above), we suggest criteria for potential clinical diagnosis. Large databases, such as the Eurofever registry, may be an aid in defining evidence-based criteria.12