Over the past five decades, the treatment of lupus nephritis (LN) has evolved from a disease with high morbidity and mortality to one characterized by improved patient and renal survival. Despite these advances, cure remains elusive and its management fraught with unacceptable short and long term treatment-related side effects. What are the reasons for this current state? In this article, we summarize the history of LN treatment and present some explanations for the roadblocks to more effective therapies.

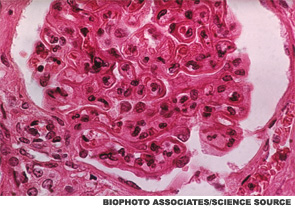

Class III/IV lupus nephritis remains one of the most serious manifestations of lupus, associated with the development of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), mortality and significant treatment-related side effects and organ damage, including avascular necrosis and premature ovarian failure. Both complete and partial remissions are associated with better overall renal and patient survival.1 The current goal in the treatment of Class III/IV LN is to induce remission with a combination of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, followed by a maintenance treatment phase of unclear duration incorporating little to no steroids along with an immunosuppressant.

Corticosteroids

In the early 1950s, Dubois et al reported on the use of corticosteroids in the treatment of 64 patients with active lupus, including patients with renal involvement; 30 patients were treated with various corticosteroid regimens, including ACTH, and 34 were untreated.2 Compared with untreated patients, corticosteroid use induced remission, provided a “Cushing state” was achieved. The 34 patients who were not treated with steroids all died from lupus. The authors reported that although there was no evidence that corticosteroids prolonged life expectancy at the time, steroid treatment induced remissions and concluded that “these agents are, at present, the most effective weapons available for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus.”

To this day, corticosteroids remain a standard, effective yet deleterious treatment for nearly all manifestations of lupus. Identifying safe and effective therapies that spare the use of steroids has been an important feature of clinical trials of therapeutics since.

Nitrogen Mustard

Dubois explored the use of nitrogen mustard for the treatment of 20 patients with lupus in 1954.3 Eleven patients had renal involvement, and eight of these patients demonstrated clinical improvement in terms of proteinuria and anasarca. Other publications, comprising small numbers of patients, also suggested that use of nitrogen mustard in addition to high-dose corticosteroids improved mortality rates in patients with less severe renal involvement.4

Immunosuppressive Agent + Steroids

In the 1970s and 1980s, results of the NIH cyclophosphamide protocol evolved under the leadership of John Decker, MD, demonstrating five-year renal survival rates of 60–80%.5 At this time, the benefits of the addition of an immunosuppressive agent to background steroids remained controversial, with some investigators arguing that the addition of potent immunosuppressive therapies was not supported by results from small clinical trials of patients with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis.6,7